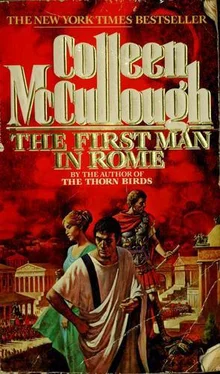

Colleen McCullough - 1. First Man in Rome

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Colleen McCullough - 1. First Man in Rome» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Современная проза. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:1. First Man in Rome

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

1. First Man in Rome: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «1. First Man in Rome»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

1. First Man in Rome — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «1. First Man in Rome», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

"I think I'll wear the Chian outfit," he said to his body servant, standing waiting for orders. Many men in Marius's position would have lain back in the bath water and demanded that they be scrubbed, scraped, and massaged by slaves, but Gaius Marius preferred to do his own dirty work, even now. Mind you, at forty-seven he was still a fine figure of a man. Nothing to be ashamed of about his physique! No matter how ostensibly inert his days might be, he got in a fair amount of exercise, worked with the dumbbells and the closhes, swam if he could several times across the Tiber in the reach called the Trigarium, then ran all the way back from the far perimeter of the Campus Martius to his house on the flanks of the Capitoline Arx. His hair was getting a bit thin on top, but he still had enough dark brown curls to brush forward into a respectable coiffure. There. That would have to do. A beauty he never had been, never would be. A good face even an impressive one but no rival for Gaius Julius Caesar's! Interesting. Why was he going to so much trouble with hair and dress for what promised to be a small family meal in the dining room of a modest backbencher senator? A man who hadn't even been aedile, let alone praetor. The Chian outfit he had elected to wear, no less! He had bought it several years ago, dreaming of the dinner parties he would host during his consulship and the years thereafter when he would be one of the esteemed ex-consuls, the consulars as they were called. It was permissible to attire oneself for a purely private dinner party in less austere clothes than white toga and tunic, a bit of purple stripe their only decoration; and the Chian tapestry tunic with long drape to go over it was a spectacle of gold and purple lavishness. Luckily there were no sumptuary laws on the books at the moment that forbade a man to robe himself as ornately and luxuriously as he pleased. There was only a lex Licinia, which regulated the amount of expensive culinary rarities a man might put on his table and no one took any notice of that. Besides which, Gaius Marius doubted that Caesar's table would be loaded down with licker-fish and oysters.

Not for one moment did it occur to Gaius Marius to seek out his wife before he departed. He had forgotten her years ago if, in fact, he ever had remembered her. The marriage had been arranged during the sexless limbo of childhood and had lingered in the sexless limbo of an adult lack of love or even affinity for twenty-five childless years. A man as martially inclined and physically active as Gaius Marius sought sexual solace only when its absence was recollected by a chance encounter with some attractive woman, and his life had not been distinguished by many such. From time to time he enjoyed a mild fling with the attractive woman who had taken his eye (if she was available and willing), or a house girl, or (on campaign) a captive girl. But Grania, his wife? Her he had forgotten, even when she was there not two feet from him, reminding him that she would like to be slept with often enough to conceive a child. Cohabitating with Grania was like leading a route march through an impenetrable fog. What you felt was so amorphous it kept squeezing itself into something different yet equally unidentifiable; occasionally you were aware of a change in the ambient temperature, patches of extra moistness in a generally clammy substrate. By the time his climax arrived, if he opened his mouth at all it was to yawn. He didn't pity Grania in the least. Nor did he attempt to understand her. Simply, she was his wife, his old boiling fowl who had never worn the plumage of a spring chicken, even in her youth. What she did with her days or nights he didn't know, didn't worry about. Grania, leading a double life of licentious depravity? If someone had suggested to him that she might, he would have laughed until the tears came. And he would have been quite right to do so. Grania was as chaste as she was drab. No Caecilia Metella (the wanton one who was sister to Dalmaticus and Metellus Piggle-wiggle, and wife to Lucius Licinius Lucullus) about Grania from Puteoli! His silver mines had bought the house high on the Arx of the Capitol just on the Campus Martius side of the Servian Walls, the most expensive real estate in Rome; his copper mines had bought the colored marbles with which its brick-and-concrete columns and divisions and floors were sheathed; his iron mines had bought the services of the finest mural painter in Rome to fill up the plastered spaces between pilasters and divisions with scenes of stag hunts and flower gardens and trompe l'oeil landscapes; his sleeping partnerships in several large companies had bought the statues and the herms, the fabulous citrus-wood tables on their gold-inlaid ivory pedestals, the gilded and encrusted couches and chairs, the gloriously embroidered hangings, the cast-bronze doors; Hymettus himself had landscaped the massive peristyle-garden, paying as much attention to the subtle combination of perfumes as he did to the colors of the blossoms; and the great Dolichus had created the long central pool with its fountains and fish and lilies and lotuses and superb larger-than-life sculptures of tritons, nereids, nymphs, dolphins, and bewhiskered sea serpents. All of which, truth to tell, Gaius Marius did not give tuppence about. The obligatory show, nothing else. He slept on a camp bed in the smallest, barest room of the house, its only hangings his sword and scabbard on one wall and his smelly old military cape on another, its only splash of color the rather grimy and tattered vexillum flag his favorite legion had given him when their campaign in Spain was over. Ah, that was the life for a man! The only true value praetorship and consulship had for Gaius Marius was the fact that both led to military command of the highest order. But consul far more than praetor! And he knew he would never be consul, not now. They wouldn't vote for a nobody, no matter how rich he might be.

He walked in the same kind of weather the previous day had endured, a dreary mizzling rain and an all-pervading dampness, forgetting which was quite typical that he had a fortune on his back. However, he had thrown his old campaigning sagum over his finery a thick, greasy, malodorous cape which could keep out the perishing winds of the alpine passes or the soaking days-long downpours of Epirus. The sort of garment a soldier needed. Its reek stole into his nostrils like a trickle of vapor from a bakery, hunger making, voluptuous on the gut, warmly friendly. "Come in, come in!" said Gaius Julius Caesar, welcoming his guest in person at the door, and holding out his own finely made hands to receive the awful sagum. But having taken it, he didn't immediately toss it to the waiting slave as if afraid its smell might cling to his skin; instead, he fingered it with respect before handing it over carefully. "I'd say that's seen a few campaigns," he said then, not blinking an eye at the sight of Gaius Marius in all the vulgar ostentation of a gold-and-purple Chian outfit. "It's the only sagum I've ever owned," said Gaius Marius, oblivious to the fact that his Chian tapestry drape had flopped itself all the wrong way. "Ligurian?" "Of course. My father gave it to me brand-new when I turned seventeen and went off to do my service as a cadet. But I tell you what," Gaius Marius went on, not noticing the smallness and simplicity of the Gaius Julius Caesar house as he strolled beside his host to the dining room, "when it came my turn to equip and outfit legions, I made sure my men all got the exact same cape no use expecting men to stay healthy if they're wet through or chilled to the bone." He thought of something important, and added hastily, "Of course I didn't charge 'em more than the standard military-issue price! Any commander worth his salt ought to be able to absorb the extra cost from extra booty." "And you're worth your salt, I know," said Caesar as he sat on the edge of the middle couch at its left-hand end, indicating to his guest that he take the place to the right, which was the place of honor. Servants removed their shoes, and, when Gaius Marius declined to suffer the fumes of a brazier, offered socks; both men accepted, then arranged their angle of recline by adjusting the bolsters supporting their left elbows into comfortable position. The wine steward stepped forward, attended by a cup bearer. "My sons will be in shortly, and the ladies just before we eat," said Caesar, holding his hand up to arrest the progress of the wine steward. "I hope, Gaius Marius, that you won't deem me a niggard with my wine if I respectfully ask you to take it as I intend to myself, well watered? I do have a valid reason, but it is one I do not believe can be explained away so early. Simply, the only reason I can offer you right now is that it behooves both of us to remain in full possession of our wits. Besides, the ladies become uneasy when they see their men drinking unwatered wine." "Wine bibbing isn't one of my failings," said Gaius Marius, relaxing and cutting the wine pourer impressively short, then ensuring that his cup was filled almost to its brim with water. "If a man cares enough for his company to accept an invitation to dinner, then his tongue should be used for talking rather than lapping." "Well said!" cried Caesar, beaming. "However, I am mightily intrigued!" "In the fullness of time, you shall know it all." A silence fell. Both men sipped at their wine-flavored water a trifle uneasily. Since they knew each other only from nodding in passing, one senator to another, this initial bid to establish a friendship could not help but be difficult. Especially since the host had put an embargo upon the one thing which would have made them more quickly comfortable wine. Caesar cleared his throat, put his cup down on the narrow table which ran just below the inside edge of the couch. "I gather, Gaius Marius, that you are not enthused about this year's crop of magistrates," he said. "Ye gods, no! Any more than you are, I think." "They're a poor lot, all right. Sometimes I wonder if we are wrong to insist that the magistracies last only one year. Perhaps when we're lucky enough to get a really good man in an office, we should leave him there longer to get more done." "A temptation, and if men weren't men, it might work," said Marius. "But there is an impediment." "An impediment?" "Whose word are we going to take that a good man is a good man? His? The Senate's? The People's Assemblies'? The knights'? The voters', incorruptible fellows that they are, impervious to bribes?" Caesar laughed. "Well, I thought Gaius Gracchus was a good man. When he ran for his second term as a tribune of the plebs I supported him wholeheartedly and I supported his third attempt too. Not that my support could count for much, my being patrician." "And there you have it, Gaius Julius," said Marius somberly. "Whenever Rome does manage to produce a good man, he's cut down. And why is he cut down? Because he cares more for Rome than he does for family, faction, and finances." "I don't think that's particularly confined to Romans," said Caesar, raising his delicate eyebrows until his forehead rippled. "People are people. I see very little difference between Romans, Greeks, Carthaginians, Syrians, or any others you care to name, at least when it comes to envy or greed. The only possible way the best man for the job can keep it long enough to accomplish what his potential suggests he can accomplish is to become a king. In fact, if not in name." "And Rome would never condone a king," said Marius. "It hasn't for the last five hundred years. We grew out of kings. Odd, isn't it? Most of the world prefers absolute rule. But not we Romans. Nor the Greeks, for that matter." Marius grinned. "That's because Rome and Greece are stuffed with men who consider they're all kings. And Rome certainly didn't become a true democracy when we threw our kings out." "Of course not! True democracy is a Greek philosophic unattainable. Look at the mess the Greeks made of it, so what chance do we sensible Roman fellows stand? Rome is government of the many by the few. The Famous Families." Caesar dropped the statement casually. "And an occasional New Man," said Gaius Marius, New Man. "And an occasional New Man," agreed Caesar placidly. The two sons of the Caesar household entered the dining room exactly as young men should, manly yet deferential, restrained rather than shy, not putting themselves forward, but not holding themselves back. Sextus Julius Caesar was the elder, twenty-five this year, tall and tawny-bronze of hair, grey of eye. Used to assessing young men, Gaius Marius detected an odd shadow in him: there was the faintest tinge of exhaustion in the skin beneath his eyes, and his mouth was tight-lipped yet not of the right form to be tight-lipped. Gaius Julius Caesar Junior, twenty-two this year, was sturdier than his brother and even taller, a golden-blond fellow with bright blue eyes. Highly intelligent, thought Marius, yet not a forceful or opinionated young man. Together they were as handsome, Roman-featured, finely set-up a pair of sons as any Roman senator father might hope to sire. Senators of tomorrow. "You're fortunate in your sons, Gaius Julius," Marius said as the young men disposed themselves on the couch standing at right angles to their father's right; unless more guests were expected (or this was one of those scandalously progressive houses where the women lay down to dine), the third couch, at right angles to Marius's left, would remain vacant. "Yes, I think I'm fortunate," said Caesar, smiling at his sons with as much respect as love in his eyes. Then he turned on his elbow to look at Gaius Marius, his expression changing to a courteous curiosity. "You don't have any sons, do you?" "No," said Marius unregretfully. "But you are married?" "I believe so!" said Marius, and laughed. "We're all alike, we military men. Our real wife is the army." "That happens," said Caesar, and changed the subject. The predinner talk was cultivated, good-tempered, and very considerate, Marius noticed; no one in this house needed to put down anyone else who lived here, everyone stood upon excellent terms with everyone else, no latent discord rumbled an undertone. He became curious to see what the women were like, for the father after all was only one half of the source of this felicitous result; espoused to a Puteolan pudding though he was, Marius was no fool, and he personally knew of no wife of the Roman nobility who didn't have a large input to make when it came to the rearing of her children. No matter whether she was profligate or prude, idiot or intellectual, she was always a person to be reckoned with. Then they came in, the women. Marcia and the two Julias. Ravishing! Absolutely ravishing, including the mother. The servants set upright chairs for them inside the hollow center of the U formed by the three dining couches and their narrow tables, so that Marcia sat opposite her husband, Julia sat facing Gaius Marius, and Julilla sat facing her two brothers. When she knew her parents weren't looking at her but the guest was, Julilla stuck out her tongue at her brothers, Marius noted with amusement. Despite the absence of licker-fish and oysters and the presence of heavily watered wine, it was a delightful dinner served by unobtrusive, contented-looking slaves who never shoved rudely between the women and the tables, nor neglected a duty. The food was plain but excellently cooked, the natural flavors of meats, fruits, and vegetables undisguised by fishy garum essences and bizarre mixtures of exotic spices from the East; it was, in fact, the kind of food the soldier Marius liked best. Roast birds stuffed with simple blends of bread and onions and green herbs from the garden, the lightest of fresh-baked rolls, two kinds of olives, dumplings made of delicate spelt flour cooked with eggs and cheese, deliciously country-tasting sausages grilled over a brazier and basted with a thin coat of garlic and diluted honey, two excellent salads of lettuces, cucumbers, shallots, and celery (each with a differently flavored oil-and-vinegar dressing), and a wonderful lightly steamed medley of broccoli, baby squash, and cauliflower dashed over with oil and grated chestnut. The olive oil was sweet and of the first pressing, the salt dry, and the pepper of the best quality was kept whole until one of the diners signaled the lad who was its custodian to grind up a pinch in his mortar with his pestle, please. The meal finished with little fruit tarts, some sticky squares of sesame seed glued together with wild thyme honey, pastry envelopes filled with raisin mince and soaked in syrup of figs, and two splendid cheeses. "Arpinum!" exclaimed Marius, holding up a wedge of the second cheese, his face with its preposterous eyebrows suddenly seeming years younger. "I know this cheese well! My father makes it. The milk is from two-year-old ewes, and taken only after they've grazed on the river meadow for a week, where the special milkgrass grows." "Oh, how nice," said Marcia, smiling at him without a trace of affectation or selfconsciousness. "I've always been fond of this particular cheese, but from now on I shall look out for it especially. The cheese made by Gaius Marius your father is also a Gaius Marius? of Arpinum." The moment the last course was cleared away the women rose to take their leave, having had no sip of wine, but dined heartily on the food and drunk deeply of the water. As she got up Julia smiled at him with what seemed genuine liking, Marius noted; she had made polite conversation with him whenever he initiated it, but made no attempt to turn the discourse between him and her father into a three-sided affair. Yet she hadn't looked bored, but had followed what Caesar and Marius talked about with evident interest and understanding. A truly lovely girl, a peaceful girl who yet did not seem destined to turn into a pudding. Her little sister, Julilla, was a scamp delightful, yes, but a regular handful too, suspected Marius. Spoiled and willful and fully aware of how to manipulate her family to get her own way. But there was something in her more disquieting; the assessor of young men was also a fairly shrewd assessor of young women. And Julilla caused his hackles to ripple ever so softly and slightly; somewhere in her was a defect, Marius was sure. Not exactly lack of intelligence, though she was less well read than her elder sister and her brothers, and clearly not a whit perturbed by her ignorance. Not exactly vanity, though she obviously knew and treasured her beauty. Then Marius mentally shrugged, dismissed the problem and Julilla; neither was ever going to be his concern.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «1. First Man in Rome»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «1. First Man in Rome» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «1. First Man in Rome» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.