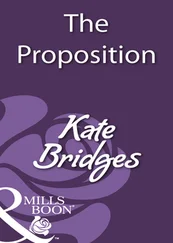

The Gathering Storm

Katerina Trilogy - 1

by

Robin Bridges

For Parham, who is grander than any duke or prince

And men loved darkness rather than light

JOHN 3:19

A NOTE ABOUT RUSSIAN NAMES AND PATRONYMICS

Russians have two official first names: a given name and a patronymic, or a name that means “the son of” or “the daughter of.” Katerina Alexandrovna, for example, is the daughter of a man named Alexander. Her brother is Pyotr Alexandrovich. A female patronymic ends in “-evna” or “-ovna,” while a male patronymic ends in “-vich.”

It was traditional for the nobility and aristocracy to name their children after Orthodox saints, thus the abundance of Alexanders and Marias and Katerinas. For this reason, nicknames, or diminutives, came in handy to tell the Marias and the Katerinas apart. Katerinas could be called Katiya, Koshka, or Katushka. An Alexander might be known as Sasha or Sandro. A Pyotr might be called Petya or Petrusha. When addressing a person by his or her nickname, one does not add the patronymic. The person would be addressed as Katerina Alexandrovna or simply Katiya.

Summer 1880, St. Petersburg, Russia

Our family tree has roots and branches reaching all across Europe, from France to Russia, from Denmark to Greece, and in several transient and minute kingdoms and principalities in between. This tree is tangled with all the rest of Europe’s royalty, and like many in that forest, my family tree is poisoned with a dark evil.

When I was seven, I sneaked into Maman’s red-and-gold parlor and watched one of her séances from behind one of the Louis XVI sofas. She and her friends were forever trying to summon relatives or famous people, as it was a fashionable pastime among the aristocracy. I do not know whose spirit they evoked, but a chill settled in the room that night as all the candles went out. My thin summer nightgown did nothing to keep me warm.

A sad lady in white appeared in the gilded Italian mirror over the fireplace. She told Maman she would never have grandchildren.

I’d never seen my mother turn so pale. Her hands trembled and the teacup she was holding began to shake. One of the other ladies—my aunt, I think—screamed and fainted.

It upset Maman so much I wanted to bring the lady in white back myself so she could tell Maman something happier. I ran out into the garden and under the lilac tree, closed my eyes, and chanted the nonsense words I’d heard Maman say. A cold, clammy feeling washed over me again, and I smelled the most horrible wet-earth smell of decay and rot. The garden began to fill with a gray, damp mist. This had been a foolish mistake.

I looked around in fear, but there were no spirits present in the garden at all. I breathed a sigh of relief and felt silly. The games Maman and her friends played were just that—games. I told myself that Maman had simply gotten carried away.

But then I spotted something on the ground under the lilac tree. I bent down to look more closely. A toad lay on his back, not breathing, his eyes a blank black stare.

I wondered what had killed him. I wished aloud that he had not died.

Still not breathing, now the toad blinked and uttered a long, mournful croak. Slowly, his pale belly began to move as he stirred to life. His stare was still blank, but the toad croaked again as he righted himself and crept closer to me.

I jumped back in terror. My throat closed up and I felt as if I couldn’t breathe. Had I brought this creature back to life, merely by wishing it? This was horribly wrong. I ran inside, ignoring the mud on my nightgown, ignoring my dirty bare feet. Too frightened to step quietly, I made a terrible racket racing up the main stairs and knocked one of Maman’s favorite cloisonné-studded icons from the wall. I did not stop to retrieve the broken frame. I just kept running.

I hurried up to the children’s floor, where I climbed into my bed and hid under the quilt. I pretended to be asleep when my nurse came upstairs to check on me.

The scent of death and decay was gone. All I could smell was the comfortable scent of my bed linens, which had been washed in rose water. The nurse left after laying her fat, cold hand against my cheek. I could smell the lemon and vodka on her fingers from her bedtime tea.

I never said a word about the toad to anyone.

Fall 1888, St. Petersburg, Russia

An afternoon spent solving quadratic equations would have been infinitely more pleasant. I smelled like a salad. Cucumber slices for soothing puffy eyes. Blackberry vinegar for brightening dull skin. Goat’s milk and honey for softening rough hands. I politely declined when my cousin offered a pinch of her goose-lard-and-pomegranate facial cream.

It was Friday afternoon and our lessons had been canceled at the Smolny Institute so everyone could prepare for the ball. Because dressing up like a doll was much more important than studying literature or learning arithmetic.

Matrimony. That was the true mission of the Smolny Institute for Young Noble Maidens. It was nothing more than a meat market for Russia’s nobility, where princes from all across Europe sent their daughters, intending them to marry well. So there I sat, Katerina Alexandra Maria von Holstein-Gottorp, Duchess of Oldenburg. Great-great-granddaughter of Empress Josephine on my mother’s side, great-great-great-granddaughter of Katerina the Great on my father’s side. Princess of the royal blood. Royal meat for sale. I would rather have been dead.

I once told Maman I wanted to attend medical school and work at one of Papa’s hospitals in St. Petersburg or Moscow. I always accompanied her to the Oldenburg Children’s Hospital when she made her charity visits at Christmas and Easter. I thought it would be wonderful to take care of sick children and discover cures for diseases. But Maman was horrified by the idea.

“What man would marry a doctor?” she asked, not bothering to wait for an answer. “What a foolish notion!”

But someone needed to find cures for such illnesses as meningitis, which had taken my younger brother before his first birthday. Why couldn’t that someone be me? I’d been only three at the time and too little to understand, but his death had devastated our family. I could remember hearing both of my parents sobbing night after night. There had been too much death in my childhood. My brother, my grandparents, my favorite aunt. I looked forward to the future, when science could perform miracles. And when we would not have to live in fear of disease.

One of our maids, Anya Stepanova, had a brother Rudolf, who attended the School of Medicine in Kiev. My father, a great believer in philanthropy, had paid Rudolf’s tuition. I begged Anya to tell me about his studies, but they did not interest her. Even she was more absorbed with the petty female plots that went on at Smolny. As she fixed my hair for the ball, she told me and my cousin Dariya Yevgenievna the latest gossip about our fellow student Princess Elena.

“She’s a witch, I tell you,” Anya whispered as she fussed with my curls. “I saw her earlier in this very room holding a moth by one of its wings over a candle and chanting. She was making some sort of charm, I’m sure of it.”

“Don’t be ridiculous,” I said, shivering all the same. I couldn’t help feeling sorry for Elena, even if she was a witch. If she couldn’t keep her powers hidden here at Smolny, what hope did I have? Raising the dead was my own secret, a talent I kept hidden, even from myself when I could.

“It’s true,” my cousin Dariya agreed. “Do you know what the cook said about Elena’s dead sister?”

Читать дальше