Interior realities are masterfully evinced here, too. Vanderhaeghe shines a white light into the souls of his characters, making them reveal their luminous selves when presented on the page. “Dieter lay on the chesterfield trying to stifle his tears. It was not an easy job because even the sound of Mrs. Hax unconcernedly clacking the breakfast dishes reminded him of her monstrous carelessness with everything. His plates, his feelings” (“Dancing Bear”). I challenge anyone to find a briefer, more elegant, more revealing description of any character in any book by any writer. There is writing as good as this, but none better.

Moments of great emotional and physical intensity are realized in Man Descending with a truth that rarely transfers so clearly and powerfully onto the printed page. Again and again and again in these stories, characters’ heads swim with realization or fear or disgust. People turn infirm or ill. Someone scrapes a knuckle, goes bodily numb, peels off and examines a piece of his or her own skin. And in these places, where lesser writers seldom bother to prod or when they do either blur the moment with inexact language or use it merely as a pivot point for plot, the visceral poetry of Vanderhaeghe’s prose transforms the banal into the sublime.

Ogle, in “A Taste for Perfection,” is slowly losing sensation in his extremities. In an attempt to revivify himself, he makes his way to the hospital’s physical therapy room, where he finds a basketball. As Ogle holds the ball, Vanderhaeghe tells us that “he relished the pebbly grain with his fingertips.” A brief moment of somatic contact described so aptly that in a single sentence we can feel that ball in our own hands, and in doing so enter into Ogle’s experience just long enough to understand the fullness of his desperation.

At the end of “Dancing Bear,” as Dieter is making his last grab at a measure of autonomy, Vanderhaeghe’s description is so perfect and complete that I always find myself struggling for air as I read the following passage, as though Dieter’s consciousness were closing in around me.

He tried to get up. He rose, trembling, swayed, felt the floor shift, and fell, striking his head on a chest of drawers. His mouth filled with something warm and salty. He could hear something moving in the house, and then the sound was lost in the tumult of the blood singing in his veins. His pulse beat dimly in his eyelids, his ears, his neck and fingertips.

He managed to struggle to his feet and beat his way into the roar of the shadows which slipped by like surf, and out into the hallway.

And then he saw a form in the muted light, patiently waiting. It was the bear.

“Bear?” he asked, shuffling forward, trailing his leg.

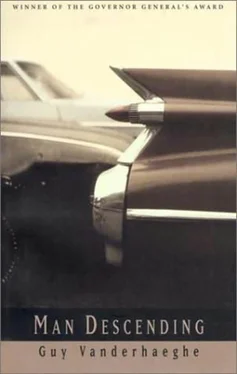

Vanderhaeghe’s vision in Man Descending is rich and encompassing. He shows us relationships between men and women, men and men, parents and children. He takes us where power meets vulnerability, where violence meets despair. All the gravity of the book is cheered by the half-light of humour. All the humour is tinged with sorrow. Man Descending gives us a lush, generous, fecund view of a complex, difficult, knuckle-barking, beautiful universe.

I began by saying that a very good book was a mystery. I’ll conclude by saying that great books, aside from being mysteries, reveal a mystery to us. A great book can transform the reader, transform the reader’s perception, transform the world. This is what reading Man Descending does for us. While our eyes are on the pages, we admire the book itself, its breadth, its insight, the mastery of its art. When we lift our eyes from the page, we see the planet as though for the first time. The sparkling particulars of creation are brought into shaper focus. We are given to wonder at the private cosmos of each person we see. We realize anew the endless possibilities of the world.

GUY VANDERHAEGHE was born in Esterhazy, Saskatchewan, in 1951. He received his B.A. (1971) and his M.A. (1975) from the University of Saskatchewan and his B.Ed. (1978) from the University of Regina.

In his first volume of fiction, twelve stories gathered together under the title Man Descending (1982), Vanderhaeghe recounts the dilemmas and the humiliations of a variety of male characters, ranging in age from childhood to old age. The collection won the Governor General’s Award for Fiction and went on to receive the Faber Prize in Great Britain. In his subsequent fiction, which includes two more collections of short stories and four novels, he has won further awards and acclaim, his recent novels being historical fiction of the west.

In addition to his fiction, Vanderhaeghe has also written two plays: I Had a Job I Liked . Once., which premiered in 1991, and Dancock’s Dance, which premiered in 1995.

Guy Vanderhaeghe lives in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan.

***