Copyright © 2008 by Sofi Oksanen

Translation copyright © 2010 by Lola Rogers

Paul-Eerik Rummo’s poems are from the collection Lähettäjän osoite ja toisia runoja 1968-1972 (Sender’s Address and Other Poems, 1968-1972). Translated into English from the Finnish translations by Pirkko Huurto, Artipictura, 2005

The walls have ears, and the ears have beautiful earrings .

– Paul-Eerik Rummo

There is an answer for everything, if only one knew the question

– Paul-Eerik Rummo

Free Estonia!

I have to try to write a few words to keep some sense in my head and not let my mind break down. I’ll hide my notebook here under the floor so no one will find it, even if they do find me. This is no life for a man to live. People need people, someone to talk to. I try to do a lot of pushups, take care of my body, but I’m not a man anymore-I’m dead. A man should do the work of the household, but in my house a woman does it. It’s shameful.

Liide’s always trying to get closer to me. Why won’t she leave me alone? She smells like onions.

What’s keeping the English? And what about America? Everything’s balanced on a knife edge-nothing is certain.

Where are my girls, Linda and Ingel? The misery is more than I can bear.

Hans Pekk, son of Eerik, Estonian peasant

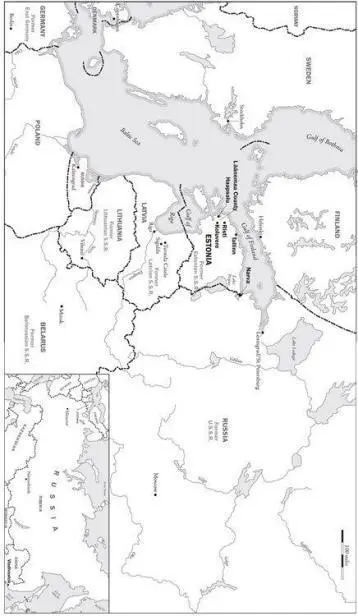

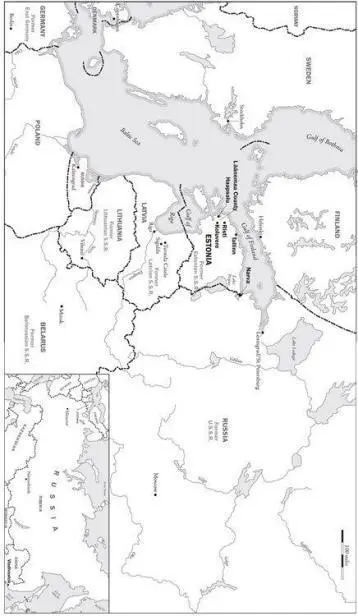

Läänemaa, Estonia

The Fly Always Wins

Aliide Truu stared at the fly, and the fly stared back. Its eyes bulged and Aliide felt sick to her stomach. A blowfly. Unusually large, loud, and eager to lay its eggs. It was lying in wait to get into the kitchen, rubbing its wings and feet against the curtain as if preparing to feast. It was after meat, nothing else but meat. The jam and all the other canned goods were safe-but that meat. The kitchen door was closed. The fly was waiting. Waiting for Aliide to tire of chasing it around the room, to give up, open the kitchen door. The flyswatter struck the curtain. The curtain fluttered, the lace flowers crumpled, and carnations flashed outside the window, but the fly got away and was strutting on the window frame, safely above Aliide’s head. Self-control! That’s what Aliide needed now, to keep her hand steady.

The fly had woken her up in the morning by walking across her forehead, as carefree as if she were a highway, contemptuously baiting her. She had pushed aside the covers and hurried to close the door to the kitchen, which the fly hadn’t yet thought to slip through. Stupid fly. Stupid and loathsome.

Aliide’s hand clenched the worn, smooth handle of the flyswatter, and she swung it again. Its cracked leather hit the glass, the glass shook, the curtain clips jangled, and the wool string that held up the curtains sagged behind the valance, but the fly escaped again, mocking her. In spite of the fact that Aliide had been trying for more than an an hour to do away with it, the fly had beaten her in every attack, and now it was flying next to the ceiling with a greasy buzz. A disgusting blowfly from the sewer drain. She’d get it yet. She would rest a bit, then do away with it and concentrate on listening to the radio and canning. The raspberries were waiting, and the tomatoes-juicy, ripe tomatoes. The harvest had been exceptionally good this year.

Aliide straightened the drapes. The rainy yard was sniveling gray; the limbs of the birch trees trembled wet, leaves flattened by the rain, blades of grass swaying, with drops of water dripping from their tips. And there was something underneath them. A mound of something. Aliide drew away, behind the shelter of the curtain. She peeked out again, pulled the lace curtain in front of her so that she couldn’t be seen from the yard, and held her breath. Her gaze bypassed the fly specks on the glass and focused on the lawn in front of the birch tree that had been split by lightning.

The mound wasn’t moving and there was nothing familiar about it except its size. Her neighbor Aino had once seen a light above the same birch tree when she was on her way to Aliide’s house, and she hadn’t dared come all the way there, instead returning home to call Aliide and ask if everything was all right, if there had been a UFO in Aliide’s yard. Aliide hadn’t noticed anything unusual, but Aino had been sure that the UFOs were in front of Aliide’s house, and at Meelis’s house, too. Meelis had talked about nothing but UFOs after that. The mound looked like it came from this world, however-it was darkened by rain, it fit into the terrain, it was the size of a person. Maybe some drunk from the village had passed out in her yard. But wouldn’t she have heard if someone were making a racket under her window? Aliide’s ears were still sharp. And she could smell old liquor fumes even through walls. A while ago a bunch of drunks from the next house over had driven out on a tractor with some stolen gasoline, and you couldn’t help but notice the noise. They had driven through her ditch several times and almost taken her fence with them. There was nothing but UFOs, old men, and dim-witted hooligans around here anymore. Her neighbor Aino had come to spend the night at her house numerous times when those boys’ goings-on got too crazy. Aino knew that Aliide wasn’t afraid of them- she’d stand up to them if she had to.

Aliide put the flyswatter that her father had made on the table and crept to the kitchen door, took hold of the latch, but then remembered the fly. It was quiet now. It was waiting for Aliide to open the kitchen door. She went back to the window. The mound was still in the yard, in the same position as before. It looked like a person-she could make out the light hair against the grass. Was it even alive? Aliide’s chest tightened; her heart started to thump in its sack. Should she go out to the yard? Or would that be stupid, rash? Was the mound a thief’s trick? No, no, it couldn’t be. She hadn’t been lured to the window, no one had knocked at the front door. If it weren’t for the fly, she wouldn’t even have noticed it before it was gone. But still. The fly was quiet. She listened. The loud hum of the refrigerator blotted out the silence of the barn that seeped through from the other side of the food pantry. She couldn’t hear the familiar buzz. Maybe the fly had stayed in the other room. Aliide lit the stove, filled the teakettle, and switched on the radio. They were talking about the presidential elections and in a moment would be the more important weather report. Aliide wanted to spend the day inside, but the mound, visible out of the corner of her eye through the kitchen window, disturbed her. It looked the same as it had from the bedroom window, just as much like a person, and it didn’t seem to be going anywhere on its own. Aliide turned off the radio and went back to the window. It was quiet, the way it’s quiet in late summer in a dying Estonian village-a neighbor’s rooster crowed, that was all. The silence had been peculiar that year-expectant, yet at the same time like the aftermath of a storm. There was something similar in the posture of Aliide’s grass, overgrown, sticking to the windowpane. It was wet and mute, placid.

Читать дальше