The widow wished above all to be practical. You don’t want to embarrass, upset, or annoy others. You don’t want to become a spectacle of pathos, pity. The widow resolved that grief itself might become practical, routine. Though at the present time her grief was slovenly and smelly as something leaking through a cracked cellar wall.

Also her grief was demented. For often in the night she heard her husband. He’d risen from their bed in the dark, he’d slipped from the room. Possibly he was using his bathroom in the hall just outside their bedroom. Every sound of that bathroom was known to her, they’d lived together in this house for so long. In her bed on her side of the bed her heart began to pound in apprehension waiting for him to return to bed with a murmured apology Hey! Sorry if I woke you.

Maybe, he’d have called her Sophie. Dear Sophie!

Maybe, he’d have brushed her cheek with his lips. His stubbled cheek against her skin. Or maybe — this was more frequent — he’d have settled back heavily into bed wordless, into his side of the bed sinking into sleep like one sinking into a pool of dark water that receives him silently and without agitation on its surface.

Often in the night she smelled him: the sweat-soaked T-shirt, shorts he’d worn on that last night.

4

Soon then Kolkentered her dreams. Like the rapid percussive dripping of thawing icicles against the roof of the house. As she was vulnerable to these nighttime sounds so she was vulnerable to Kolkby night.

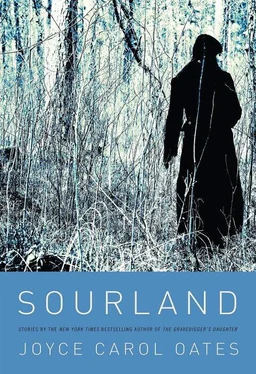

In her dreams he was a shadowy figure lacking a face. The figure in the photograph, hand uplifted.

A greeting, or a warning.

She had believed that the man was dead. The actual man, Kolk.

In their few encounters in Madison, Wisconsin, many years before they’d spoken little to each other. Kolk — was his first name Jeremiah? — had been one of Matt’s political-minded friends but not one of his closest friends and Sophie had never felt comfortable in his presence. There was something monkish and intolerant in Kolk’s manner. His soot-colored eyes behind glinting wire-rimmed glasses had seemed to crawl on her with an ascetic disdain. Who are you? Why should I care for you?

He’d never cared enough to learn her name, Sophie was sure.

It was said of Kolk that he was a farm-boy fellowship student from Wisconsin’s northern peninsula who’d enrolled in the university’s Ph.D. program to study something otherworldly and impractical like classics but had soon ceased attending classes to devote time to political matters exclusively. It was said that Kolk had an older brother who’d been a “war hero” killed in World War II. Among others in Matt’s circle who spoke readily and assertively Kolk spoke quietly and succinctly and never of himself. He had a way of blushing fiercely when he was made self-conscious or angry and often in Sophie’s memory Kolk was angry, incensed.

He’d quarreled with most of his friends. He’d insulted Matt Quinn who’d been his close friend.

He’d called Matt fink, scab. These ugly words uttered in Kolk’s raw accusing voice had been shocking to Sophie’s ears. Matt had been very angry but had said We have a difference of opinion and Kolk said sneering I think you’re a fink and you think you aren’t a fink. That’s our difference of opinion.

Sophie recalled this exchange. And Sophie recalled a single incident involving her and Kolk, long-forgotten by her as one might forget a bad dream, or a mouthful of something with a very bad taste.

Or maybe it was excitement Sophie felt. And the dread, that accompanies such excitement.

Matt hadn’t known. Sophie was reasonably sure that none of their friends had known. For Kolk wouldn’t have spoken of it.

They’d been on a stairway landing — the two of them alone together — the first time they’d been alone together for possibly Sophie had followed Kolk out onto the stairs for some reason long forgotten but recalled as urgent, crucial. And Sophie had reached out to touch Kolk’s arm — Kolk’s arm in a sleeve of his denim jacket — for Kolk was upset, to the point of tears — his face flushed and contorted in the effort not to succumb to tears — and so Sophie who wasn’t yet Matt Quinn’s young wife but the girl who lived in a graduate women’s residence but spent most of her time with Matt Quinn in his apartment on Henry Street reached out impulsively to touch Jeremiah Kolk — meaning to comfort him, that was all — and quickly Kolk pushed Sophie away, threw off her hand and turned and rapidly descended the stairs without a backward glance and that was the last time she’d seen him.

So long ago. Who would remember. No one!

Sophie had been conscious of having made a mistake, a blunder — following after Matt’s friend, who was no longer Matt’s friend. Why she’d behaved so recklessly, out of character — why she’d risked being rebuffed or insulted by Kolk — she could not have said.

Of course, it was Matthew Quinn she’d loved. It was Matt she’d always loved. For the other, she’d felt no more than a fleeting/disquieting attraction.

Not sexual. Or maybe sexual.

Who would remember…

After they were married and moved away from Madison, Wisconsin, and were living in New Haven, Connecticut, in the early 1970s — Matt was enrolled in the Yale Law School, Sophie was working on a master’s degree in art history — rumors came to them that Jeremiah Kolk had been badly injured in an accidental detonation of a “nail bomb” in a Milwaukee warehouse.

Or had Kolk been killed. He and two others had managed to escape the devastated warehouse but Kolk died of his injuries, in hiding in northern Wisconsin.

No arrests were ever made. Kolk’s name was never publicly linked to the explosion.

All that was known with certainty was that Jeremiah Kolk had never returned to study classics at the University of Wisconsin at Madison, after he’d dropped out in 1969. Long before the bombing incident he’d broken off relations with his family. He’d broken off relations with his friends in Madison. He’d disappeared.

Years later when they were living in New Jersey, one morning at breakfast Sophie saw Matt staring at a photograph in the New York Times and when Sophie came to peer at it over his shoulder saying, with a faint intake of breath, “Oh that looks like — who was it? — ‘Kolk’ — ‘Jeremiah Kolk’ — ” Matt said absently, without looking up at her, “Who?”

The photograph hadn’t been of Kolk of course but of a stranger years younger than the living Kolk would have been, in 1989.

SOPHIE —

PLEASE will you come to me Sophie this is the most alone of my life.

KOLK

P.O. Box 71

Sourland Falls

MINN

5. APRIL

Her April plans! Now the surviving spouse was sleepless for very different reasons.

Thinking It will be spring there, or almost. The worst of the ice will have thawed.

These were reasonable thoughts. There was the wish to believe that these were reasonable thoughts.

From Newark Airport she would fly to Minneapolis and from Minneapolis she would take a small commuter plane to Grand Rapids and there Kolk would meet her and drive her to his place — not home but place was the word Kolk used — in the foothills of the Sourland Mountains. By his reckoning Kolk’s place was one hundred eighty miles north and west of the small Grand Rapids airport.

By his reckoning it would take no more than three hours to drive this distance. If weather conditions were good.

Читать дальше