Sophie asked if weather conditions there were frequently not-good in that part of Minnesota.

Kolk said guardedly that there was a “range” of weather. His jeep had four-wheel drive. There wouldn’t be a problem.

Several letters had been exchanged. Sophie had covered pages in handwriting, baring her heart to Jeremiah Kolk as she’d never done to another person. For never had she written to her husband, always they’d been together. The person I am is being born only now, in these words to you, Jeremiah.

Kolk had been more circumspect. Kolk’s hand-printed letters were brief, taciturn yet not unfriendly. He wanted Sophie to know, he said, that he lived a subsistence life, in American terms. He would not present himself as anything he was not only what he’d become — A pilgrim in perpetual quest.

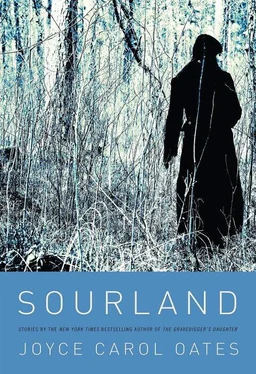

In practical terms, Kolk worked for the Sourland Mountain State Preserve. He’d lived on a nine-acre property adjacent to the Preserve for the past seven years.

Speaking with Kolk over the phone was another matter. Sophie heard herself laughing nervously. For Kolk’s voice didn’t sound at all familiar — it was raw, guttural, oddly accented as if from disuse. Yet he’d said to her — he had tried to speak enthusiastically — “Sophie? That sounds like you.”

Sophie laughed nervously.

“Well. That sounds like you. ”

After years of estrangement, when each had ceased to exist for the other, what comfort there was in the most banal speech.

They fell silent. They began to speak at the same time. Sophie shut her eyes as she’d done as a young girl jumping — not diving, she’d never had the courage to dive — from a high board, into a pool of dark-glistening lake water. Thinking If this is happening, this is what is meant to be. I will be whoever it is, to whom it happens.

Kolk had invited Sophie to visit him and to stay for a week at least and quickly Sophie said three days might be more practical. Kolk was silent for a long moment and Sophie worried that she’d offended him but then Kolk laughed as if Sophie had said something clever and riddlesome — “Three days is a start. Bring hiking clothes. If you like it here, you will want to stay longer.”

Sophie’s eyes were still shut. Sophie drew a deep breath.

“Well. Maybe.”

They would fall in love, Sophie reasoned. She would never leave Sourland.

She wanted to ask Kolk if he lived alone. (She assumed that he lived alone.) She wanted to ask if he’d been married. (She assumed that he’d never been married.) She wanted to ask how far his place was from the nearest neighbor. And what he meant by saying he was a pilgrim in perpetual quest.

Instead — boldly — impulsively as she’d reached out to touch Kolk years ago when they’d both been young — Sophie asked Kolk what she might bring him.

Quickly Kolk’s voice became wary, defensive.

“‘Bring me’ —? What do you mean?”

She’d blundered. She’d said the wrong thing. With a stab of dismay she saw Kolk — the figure that was Kolk — at the other end of the line in remote northern Minnesota — a man with a shadowy half-hidden face and soot-colored eyes behind dark glasses watching her as if she were the enemy.

“I meant — only — if you needed anything, Jeremiah. I could bring it.”

Jeremiah. Sophie had never called Kolk by this name, in Madison. The very sound — multi-syllabic, Biblical and archaic — was clumsy in her mouth like a pebble on the tongue. But Kolk laughed again — after a moment — as if Sophie had said something witty.

“Bring yourself, Sophie. That’s all I want.”

Sophie’s eyes flooded with tears. To this remark she could think of no adequate reply.

Of course she would tell no one — not her closest friends, nor those relatives who called her frequently because they were worried about her — of her plans to fly a thousand miles to visit a man she had not seen in a quarter-century. A man whom she’d never known. A political-radical outlaw believed to be dead, who had died twenty years before in the clandestine preparation of a bomb intended to kill innocent people.

In the cemetery amid the damp grasses she stood before the small rectangular grave marker, she had not visited in months.

MATTHEW GIDEON QUINN

On this misty-cool and sunless April morning she was the only visitor in the cemetery.

The air was so stark! So sharp! Her eyes stung with tears like tiny icicles. She felt a flutter of panic, at all that she’d lost that was reduced to ashes, buried in the frozen ground at her feet.

Waiting for a revelation. Waiting for a voice. Of release, or condemnation.

I will protect you forever dear Sophie!

Was this Matt’s voice? Had she heard correctly? Had he ever made such an extravagant promise to her, he could never have kept?

Sophie was feeling light-headed, feverish. She hadn’t slept well the previous night. Her brain was livid with plans, what she would pack to take with her, what she would say to Jeremiah Kolk when they were alone together. Early the next morning she was flying out from Newark, west to Sourland, Minnesota.

“Matt? I will be back, I promise. I won’t be gone long.”

Plaintively adding, “I need to do this. Kolk needs me.”

How silent the cemetery was! Sophie felt the rebuke of the dead, their resentment of the living.

Sophie are you so desperate? Maybe you should kill yourself, instead.

6

And then, in the small grim airport at Grand Rapids, she didn’t see Kolk.

In a shifting crowd of people, most of them men, not one seemed to bear much resemblance to Jeremiah Kolk.

The flight from Minneapolis to Grand Rapids had been turbulent and noisy. For the past forty minutes which were the most protracted forty minutes of Sophie’s life the small commuter plane had shuddered and lurched as if propelled through churning water and as the plane descended at last to land Sophie felt her heart beating hard, in primitive terror. Of course, this was a mistake. Anyone could have told her, this was a mistake. Grief had made her a desperate woman.

Yet chiding herself with a sort of dazed elation No turning back! You have brought yourself to this place, where a man wants you.

The commuter plane disembarked not at a gate but on the tarmac in a lightly falling snow. One by one passengers made their perilous way down steep metal steps, that had been wheeled to the plane. There was an elderly woman with a cane, who had to be assisted. There was a heavyset Indian-looking man with a splotched face, whose wheezing breath was frightening to Sophie, who had to be assisted. Sophie had the idea — it was a comforting idea — or should have been a comforting idea — that her friend must be just inside the terminal watching — watching for her — and so she made her way down the metal steps calmly if in a haze of anticipation, a small mysterious smile on her lips.

No turning back!

And then inside the terminal — her deranged girl’s heart was beating very hard now — she didn’t see him. At the lone baggage carousel she didn’t see him. No one? No Kolk? After their letter-exchanges, their telephone conversations? Sophie stared, at a loss. Several men who might have been Kolk — of Kolk’s age, or approximately — passed her by without a glance. A rat-faced youngish man with ragged whiskers and hair tied back in a ponytail passed so closely by Sophie that she could smell his body, without glancing at her.

Sophie thought My punishment has begun. This, I have brought on myself.

Kolk had provided her with a single telephone number, in case of emergency — not his home or cell phone number but that of the auto repair in Sourland Junction. Useless to her, now!

Читать дальше