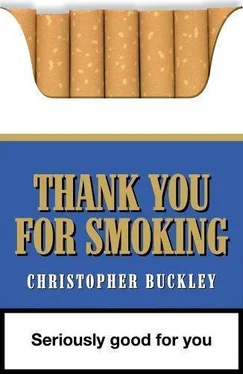

As for himself, wrote His Grace, smoking was "a custome loathsome to the eye, hatefull to the nose, harmefull to the braine, dangerous to the lungs and in the blacke stinking fume thereof, nearest resembling the horrible, Stigian smoke of the pit that is bottomlesse."

By 1612, however, James I was having second thoughts. His exchequer was bursting at the bolts with the import duties on tobacco from the Virginia colony in the James River Valley. In fact, nothing further was heard from His Majesty ever again on the loathesome custome. And thus it has remained, in a way, even to the present day, as the U.S. government goes about like Captain Renaud in Rick's Cafe shouting, "I'm shocked — shocked!" while its trade representatives squeeze foreign governments — particularly Asian ones — to relax their own warning labels and tariffs and let in U.S. weed.

"Mind if I smoke?"

The Rev looked momentarily stricken. "No. Please, yes, by all means."

Nick lit up a Camel, but refrained from blowing one of his nice tight smoke rings, despite what a nice halo it would have made around the Rev's head. "Ashtray?"

"Of course, let's see," the Rev fumbled, looking helplessly around the study. "We must have an ashtray, somewhere." But there was nothing, and with Nick's cigarette already lit, the fuse was, so to speak, burning. Nick took deep drags, hastening the process.

"Margaret," the Rev said desperately into the phone, "do we have an ashtray anywhere? Anything, yes." He sat down.

"We're finding one."

Nick took in another deep drag. The cigarette hovered over the Persian rug. The door opened, Margaret bearing a chipped tea plate embossed with the coat of arms of Saint Euthanasius. "This was all I could find," she said in a voice somewhere between embarrassment and resentment that she had been called upon to play enabler to the blacke stinking fume.

"Yes, thank you, Margaret," said the Rev, nearly grabbing the plate and handing it over to Nick mere seconds before the ash fell onto the school motto: Esto Excellens Inter Se. ("Be Excellent to Each Other.")

"Mainly," Nick said, "we sponsor sports events. But we might be able to work something out." "Wonderful," the Rev said.

"I'll have to run it by our Community Activities people. But we speak the same language."

"Marvelous," said the Rev, twisting in his Queen Anne chair. "I wonder, would it be necessary to. promulgate the. exact provenance of the underwriting?"

" 'Underwriting by the Academy of Tobacco Studies' on the programs?" Nick exhaled. "That is pretty standard."

"Yes, certainly. Yes. I was only wondering if perhaps there was some other. corporate entity that we could acknowledge. Generously, of course."

"Hm," Nick said. "Well, there is the Tobacco Research Council."

"Yes," the Rev said with disappointment, "I suppose." The TRC had been in the news recently because of the Benavides liability suit. It had come out that the TRC had been set up by the tobacco companies in the fifties as a front group, at a time when American smokers realized they were coughing more and enjoying it less, the idea being to persuade everyone that the tobacco industry, by gum, wanted to get to the bottom of these mysterious "health" issues, too. The TRC's first white paper blamed the rise of lung cancer and emphysema on a global surge in pollens. All this, apparently, the Rev knew.

"Are there by chance any other groups?"

Nick clasped his hands together and made a steeple. "We are affiliated with the Coalition for Health."

"Ah!" the Rev said, clapping his hands. "Perfect!"

The Rev walked Nick to his car. Nick asked, "By the way, how's Joey doing?"

"Joey?"

"My son. He's in your seventh grade."

"Ah! Extremely well," the Rev said. "Bright lad." "So everything's okay?"

"Spiffing. Well then," he shook Nick's hand, "thank you for coming. And I'll look forward to hearing from" — he winked, the dog-collared son of a bitch actually winked—"the Coalition for Health."

The novocaine had worn off by now, but Nick still felt pretty good and loose as he roared out of the Saint Euthanasius parking lot ahead of his bodyguards, and after the way he'd handled the Rev, entitled to his sense of triumph. The Soma had crept in on its little cat feet and was now purring in his central nervous system, hissing away all bad thoughts. He lost Mike and the boys by executing a sudden left turn at a red light off Massachusetts Avenue, narrowly avoiding an oncoming dry cleaning van and almost flattening a group of Muslims returning from prayer at the mosque; at which point it occurred to him that Dr. Wheat had told him not even to drive, much less play Parnelli Jones in city traffic.

Jeannette reached him on the car phone to say that she needed to get with him on media planning for next week's Environmental Protection Agency's report on second-hand smoke. Yet another bit of good news on the tobacco horizon. Erhardt, their scientist in residence, was cranking up the report about tobacco retarding the onset of Parkinson's disease.

"I'll be there in ten minutes," Nick said, feeling a little tired at the prospect of another meeting. His whole life was meetings. Did they have this many meetings in the Middle Ages? In Ancient Rome and Greece? No wonder their civilizations died out, they probably figured decadence and the Visigoths were preferable to more meetings.

"I'm going to swing by Cafe Ole, pick up some cappuccino," he yawned, feeling a little Somatose. "You want some?"

"God, please."

He parked in the basement garage — no sight of Mike, Jeff, and Tom, he noted with satisfaction; some bodyguards — and made his was upstairs to the Atrium. There were a dozen food places here with names like Peking Gourmet (very low mein and chicken MSG), Pasta Pasta (sold by weight), RBY (Really Bodacious Yoghurt), and So What's Not To Like Bagel. There were tables around the fountain where people could eat. It was a nice place to eat lunch, especially during the Washington summers when no one wanted to venture out onto melting sidewalks.

Nick was standing in front of the counter at Cafe Ole waiting for his two double cappuccinos when he became aware of someone staring at him. He turned but didn't see anyone, except for a bum. Having been born in 1952, he still thought of them as "bums," rather than "the homeless," though he was careful never to call them that. In fact, he had tried to set up a program whereby the cigarette companies would distribute free cigarettes to homeless shelters, but the gaspers got wind of it and got HHS to stop it, so it was no free smokes for those who needed them most.

Nick recognized most of the bums who would pandhandle in the Atrium until Security chased them away, but not this one. Quite a specimen he was, a hulking, big figure, and talk about the Grunge Look — he was wearing the remnants of about a dozen overcoats. The hair hung down in greasy clumps over his face, which looked like it had last seen soap and water during the seventies. He approached.

"Gaaaquadder?" His eyes were clearer than most of these guys', which looked like bad egg yolks.

Nick gave him a dollar and asked him if he wanted a cigarette.

"Gaaaablessyoubruhh." Nick gave him the rest of the pack.

"Gaaaamash?" Nick gave him a disposable lighter. His cappuccinos were ready. He headed off for the escalator that led up to the lobby where the office elevators were. The homeless guy followed along. Nick wasn't looking for a relationship here, but being a lapsed Catholic, he would never be entirely sure, despite his certainty that it was all a crock, that one of these wretches wasn't the mufti Christ checking to see who was being charitable toward the least of his creatures, and who wasn't and was therefore going to have such a hot time in the eternal hereafter as to make a Washington summer seem Antarctic by comparison.

Читать дальше