Author’s Note

Some real people appear here under their own names, but this is fiction.

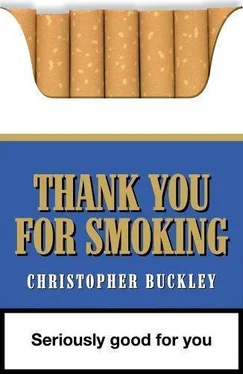

Nick Naylor had been called many things since becoming chief spokesman for the Academy of Tobacco Studies, but until now no one had actually compared him to Satan. The conference speaker, himself the recipient of munificent government grants for his unyielding holy war against the industry that supplied the coughing remnant of fifty-five million American smokers with their cherished guilty pleasure, was now pointing at the image projected onto the wall of the cavernous hotel ballroom. There were no horns or tail; he had a normal haircut, and looked like someone you might pass in the hallway, but his skin was bright red, as if he'd just gone swimming in nuclear reactor water; and the eyes — the eyes were bright, alive, vibrantly pimpy. The caption was done in the distinctive cigarette-pack typeface, "Hysterica Bold," they called it at the office. It said, warning: some people will say anything to sell cigarettes.

The audience — consisting of 2,500 "health professionals," thought Nick, who leafing through the list of participants, counted few actual M.D.s — purred at the slide. Nick knew this purr well. He caught the whiff of catnip in the air, imagined them sharpening their claws on the sides of their chairs. "I'm certain that our next. panelist," the speaker hesitated, the word just too neutral to describe a man who earned his living by killing 1,200 human beings a day. Twelve hundred people — two jumbo jet planeloads a day of men, women, and children. Yes, innocent children, denied their bright futures, those happy moments of scoring the winning touchdowns, of high school and college graduations, marriage, parenthood, professional fulfillment, breakthroughs in engineering, medicine, economics, who knows how many Nobel Prize winners? Lambs, slaughtered by Nicholas Naylor and the tobacco industry fiends he so slickly represented. More than 400,000 a year! And approaching the half-million mark. Genocide, that's what it was, enough to make you weep, if you had a heart, the thought of so many of these. victims, their lives stubbed out upon the ashtray of corporate greed by this tall, trim, nicely tailored forty-year-old yuppie executioner who, of course, "needs. no. introduction."

Not much point in trying to soften up this crowd with the usual insincere humor that in Washington passed for genuine self-deprecation. Safer to try insincere earnestness. "Believe it or not," he began, fidgeting with his silk tie now to show that he was nervous when in fact he was not, "I'm delighted to be here at the Clean Lungs 2000 symposium." With the twentieth century fast whimpering and banging its way to a conclusion, every conference in sight was calling itself Blah Blah 2000 so as to confer on itself a sense of millennial urgency that would not be lost on the relevant congressional appropriations committees, or "tits" as they were privately called by the special interest groups who made their livelihood by suckling at them. Nick wondered if this had been true of conferences back in the 1890s. Had there been a federally subsidized Buggy Whips 1900 symposium?

The audience did not respond to Nick's introductory outpouring of earnestness. But they weren't hissing at him. He glanced down at the nearest table, a roundtable of dedicated haters. The haters usually took the closest seats, scribbling furiously on their conference pads— paid for by U.S. taxpayers — which they'd found inside their pseudo-suede attaches, also paid for by amber waves of taxpayers, neatly embossed with the conference's logo, clean lungs 2000. They would take those home with them and give them to their kids, saving the price of a gift T-shirt. My folks went to Washington and all I got was this dippy attache. The haters, whipped by the previous speakers into ecstasies of Neo-Puritanical fervor, were by now in an advanced state of buttlock. They glowered up at him.

"Because," Nick continued, already exhausted by the whole dreary futility of it, "it is my closely held belief that what we need is not more confrontation, but more consultation." A direct steal from the Jesse Jackson School of Meaningless but Rhymed Oratory, but it worked. "And I'm especially grateful to the Clean Lungs 2000 leadership for. "a note of wry amusement to let them know that he knew that the Clean Lungs 2000 leadership had fought like marines on Mount Suribachi to keep him out of the conference". finally agreeing to make this a conference in the fullest sense of that word. It's always been my closely held belief that with an issue as complex as ours, what we need is not more talking about each other, but more talking to each other." He paused a beat to let their brains process his subtle substituting of "issue" for "the cigarette industry's right to slaughter half a million Americans a year."

So far so good. No one stood up and shouted, "Mass murderer!" Difficult to get back on track after being compared to Hitler, Stalin, or Pol Pot.

But then it happened, during the Q and A. Some woman about halfway back got up, said that Nick "seemed like a nice young man," prompting guffaws; said she wanted "to share a recent experience" with him. Nick braced. For him, no "shared experience" with anyone in this crowd could possibly bode well. She launched into a graphic account of a dear departed's "courageous battle" with lung cancer. Then, more in sadness than in anger, she asked Nick, "How can you sleep at night?"

No stranger to these occasions, Nick nodded sympathetically as Uncle Harry's heroic last hours were luridly recounted. "I appreciate your sharing that with us all, ma'am, and I think I speak for all of us in this room when I say that we regret your tragic loss, but I think the issue here before us today is whether we as Americans want to abide by such documents as the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights. If the answer is yes, then I think our course is clear. And I think your uncle, who was I'm sure a very fine man, were he here today, might just agree that if we go tampering with the bedrock principles that our Founding Fathers laid down, many of whom, you'll recall, were themselves tobacco farmers, just for the sake of indulging a lot of frankly unscientific speculation, then we're placing at risk not only our own freedoms, but those of our children, and our children's children." It was crucial not to pause here to let the stunning non sequitur embed itself in their neural processors. "Anti-tobacco hysteria is not exactly new. You remember, of course, Murad the Fourth, the Turkish sultan." Of course no one had the faintest notion who on earth Murad the Fourth was, but people like a little intellectual flattery. "Murad, remember, got it into his head that people shouldn't smoke, so he outlawed it, and he would go out at night dressed up like a regular Turk and wander the streets of Istanbul pretending to have a nicotine fit and begging people to sell him some tobacco. And if someone took pity on him and gave him something to smoke— whammo! — Murad would behead him on the spot. And leave the body right there in the street to rot. Warning: Selling tobacco to Murad IV can be dangerous to your health." Nick moved quickly to the kill: "Myself, I'd like to think that we as a nation have progressed beyond the days of summary executions for the crime of pursuing our own definition of happiness." Thus, having compared the modern American anti-smoking movement to the depredations of a bloodthirsty seventeenth-century Ottoman, Nick could depart, satisfied that he had temporarily beaten back the horde a few inches. Not a lot of ground, but in this war, it was practically a major victory.

There was a thick stack of while you were outs when he got back to the Academy's office in one of the more interesting buildings on K Street, hollowed out in the middle with a ten-story atrium with balconies dripping with ivy. The overall effect was that of an inside-out corporate Hanging Gardens of Babylon. A huge neo-deco-classical fountain on the ground floor provided a continuous and soothing flow of splashing white noise. The Academy of Tobacco Studies occupied the top three floors. As a senior vice president for communications at ATS, or "the Academy" as BR insisted it be called by staff, Nick was entitled to an outside comer office, but he chose an interior corner office because he liked the sound of running water. Also, he could leave his door open and the smoke would waft out into the atrium. Even smokers care about proper ventilation.

Читать дальше