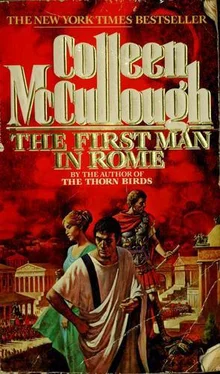

Colleen McCullough - 1. First Man in Rome

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Colleen McCullough - 1. First Man in Rome» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Современная проза. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:1. First Man in Rome

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

1. First Man in Rome: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «1. First Man in Rome»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

1. First Man in Rome — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «1. First Man in Rome», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

But the wheel, thought Gaius Marius as he climbed out of his bath and picked up a towel to dry himself, turns full circle no matter what we do. Spite from the mouth of a half-grown sprig of a most noble house was no less true for being spiteful. Who were they in actual fact, the Terrible Trio of Numantia? Why, they were a greasy foreigner, a jumped-up favor currier, and an Italian hayseed with no Greek. That's who they were. Rome had taught them the truth of it, all right. Jugurtha should have been acknowledged King of Numidia years ago, brought firmly yet kindly into the Roman fold of client-kings, kept there with sound advice and fair dealing. Instead, he had suffered the implacable enmity of the entire Caecilius Metellus faction, and was currently in Rome with his back against the wall, fighting a last-ditch stand against a group of Numidian would-be kings, forced to buy what his worth and his ability ought to have earned him free and aboveboard. And dear little sandy-headed Publius Rutilius Rufus, the favorite pupil of Panaetius the philosopher, admired by the whole of the Scipionic Circle writer, soldier, wit, politician of extraordinary excellence had been cheated of his consulship in the same year Marius had barely managed a praetorship. Not only was Rutilius's background not good enough, he had also incurred the enmity of the Caecilius Metelluses, and that meant he like Jugurtha automatically became an enemy of Marcus Aemilius Scaurus, closely allied to the Caecilius Metelluses. and chief glory of their faction. As for Gaius Marius well, as Quintus Caecilius Metellus Piggle-wiggle would say, he had done better than any Italian hayseed with no Greek should. Why had he ever decided to go to Rome and try the political ladder anyway? Simple. Because Scipio Aemilianus (like most of the highest patricians, Scipio Aemilianus was no snob) thought he must. He was too good a man to waste filling a country squire's shoes, Scipio Aemilianus had said. Even more important, if he didn't become a praetor, he could never command an army of Rome. So Marius had stood for election as a tribune of the soldiers, got in easily, then stood for election as a quaestor, was approved by the censors and found himself, an Italian hayseed with no Greek, a member of the Senate of Rome. How amazing that had been! How stunned his family back in Arpinum! He'd done his share of time serving and managed to scramble a little way upward. Oddly enough, it had been Caecilius Metellus support which had then secured him election as a tribune of the plebs in the severely reactionary time which had followed immediately after the death of Gaius Gracchus. When Marius had first sought election to the College of Tribunes of the Plebs, he hadn't got in; the year he did get in, the Caecilius Metellus faction was convinced it owned him. Until he showed it otherwise by acting vigorously to preserve the freedom of the Plebeian Assembly, never more threatened with being overpowered by the Senate than after the death of Gaius Gracchus. Lucius Caecilius Metellus Dalmaticus tried to push a law through that would have curtailed the ability of the Plebeian Assembly to legislate, and Gaius Marius vetoed it. Nor could Gaius Marius be cajoled, coaxed, or coerced into withdrawing his veto. But that veto had cost him dearly. After his year as a tribune of the plebs, he tried to run for one of the two plebeian aedile magistracies, only to be foiled by the Caecilius Metellus lobby. So he had campaigned strenuously for the praetorship, and encountered Caecilius Metellus opposition yet again. Led by Metellus Dalmaticus, they had employed the usual kind of defamation he was impotent, he molested little boys, he ate excrement, he belonged to secret societies of Bacchic and Orphic vice, he accepted every kind of bribe, he slept with his sister and his mother. But they had also employed a more insidious form of defamation more effectively; they simply said that Gaius Marius was not a Roman, that Gaius Marius was an upcountry Italian nobody, and that Rome could produce more than enough true sons of Rome to make it unnecessary for any Roman to elect a Gaius Marius to the praetorship. It was a telling point. Minor criticism though it was compared to the rest, the most galling calumny of all as far as Gaius Marius was concerned was the perpetual inference that he was unacceptably crass because he had no Greek. The slur wasn't true; he spoke very good Greek. However, his tutors had been Asian Greeks his pedagogue hailed from Lampsacus on the Hellespont, and his grammaticus from Amisus on the coast of Pontus and they spoke a heavily accented Greek. Thus Gaius Marius had learned Greek with a twang to it that branded him improperly taught as a common, underbred sort of fellow. He had been obliged to acknowledge himself defeated; if he said no Greek at all or if he said miles of Asian Greek, it came to the same thing. In consequence he ignored the slander by refusing to speak the language which indicated that a man was properly educated and cultured. Never mind. He had scraped in last among the praetors, but he had scraped in nonetheless. And survived a trumped-up charge of bribery brought against him just after the election. Bribery! As if he could have! No, in those days he hadn't had the kind of money necessary to buy a magistracy. But luckily there were among the electors enough men who either knew firsthand of his soldierly valor, or had heard about it from those who did. The Roman electorate always had a soft spot for an excellent soldier, and it was that soft spot which won for him. The Senate had posted him to Further Spain as its governor, thinking he'd be out of sight, out of mind, and perhaps handy. But since he was a quintessential Military Man, he thrived.

* * *

The Spaniards especially the half-tamed tribes of the Lusitanian west and the Cantabrian northwest excelled in a kind of warfare that didn't suit most Roman commanders any more than it suited the style of the Roman legions. Spaniards never deployed for battle in the traditional way, cared nothing for the universally accepted tenet that it was better to gamble everything you had on the off chance of winning a decisive battle than to incur the horrific costs of a prolonged war. The Spaniards already understood that they were fighting a prolonged war, a war which they had to continue so long as they desired to preserve their Celtiberian identity; as far as they were concerned, they were engaged in an ongoing struggle for social and cultural independence. But, since they certainly didn't have the money to fight a prolonged war, they fought a civilian war. They never gave battle. Instead, they fought by ambush, raid, assassination, and devastation of all Enemy property. That is, Roman property. Never appearing where they were expected, never marching in column, never banding together in any numbers, never identifiable by the wearing of uniforms or the carrying of arms. They just pounced. Out of nowhere. And then vanished without a trace into the formidable crags of their mountains as if they had never been. Ride in to inspect a small town which Roman intelligence positively stated was involved in some clever minor massacre, and it would be as idle, as innocent, as unimpeachable as the most docile and patient of asses. A fabulously rich land, Spain. As a result, everyone had had a go at owning it. The original Iberian indigenes had been intermingling with Celtic elements invading across the Pyrenees for a thousand years, and Berber-Moor incursions from the African side of the narrow straits separating Spain from Africa had further enriched the local melting pot. Then a thousand years ago came the Phoenicians from Tyre and Sidon and Berytus on the Syrian coast, and after them came the Greeks. Two hundred years ago had come the Punic Carthaginians, themselves descendants of the Syrian Phoenicians who had founded an empire based on African Carthage; and the relative isolation of Spain was finished. For the Carthaginians came to Spain to mine its metals. Gold, silver, lead, zinc, copper, and iron. The Spanish mountains were loaded with all of them, and everywhere in the world the demand for goods made out of some and wealth made out of others was rapidly increasing. Punic power was based upon Spanish ore. Even tin came from Spain, though it wasn't found there; mined in the fabled Cassiterides, the Tin Isles somewhere at the ultimate limit of the livable globe, it arrived in Spain through little Cantabrian ports and traveled the Spanish trade routes down to the shores of the Middle Sea. The seagoing Carthaginians had owned Sicily, Sardinia, and Corsica too, which meant that sooner or later they had to run foul of Rome, a fate that had overtaken them 150 years before. And three wars later three wars which took over a hundred years to fight Carthage was dead, and Rome had acquired the first of its overseas possessions. Including the mines of Spain. Roman practicality had seen at once that Spain was best governed from two different locations; the peninsula was divided into the two provinces of Nearer Spain Hispania Citerior and Further Spain Hispania Ulterior. The governor of Further Spain controlled all the south and west of the country from a base in the fabulously fertile hinterlands of the Baetis River, with the mighty old Phoenician city of Gades near its mouth. The governor of Nearer Spain controlled all the north and east of the peninsula from a base in the coastal plain opposite the Balearic Isles, and shifted his capital around as the whim or the need dictated. The lands of the far west Lusitania and the lands of the northwest Cantabria remained largely untouched. Despite the object lesson Scipio Aemilianus had made out of Numantia, the tribes of Spain continued to resist Roman occupation by ambush, raid, assassination, and devastation of property. Well now, thought Gaius Marius, coming on this most interesting scene when he arrived in Further Spain as its new governor, I too can fight by ambush, raid, assassination, and devastation of property! And proceeded to do so. With great success. Out thrust the frontiers of Roman Spain into Lusitania and the mighty chain of ore-bearing mountains in which rose the Baetis, Anas, and Tagus rivers. It was really not an exaggeration to say that as the Roman frontier advanced, the Roman conquerors kept tripping over richer and richer deposits of ore, especially silver, copper, and iron. And naturally the governor of the province he who achieved the new frontiers in the name of Rome was in the forefront of those who acquired grants of ore-bearing land. The Treasury of Rome took its cut, but preferred to leave the mine owning and actual mining in the hands of private individuals, who did it far more efficiently and with a more consistent brand of exploitative ruthlessness. Gaius Marius got rich. Then got richer. Every new mine was either wholly or partly his; this in turn brought him sleeping partnerships in the great companies which contracted out their services to run all kinds of commercial operations from grain buying and selling and shipping, to merchant banking and public works all over the Roman world, as well as within the city of Rome itself. He came back from Spain having been voted imperator by his troops, which meant that he was entitled to apply to the Senate for permission to hold a triumph; considering the amount of booty and tithes and taxes and tributes he had added to the general revenues, the Senate could not do else than comply with the wishes of his soldiers. And so he drove the antique triumphal chariot along its traditional route in the triumphal parade, preceded by the heaped-up evidence of his victories and depredations, the floats depicting tableaux and geography and weird tribal costumes; and dreamed of being consul in two years' time. He, Gaius Marius from Arpinum, the despised Italian hayseed with no Greek, would be consul of the greatest city in the world. And go back to Spain and complete its conquest, turn it into a peaceful, prosperous pair of indisputably Roman provinces. But it was five years since he had returned to Rome. Five years! The Caecilius Metellus faction had finally won: he would never be consul now.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «1. First Man in Rome»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «1. First Man in Rome» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «1. First Man in Rome» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.