Sophie laid the photographs on the dining room table. Like dealing out cards this was, in a kind of riddle. It seemed to her — unless her heightened nerves were causing her to imagine this — that some of the wilderness scenes overlapped.

A steep rock-strewn mountainside, a basin-like terrain covered in immense boulders of the shape and hue of eggs, harsh bright autumn sunlight so dazzling that the colors it touched were bleached out…Most beautiful was a narrow mountain stream falling almost vertically, amid sharp-looking rocks like teeth.

A strange dreaminess overcame her, like a sedative. She was seeing these stark beautiful scenes through the photographer’s eyes — it had to be K.who held the camera — it was K.who’d sent her the photographs.

Is this where I will be taken? Why?

She realized — her forefinger was stinging. A tiny paper cut near her cuticle leaked blood.

She saw — her fingers were covered in such tiny cuts. The furnace-heated air in the house was so dry, her skin had become sensitive and susceptible to cuts. Opening mail, unwanted packages, “gift” boxes from the well-intentioned who imagined that a widow craves useless items as compensation perhaps for having lost her husband…

In the following days as she passed through the dining room she paused to examine the photographs. Very like a visual riddle they were — pieces of a jigsaw puzzle like the puzzles she’d patiently pieced together as a child — of wilderness scenes, or landscape paintings. Shaking herself awake then as out of a narcotic stupor.

Those days! Grief, very like dirty water splashed into her mouth. Yet she had no choice, she must swallow.

Not wanting to accuse the husband Why did you abandon me! I’d trusted you with my life.

It was a posthumous life, you would have to concede. Though no one wishes to acknowledge the fact. Though there is every reason to wish not to acknowledge the fact. Long stretches of time — vast as the Sahara — she was the surviving spouse and thus never fully awake — and yet she was never fully asleep. Never was she deeply, refreshingly asleep. When it became “day” — after the winter solstice, at ever-earlier hours — she could not bear to remain in bed. And once up, she had to keep in motion. She could walk, walk, walk for as many as forty, fifty — sixty — minutes at a time, in a kind of spell of self-laceration. Fierce with energy she cleaned out closets, cleaned the basement, on her hands and knees cleaned the hardwood floors with paper towels and polish. Never did she find herself in the right room — invariably she’d forgotten something, that was in another room. It was becoming impossible — physically impossible — for her to remain in one place for more than a few seconds. Such rooms she’d shared with her husband in their daily lives — dining room, living room, a glassed-in porch at the rear of the house — she could not now occupy for long.

Ghost-rooms, these were. Except for the bedroom and the kitchen — rooms she couldn’t reasonably avoid — and the room she considered her study, that the husband had not often entered — the rooms of the house were becoming uninhabitable.

The surviving spouse inhabits a space not much larger than a grave.

Hard not to think, the husband had abandoned her to this space. Hadn’t he promised when they’d first fallen in love I will protect you forever dear Sophie! — in an extravagance of speech meant to be playful and amusing and yet at the same time serious, sincere. And so — he’d abandoned her.

This season of grief, when her mind wasn’t right.

At about the time when she’d become accustomed to — inured to — the photographs on the dining room table — it might have been several weeks, or months — the second envelope from K.arrived.

How curious the envelope! The paper was thick and grainy, oatmeal-colored, as you’d imagine papyrus. The hand-printed letters in black felt-tip pen were stark and impersonal as before.

Sophie’s heart leapt. At once she snatched the envelope out of the jammed mailbox.

No danger of spiders in the mailbox now — she’d destroyed the feathery nest and all its inhabitants. In any case it was winter, and too cold for spiders to survive outdoors.

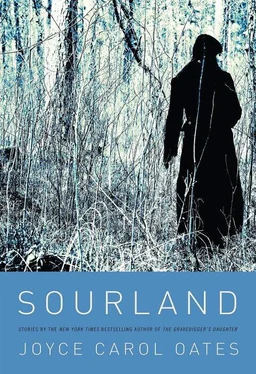

In the interval Sophie had looked up Sourland, Minnesota, in a book of maps: it was a small town, probably no more than a village, about one hundred miles north and west of Grand Rapids in what appeared to be a wilderness area of lakes, rivers, and dense forests. In addition to Sourland there was Sourland Falls, and there was Sourland Junction, and there was the vast Sourland Mountain State Preserve which consisted of more than four million acres. All these places were in Sourland County east of romantically named Lake of the Woods County and west of the Red Lake Indian Reservation in Koochiching County.

And this time too the manila envelope contained no letter, just photographs — a sparsely wooded mountainside, the interior of a pine forest permeated by shafts of sunshine, a lake of dark-glistening water surrounded by trees as the water of a deep well is surrounded by rock. In the background of another photo you could just make out a structure of some kind — a small house, or a cabin. Sophie thought Is this where he lives?

She knew, this had to be. K.was teasing her, like one dealing out cards in a specific order, to tell the story he wants told.

In the final photo, you could see that this structure was a cabin, of coarse-hewn logs. The roof was steep, covered in weathered tar paper; there was a stovepipe chimney; there were strips of unsightly plastic, to keep out the cold. In this photo there was snow on the ground, snow crusted against the cabin as if it had been blown there with tremendous force. Close by the cabin was a small clearing, stacks of firewood, an ax embedded in a tree stump.

In a rutted and mud-puddled driveway was a steel-colored vehicle with monster-tires, for the most rugged terrain. And beside this vehicle stood a bewhiskered man in a parka and khaki shorts, the hood of the parka drawn over his head; his legs were dark-tanned, ropey with muscle. Though his face was partly obscured by dark-tinted glasses, the parka hood and the bristling beard, you could see that the man’s features were severe, unsmiling though he had lifted his right hand as if in greeting.

Sophie took the photo to a window, to examine. She couldn’t make out the man’s face, that seemed to melt away in a patch of shadow.

Nor could she determine if the man was lifting his hand in a gesture of welcome, or of warning.

Hello. Go away. Come closer. Did I invite you?

So this was K.Sophie was certain she’d never seen him before.

Yet he’d addressed the envelope boldly to Sophie Quinn. If he’d known her husband, and through her husband had known of her, it was strange that he didn’t include a letter or a note in reference to Matt. For he must have known that Matt had died.

Your loss. Sorry for your loss. My condolences Sophie!

There was little that anyone could say, to assuage the fact of death. Sophie understood that people must speak to her, address her, in the rawness of her grief, who could not quite grasp what she was feeling. For she, too, had many times spoken to others distraught by grief — not able to know what it was they felt. Now, she knew. At any rate, she knew better than she’d known.

But K.wasn’t offering condolences, or solace. Sophie didn’t think so.

She remembered how, when she’d first met him, Matthew Quinn had been something of an outdoorsman. Not a hunter — no one in Matt’s family had ever hunted — but a serious hiker and camper, as a graduate student at the University of Wisconsin, at Madison. He’d never taken Sophie with him — by the time they met Matt was nearly thirty and impatient to finish his Ph.D. in American constitutional law, and leave school. He’d been impatient to begin what he called adult life.

Читать дальше