I reached over and took his hand, to protect both of us. In doing so, I caught up with my own gesture. I felt for him, a frightened soul no better prepared to face his mortality than I would be if the disease started working on me now, this moment. My face burned.

“Ready?” I said.

“Ready.”

We stepped into the water together while Bobby was getting out of his jeans. The first impression was of warmth—an inch of temperate water floated on the surface. But when we penetrated that, the water beneath was numbingly cold.

“Oh,” Erich exclaimed as it lapped his ankles.

“Maybe this isn’t a very good idea after all,” I said. “I mean, it can’t be good for you.”

“No,” he said. “Let’s just go a little ways in. I want to—well, I just want to.

“All right,” I said. I was still holding his hand. For the first time I felt intimate with him, though we had known one another for years and had made love hundreds of times. We shuffled ahead, taking tiny steps on the sandy bottom. Each new quarter-inch of flesh exposed to water was agony. The sand itself felt like granular ice under our feet.

Bobby splashed out to us. “Crazy,” he said. “Goddamn crazy. Erich, you got two minutes in here, and then I’m taking you out.”

He meant it. He would lift Erich bodily and carry him to shore if necessary. Since he and I were boys together, he had made it his business to rescue fools from icy water.

Still, we had two minutes, and we advanced. The water was clear—nets of light fluttered across our bare feet, and minnows darted away from us, visible only by their shadows skimming along the bottom. I glanced at Bobby, who was grave and steady as a steamship. He was a reverse image of Erich; time had thickened him. His belly was broad and protuberant now, and his little copper-colored medallion of pectoral hair had darkened and spread, sending tendrils up onto his shoulders and down along his back. I myself was losing hair—my hairline was at least two inches higher than it had been ten years ago. I could feel with my fingertips a rough circle at the back of my head where the growth was thinner.

“This is good,” Erich said. “I mean, well, it feels very good.”

It didn’t feel good. It was torture. But I thought I understood—it was a strong sensation, one that came from the outer world rather than the inner. He was saying goodbye to a certain kind of pain.

“You’re shivering,” Bobby said.

“One more minute. Then we’ll go in.”

“Right. One more minute, exactly.”

We stood in the water together, watching the unbroken line of trees on the opposite bank. That was all that happened. Bobby and I took Erich for what would in fact turn out to be his last swim, and waded in only to our knees. But as I stood in the water, something happened to me. I don’t know if I can explain this. Something cracked. I had lived until then for the future, in a state of continuing expectation, and the process came suddenly to a stop while I stood nude with Bobby and Erich in a shallow platter of freezing water. My father was dead and I myself might very well be dying. My mother had a new haircut, a business and a young lover; a new life that suited her better than her old one had. I had not fathered a child but I loved one as if I was her father—I knew what that was like. I wouldn’t say I was happy. I was nothing so simple as happy. I was merely present, perhaps for the first time in my adult life. The moment was unextraordinary. But I had the moment, I had it completely. It inhabited me. I realized that if I died soon I would have known this, a connection with my life, its errors and cockeyed successes. The chance to be one of three naked men standing in a small body of clear water. I would not die unfulfilled because I’d been here, right here and nowhere else. I didn’t speak. Bobby announced that the minute was up, and we took Erich back to shore.

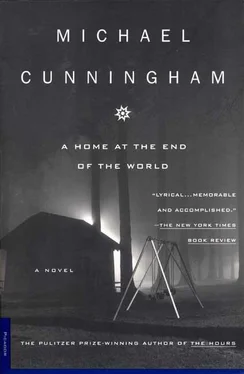

Praise for A Home at the End of the World

“Once in a great while, there appears a novel so spellbinding in its beauty and sensitivity that the reader devours it nearly whole, in great greedy gulps, and feels stretched sore afterwards, having been expanded and filled. Such a book is Michael Cunningham’s A Home at the End of the World. ”

—Sherry Rosenthal,

The San Diego Tribune

“Michael Cunningham has written a novel that all but reads itself.”

—Patrick Gale,

The Washington Post Book World

“A touching contemporary story… This novel is full of precise treasures…. A Home at the End of the World is the issue of an original talent.”

—Herbert Gold,

The Cleveland Plain Dealer

“Beautiful…This is a fine work, one of grace and great sympathy.”

—Linnea Lannon,

Detroit Free Press

“Luminous with the wonders and anxieties that make childhood mysterious… A Home at the End of the World is a remarkable accomplishment.”

—Laura Frost,

San Francisco Review

“Fragile and elegant… Cunningham employs all his talents, and they are considerable, to try to map out our contemporary emotional terrain.”

—Vince Passaro,

Newsday

“Brilliant and satisfying… as good as anything I’ve read in years… Hope in the midst of tragedy is a fragile thing, and Cunningham carries it with masterful care.”

—Gayle Kidder,

The San Diego Union

“Exquisitely written… lyrical… An important book.”

—

The Charleston Sunday News and Courier

Also by Michael Cunningham

Flesh and Blood

The Hours

Land’s End: A Walk in Provincetown

A Home at the End of the World was started during hard times. By the date of its completion—nearly six years later—things had eased somewhat. For those more comfortable circumstances I thank the National Endowment for the Art and The New Yorker .

I must reserve the bulk of my gratitude, though, for several friends whose generosity literally rescued this book during its early phases, when encouragement, shelter, and even a working typewriter were sometimes hard to find. Thanks, with love, to Judith E. Turt, Donna Lee, Cristina Thorson, and Rob and Dale Cole.

Also of immeasurable help were Jonathan Galassi, Gail Hochman, Sarah Metcalf, Anne Rumesy, Avery Russell, Lore Segal, Roger Straus, the Yaddo Corporation, and, as always, my family.

A HOME AT THE END OF THE WORLD. Copyright @ 1990 by Michael Cunningham. All rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of America.

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information, address Picador, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010.

www.picadorusa.com

Picador® is a U.S. registered trademark and is used by Farrar, Straus and Giroux under license from Pan Books Limited.

For information on Picador Reading Group Guides, as well as ordering, please contact the Trade Marketing department at St. Martin's Press.

Phone: 1-800-221-7945 extension 763

Fax: 212-677-7456

E-mail: trademarketing@stmartins.com

Two chapters of this book appeared in earlier form in The New Yorker .

Acknowledgments for permission to reprint previously published material appear on page 344

Читать дальше