From inside the car, I watched as parents gingerly stepped out of the high-rise lobby, kids in tow, trying to get to school and out of the unforgiving lake wind. A crossing guard motioned them to hurry up and cross the street, for there were a couple of eighteen-wheelers idling impatiently at a green light. As they passed his car, J.T. waved. Our breath was fogging up the windshield. He turned on the defroster, jacked the music a bit louder. “One day,” he said. “Take it or leave it. That’s all I’m saying. One day.”

I met J.T. at seven-thirty the next morning at Kevin’s Hamburger Heaven in Bridgeport, a predominantly Irish-American neighborhood across the expressway from the projects. This was his regular morning spot. “None of these white folks here know me,” he said, “so I don’t get any funny looks.”

His steak and eggs arrived just as I sat down. He always ate alone, he said. Soon enough he’d be joined by two of his officers, Price and T-Bone. Even though J.T.’s gang was nearly twice as large as most others on the South Side, he kept his officer class small, because he trusted very few people. All of his officers were friends he’d known since high school.

“All right,” he began, “let’s talk a little about-”

“Listen,” I blurted out, “I can’t kill anybody, I can’t sell shit to anybody.” I had been awake much of the night worrying. “Or even plan any of that stuff! Not me!”

“Okay, nigger, first of all you need to stop shouting.” He looked about the room. “And stop worrying. But let me tell you what I’m worried about, chief.”

He twirled a piece of steak on his fork as he dabbed his mouth with a napkin.

“I can’t let you do everything, right, because I’ll get into trouble, you dig? So there’s just going to be some stuff you can’t do. And you already told me some of the other stuff you don’t want to be doing. But all that doesn’t matter, because I got plenty of stuff to keep you busy for the day. And only the cats coming for breakfast know what you’ll be doing. So don’t be acting like you run the place in front of everybody. Don’t embarrass me.”

It was his own bosses, J.T. explained, that he was worried about, the Black Kings’ board of directors. The board, roughly two dozen men who controlled all the neighborhood BK gangs in Chicago, kept a close eye on drug revenues, since their generous skim came off the top. They were always concerned that local leaders like J.T. keep their troops in line. Young gang members who made trouble drew unwanted police attention, which made it harder to sell drugs; the fewer drugs that were sold, the less money the board collected. So the board was constantly reminding J.T. to minimize the friction of his operation.

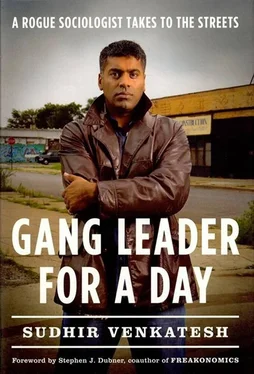

As J.T. was explaining all this, he repeated that only his senior officers knew that I was gang leader for a day. It wouldn’t do, he said, for the gang’s rank and file to learn of our experiment, nor the community at large. I was excited at the thought of spending the day with J.T. I felt he might not be able to censor what I saw if I was with him for a full day. It was also an obvious sign that he trusted me. And I think he was flattered that I was interested in knowing what actually went into his work.

Impatient, I asked him what my first assignment was.

“You’ll find out in a minute, as soon as I do. Eat up, you’re going to need it.”

I was nervous, to be sure, but not because I was implicating myself in an illegal enterprise. In fact, I hadn’t even really thought about that angle. I probably should have. At most universities, faculty members solicit approval for their research from institutional review boards, which act as the main insurance against exploitative or unethical research. But the work of graduate students is largely overlooked. Only later, when I began sharing my experiences with my advisers and showing them my field notes, did I begin to understand-and adhere to-the reporting requirements for researchers who are privy to criminal conduct. But at the time, with little understanding of these protocols, I simply relied on my own moral compass.

This compass wasn’t necessarily reliable. To be honest, I was a bit overwhelmed by the thrill of further entering J.T.’s world. I hoped he would someday introduce me to the powerful Black Kings leadership, the reputedly ruthless inner-city gang lords who had since transplanted themselves to the Chicago suburbs. I wondered if they were some kind of revolutionary vanguard, debating the theories of Karl Marx and W. E. B. Du Bois, Frantz Fanon and Kwame Nkrumah. (Probably not.) I also hoped that J.T. would bring me to some dark downtown tavern where large Italian men in large Italian suits met with black hustlers like J.T. to dream up a multiethnic, multigenerational,multimillion-dollar criminal plan. My mind, it was safe to say, was racing out of control.

Price and T-Bone soon arrived and sat down at our table. By now I knew these two pretty well-T-Bone, the gang’s bookish and chatty treasurer (which meant he handled most of the gang’s fiscal and organizational issues), and Price, the thuggish and hard-living security chief (a job that included the allocation of particular street corners to particular BK dealers). They were the two men most responsible for helping J.T. with day-to-day affairs. They both nodded in my direction as they sat down, then looked toward J.T.

“Okay, T-Bone,” J.T. said, “you’re up, nigger. Talk to me. What’s happening today?”

“Whoa, whoa!” I said. “I’m in charge here, no? I should call this meeting to order, no?”

“Okay, nigger,” J.T. said, again glancing around. He still seemed concerned that I was talking too loud. “Just be cool.”

I tried to calm down. “T-Bone, you’re up. Talk to me, nigger.”

J.T. collapsed on the table, laughing hard. T-Bone and Price laughed along with him.

“If he calls me ‘nigger’ again, I’m giving him an ass whupping,” T-Bone said. “I don’t care if he’s my leader.”

J.T. told T-Bone to go ahead and start listing the day’s tasks.

“Ms. Bailey needs about a dozen guys to clean up the building today,” T-Bone said. “Last night Josie and them partied all night long, and there’s shit everywhere. We need to send guys to her by eleven or she will be pissed. And I do not want to be dealing with her when she’s pissed. Not me.”

“Okay, Sudhir,” J.T. said, “what do we do?” He folded his arms and sat back, as if he’d just set up a checkmate.

“What? Are you kidding me? Is this a joke?”

“Ain’t no joke,” said T-Bone flatly. “What do I do?” He looked at J.T., who pointed his finger at me. “C’mon, chief,” T-Bone said to me. “I got about ten things I need to go over. Let’s do this.”

J.T. explained that he had to keep Ms. Bailey happy, since the gang sold crack in the lobby of her building and as building president she had the power to make things difficult. To appease her, J.T. regularly assigned his members to clean up her building and do other menial jobs. The young drug dealers hated these assignments not only because they were humiliating but because every hour of community service was one less hour earning money. Josie was a teenage member of J.T.’s gang who’d apparently thrown a party with some prostitutes and left the stairwells and gallery strewn with broken glass, trash, and used condoms.

“All right, who hasn’t done cleanup in a while?” I asked.

“Well, you have Moochie’s group and Kalia’s group,” T-Bone said. “Both of them ain’t cleaned up for about three months.” Moochie and Kalia were each in charge of a six-member sales force.

“Okay, how do we make a decision between the two?” I asked.

“Well, it depends on what you think is important,” J.T. said. “Moochie’s been making tall money, so you may not want to pull him off the streets. Kalia ain’t been doing so hot lately, so maybe you want him to clean up, ’cause he isn’t bringing in money anyway.”

Читать дальше