She had summoned Gray last night by phone while Peter contacted Marcus. The two men drove down to Kent together that morning in one of the Connaught’s black cars — wary, but incapable, in the final instance, of refusing temptation. Marcus greeted Peter as though he were a cross between Jesus Christ and a corpse He’d just revived; Jo suspected Marcus couldn’t decide whether to fire or promote him. Peter’s complete lack of interest in the outcome of the question added to his offense.

FOR AT LEAST AN HOUR AFTER FINISHING THEIR PERUSAL OF Jock’s diary the previous evening, they’d sat talking around the same table in Imogen’s office.

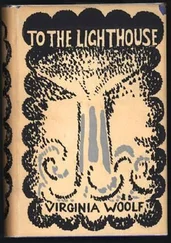

For a while, Jo simply listened to the others, her emotions brimming with the plunge into her grandfather’s past. It was painful to feel what he’d felt, to share his anxiety, to weigh the decisions he’d been forced to shoulder too soon. In the crabbed writing on the cigarette papers, Jock was a familiar stranger — not the hale old warrior she’d known, but a tentative and lonely boy, struggling to act like a man. He’d hated himself for failing the Lady that night on the London road; but how much worse must he have felt when Virginia’s body was finally pulled from the Ouse? The diary couldn’t tell Jo. But she understood that the death had scarred her grandfather beyond repair. He’d abandoned his work, his family, his life — and run away to war. Looking for a swift and violent end.

“Are you okay, Jo?” Peter asked.

She shook herself out of her reverie, smiled at him, and said, “What troubles me is that we still don’t know how Virginia died. Was she thrown, was she pushed? Or did she jump in despair?”

“She was killed in the car accident,” Peter suggested, “and her body dumped off the bridge at Southease.”

“She was brought back to Leonard,” Margaux said darkly, “who refused to waste a perfectly good death notice.”

Jo shook her head. “I think she was silenced by the men of Westminster, who drove out to find her after getting Harold’s letter. They were clever enough to take her down to Sussex, where the world already thought she’d gone into the water.”

“Harold and Vita knew otherwise,” Margaux objected.

“Harold and Vita were in the midst of a war.” Peter toyed with his mug of tea. “The Double-Cross Committee — the German agents run by M15 — were a critical reason England defeated Hitler. Harold worked for the Ministry of Information; he knew far more about intelligence work than Virginia did. He may have weighed her loss against the fate of the country — and decided not to push things.”

“That’s such a sexist statement,” Margaux said furiously. “I can’t believe you sometimes, Peter. You think it morally sound to sacrifice a genius — ”

“Harold tried his best to save her.” Peter’s voice was mild. “When he failed, he could have got himself killed, too, by protesting too much. He decided instead to go on.”

“ — Defending his Lime Walk and his English spring,” Jo murmured.

“Aren’t you glad they’re still here?” Peter shrugged. “He’d sent the truth about Blunt and Burgess to Maynard Keynes; if nobody wanted to believe it — that was hardly Harold’s problem. He wasn’t the sort to expose his fellows.”

“Lest they expose him,” Margaux shot back. “But murder?”

“We’ll never know whether it was murder,” Peter reminded her gently.

“We know,” Jo said.

BEFORE THEY LEFT SISSINGHURST THAT NIGHT, PETER placed the cigarette papers, Leonard’s letter and book, and the biscuit tin in a plastic bag. Imogen sealed it with tape and they all signed it with a black marker; then she photographed the bundle and locked it in her office safe.

“I can tell The Family I was in on the find with a straight face, now,” she said with exultant relief.

MARCUS SYMONDS-JONES WAS LOOKING AT JO THIS MORNING as though she were a particularly recalcitrant child. “I don’t think, you know, that you’re in any position to make demands. Given your extraordinary behavior in recent days. The people at this table are all that stand between you and prosecution.”

Jo smiled at him. “Did you learn that trick of intimidation from Gray? I suppose you’ll offer me a document to sign, now.”

“As a matter of fact — ” Marcus lifted a sheet of paper from the agenda before him. “I have it here. You relinquish any claim to these items in exchange for a leniency I only hope we can guarantee. I have not yet consulted the Trust or the Nicolson Family — God knows what penalties they might enforce — but we will try to do our best by you, Miss Bellamy.”

“How fortunate, then,” Peter interjected, “that we consulted The Family ourselves.”

Marcus paused. He glanced at Gray, who was studying Peter with an interested expression.

“That’s why we thought it best to meet here, in the garden, where the papers belong,” Peter added quietly. “The Family were delighted to learn from Imogen that she’d unearthed a number of treasures related to Sissinghurst and its more famous occupants; and they felt we might be interested in a final document that has come to light.” Peter paused, aware that the room had gone silent. “A poem, to be precise, written by Vita Sackville-West and found after her death.”

“Where?” Margaux demanded. “In the Tower? I swear, there’s more bloody stuff up there than anybody realizes. The Trust just sits on it.”

“The Family, not the Trust, found this particular poem — and to them, it was inexplicable. But they kept it safe.”

“Inexplicable?” Gray repeated. “In what way?”

“In the way that any piece of a puzzle is meaningless without the rest. The poem is entitled ‘In Memoriam: White Garden.’ It’s dated April 1941.”

“That’s when she published her Woolf poem,” Margaux exclaimed.

“Spot on,” Peter agreed. “Vita wrote ‘In Memoriam: Virginia Woolf’ for the London Observer that April. This poem — the one found in the Tower — would appear to be a companion to it. A more intimate lament, if you will, that she suppressed. Dr. Strand, can you recall any of the published poem?”

Margaux pursed her lips and closed her eyes, lost in thought for a few seconds. Then she intoned: “So let us say, she loved the water-meadows, / The Downs; her friends; her books; her memories; / The room which was her own. / London by twilight; shops and Mrs. Brown; / Donne’s church; the Strand; the buses, and the large / Smell of humanity that passed her by…” Margaux’s eyes drifted open. “Vita goes on to compare Virginia to a moth, fluttering against a lamp. And then she closes with:

How small, how petty seemed the little men / Measured against her scornful quality .

We feminists love to quote that bit.”

“What do you think of it? As poetry, I mean?”

“Not entirely successful.” Margaux was enjoying her moment on the stage. “Vita seemed torn between a private tribute and a public one, the need to mourn her friend and the need to ensure Virginia’s place in the English canon. That tension’s evident in the verse — ”

Marcus shifted irritably in his seat. “Yes, yes, all very delightful I’m sure — but to what does this chatter tend?”

Peter drew what appeared to be a simple sheet of writing paper from a manila envelope and placed it gently in the middle of the table.

In Memoriam: White Garden

I said she was a moth, fluttered spirit, delicate;

That bumped against the lamp of life. No mention made

Of how they tortured her, prey to nameless fears,

With such exact descriptions of the night:

Its quality, deception, unnumbered shades of grey

Читать дальше