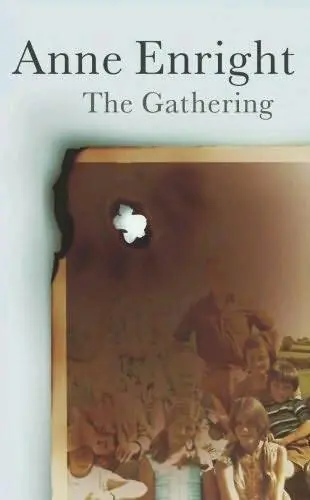

Anne Enright

The Gathering

© 2007

I WOULD LIKEto write down what happened in my grandmother’s house the summer I was eight or nine, but I am not sure if it really did happen. I need to bear witness to an uncertain event. I feel it roaring inside me-this thing that may not have taken place. I don’t even know what name to put on it. I think you might call it a crime of the flesh, but the flesh is long fallen away and I am not sure what hurt may linger in the bones.

My brother Liam loved birds and, like all boys, he loved the bones of dead animals. I have no sons myself, so when I pass any small skull or skeleton I hesitate and think of him, how he admired their intricacies. A magpie’s ancient arms coming through the mess of feathers; stubby and light and clean. That is the word we use about bones: Clean .

I tell my daughters to step back, obviously, from the mouse skull in the woodland or the dead finch that is weathering by the garden wall. I am not sure why. Though sometimes we find, on the beach, a cuttlefish bone so pure that I have to slip it in my pocket, and I comfort my hand with the secret white arc of it.

You can not libel the dead, I think, you can only console them.

So I offer Liam this picture: my two daughters running on the sandy rim of a stony beach, under a slow, turbulent sky, the shoulders of their coats shrugging behind them. Then I erase it. I close my eyes and roll with the sea’s loud static. When I open them again, it is to call the girls back to the car.

Rebecca! Emily!

It does not matter. I do not know the truth, or I do not know how to tell the truth. All I have are stories, night thoughts, the sudden convictions that uncertainty spawns. All I have are ravings, more like. She loved him! I say. She must have loved him! I wait for the kind of sense that dawn makes, when you have not slept. I stay downstairs while the family breathes above me and I write it down, I lay them out in nice sentences, all my clean, white bones.

SOME DAYS Idon’t remember my mother. I look at her photograph and she escapes me. Or I see her on a Sunday, after lunch, and we spend a pleasant afternoon, and when I leave I find she has run through me like water.

‘Goodbye,’ she says, already fading. ‘Goodbye my darling girl,’ and she reaches her soft old face up, for a kiss. It still puts me in such a rage. The way, when I turn away, she seems to disappear, and when I look, I see only the edges. I think I would pass her in the street, if she ever bought a different coat. If my mother committed a crime there would be no witnesses-she is forgetfulness itself.

‘Where’s my purse?’ she used to say when we were children-or it might be her keys, or her glasses. ‘Did anyone see my purse?’ becoming, for those few seconds, nearly there, as she went from hall, to sitting room, to kitchen and back again. Even then we did not look at her but everywhere else: she was an agitation behind us, a kind of collective guilt, as we cast about the room, knowing that our eyes would slip over the purse, which was brown and fat, even if it was quite clearly there.

Then Bea would find it. There is always one child who is able, not just to look, but also to see. The quiet one.

‘Thank you. Darling.’

To be fair, my mother is such a vague person, it is possible she can’t even see herself. It is possible that she trails her fingertip over a line of girls in an old photograph and can not tell herself apart. And, of all her children, I am the one who looks most like her own mother, my grandmother Ada. It must be confusing.

‘Oh hello,’ she said as she opened the hall door, the day I heard about Liam.

‘Hello. Darling.’ She might say the same to the cat.

‘Come in. Come in,’ as she stands in the doorway, and does not move to let me pass.

Of course she knows who I am, it is just my name that escapes her. Her eyes flick from side to side as she wipes one after another off her list.

‘Hello, Mammy,’ I say, just to give her a hint. And I make my way past her into the hall.

The house knows me. Always smaller than it should be; the walls run closer and more complicated than the ones you remember. The place is always too small.

Behind me, my mother opens the sitting room door.

‘Will you have something? A cup of tea?’

But I do not want to go into the sitting room. I am not a visitor. This is my house too. I was inside it, as it grew; as the dining room was knocked into the kitchen, as the kitchen swallowed the back garden. It is the place where my dreams still happen.

Not that I would ever live here again. The place is all extension and no house. Even the cubby-hole beside the kitchen door has another door at the back of it, so you have to battle your way through coats and hoovers to get into the downstairs loo. You could not sell the place, I sometimes think, except as a site. Level it and start again.

The kitchen still smells the same-it hits me in the base of the skull, very dim and disgusting, under the fresh, primrose yellow paint. Cupboards full of old sheets; something cooked and dusty about the lagging around the immersion heater; the chair my father used to sit in, the arms shiny and cold with the human waste of many years. It makes me gag a little, and then I can not smell it any more. It just is. It is the smell of us.

I walk to the far counter and pick up the kettle, but when I go to fill it, the cuff of my coat catches on the running tap and the sleeve fills with water. I shake out my hand, and then my arm, and when the kettle is filled and plugged in I take off my coat, pulling the wet sleeve inside out and slapping it in the air.

My mother looks at this strange scene, as if it reminds her of something. Then she starts forward to where her tablets are pooled in a saucer, on the near counter. She takes them, one after the other, with a flaccid absent-mindedness of the tongue. She lifts her chin and swallows them dry while I rub my wet arm with my hand, and then run my damp hand through my hair.

A last, green capsule enters her mouth and she goes still, working her throat. She looks out the window for a moment. Then she turns to me, remiss.

‘How are you. Darling?’

‘Veronica!’ I feel like shouting it at her. ‘You called me Veronica!’

If only she would become visible, I think. Then I could catch her and impress upon her the truth of the situation, the gravity of what she has done. But she remains hazy, unhittable, too much loved.

I have come to tell her that Liam has been found.

‘Are you all right?’

‘Oh, Mammy.’

The last time I cried in this kitchen I was seventeen years old, which is old for crying, though maybe not in our family, where everyone seemed to be every age, all at once. I sweep my wet forearm along the table of yellow pine, with its thick, plasticky sheen. I turn my face towards her and ready it to say the ritual thing (there is a kind of glee to it, too, I notice) but, ‘Veronica!’ she says, all of a sudden and she moves-almost rushes-to the kettle. She puts her hand on the bakelite handle as the bubbles thicken against the chrome, and she lifts it, still plugged in, splashing some water in to heat the pot.

He didn’t even like her.

There is a nick in the wall, over by the door, where Liam threw a knife at our mother, and everyone laughed and shouted at him. It is there among the other anonymous dents and marks. Famous. The hole Liam made, after my mother ducked, and before everyone started to roar.

Читать дальше