“It feels right,” I said. “Don’t you get a feeling from this place?”

“Mm-hm,” Clare said. “Nausea. Vertigo. Panic.” She kept looking at her thumb.

We argued for a week, and bought the house. We bought the well and the afternoon light. We bought fifteen oaks, eight pines, a blackberry thicket, and a pair of graves so old the markers had been worn smooth as chalk. As Clare sat pregnant on a green vinyl chair signing the papers she said, “So long, Paris and Istanbul.”

Jonathan added, “So long, Armani. So long, crocodile shoes.” The two of them shared a sour little laugh. And then the deal was made. Clare had bought us all a fresh start with her dead grandfather’s rhinestone fortune. By way of celebration, the real estate agent gave us complimentary white wine in white Styrofoam cups.

When we left our New York apartment we got rid of everything worn out or broken—nearly half our possessions. We put them out on the street as offerings for the people who were just arriving, full of hope, at the place we were about to leave. We watched from the window as passers-by carried things away. A woman took the lava lamp. Two skinheads and a fat tattooed girl took the swaybacked sofa covered in leopard-skin polyester.

“So long, treasures,” Clare said. Her breath made a spool-shaped flicker of steam on the glass.

“So long, old garbage from thrift-store bins,” Jonathan said. “Honey, there are times when nostalgia is simply not called for.”

“I dragged that sofa down here from Sixty-seventh Street,” she said. “Years ago, with Stephen Cooper and Little Bill. We’d carry the damn thing a few blocks, stop and sit on it, then walk another few blocks. It took us all night. Sometimes bag people would sit on it with us, and we’d all have a beer. We made a lot of friends that night.”

“And now you’re a homeowner and a mother-to-be,” Jonathan said. “Did you really expect to scavenge around the streets of New York for the rest of your life?”

“Little Bill died,” she said. “Did I tell you?”

“No.”

“Corinne told me. He died in South Carolina, oh, at least a year ago. We’d all lost track of him.”

“I’m sorry. Is Stephen all right?”

“Oh, Stephen’s fine. He really did open a jewelry store up on Cape Cod. I suppose he’s making a mint selling little gold whales and sea gulls to tourists.”

“Well,” Jonathan said. “That’s good. I mean, at least he’s alive.”

“Mm-hm.”

We watched the sofa travel down East Fourth Street. On the sidewalk below our window, a man and a woman in leather jackets whooped over Clare’s old kitchen clock—a yellow plastic boomerang shape covered with pink-and-red electrons.

“I can’t believe I let you talk me into throwing out the clock,” she said. “I’m going to go down there and tell those people it was a mistake.”

“Forget it,” Jonathan said. “They’d kill you.”

“Jonathan, that clock is a collector’s item. It’s worth money.”

“Sweetie, it doesn’t run,” he said. “It doesn’t tell time anymore. Let them have it.”

She nodded, and watched numbly as the couple jogged away toward First Avenue, passing the clock back and forth like a football. She stroked her pregnant belly. She breathed steam onto the glass.

That was over ten months ago. Now we live in a field facing the mountains. Spiky blue flowers climb through the slats of our fence. Bees drone in their ecstasy of daily work, and a milk-blue sky hangs raggedly behind the trees. These are old mountains. They’ve been worn down by wind and rain. They are not about anarchy or grandeur, like the more photogenic ranges. These mountains throw a smooth shadow—their crags don’t imply the gnash of continental plates. They are evenly bearded with pine trees. They cut modest half-moons out of the sky.

“I hate scenery,” Clare says. “It’s so obvious.” She is standing beside me in the unmowed grass. It’s the first April of the new decade and she’s a new Clare. She’s sharper now, with more true bite under her jokes. You’d expect motherhood to have had a softening effect.

“Aw, come on,” I tell her. “Get over it, huh?”

A pair of crows glide over the house. One lets out a raucous cry, like metal twisting on metal.

“Buzzards,” Clare says. “Carrion-eaters. Waiting for the first of us to die of boredom.”

I sing softly into her ear. I sing, “By the time we got to Woodstock, we were half a million strong, and everywhere there was song and celebration.”

“Stop that,” she says, batting the song away as if it was a taunting crow. Her silver bracelets click. “If there’s one thing I never expected to end up as,” she says, “it’s an old hippie.”

“There are, you know, worse things to end up as,” I say.

“It’s too late,” she says. “The butterflies are turning back into bombers. Haven’t you noticed? They’re going to build condos on that mountain, take my word for it.”

“I don’t think they will. I don’t think there’d be enough customers.”

She looks at the mountains as if the future was written there in small, bright letters. She squints. For a moment she could be a country woman, all sinew and suspicion, and never mind about her lipstick or her chartreuse shirt. She could be my mother’s mother, standing on the edge of her Wisconsin holdings and looking out disapprovingly at the vastness of what she doesn’t own.

“As long as there are enough customers for the Home Café. Christ, I still can’t believe we decided to call it that.”

“People’ll love it,” I say.

“Oh, this is all just so weird. It’s so outdated and—weird.”

“Well, it sort of is,” I say.

“No ‘sort of’ about it.”

She is so bitter and hard, so much like her revised self, that a rogue spasm of happiness rises up in me. She’s so real; so Clare. I do a quick, spastic dance. It has nothing to do with grace or the tight invisible laws of rhythm—I could be a small wooden man on a string. Clare rolls her eyes in a wifely way. There is room here for the daily peculiarities.

She says, “I’m glad one of us feels good about all this.”

“Aw, darling, what’s not to feel good about?” I say. “We’re some thing now, I mean we won’t just blow away if one of us takes a notion.”

“It would be nice if that were true,” she says.

“You know what I’d like to do someday? I’d like to fix up the shed as a separate little house, so Alice could move up here when she gets tired of the catering business.”

“Oh, sure. Let’s build a cottage for my old fourth-grade teacher, too.”

“Clare?” I say.

“Mm-hm?”

“You really are happy here, aren’t you? I mean, this is our life. Right?”

“Oh, sure it is. It’s our life. You know me, I think in terms of complaint. It’s how my mind works.”

“Right,” I say.

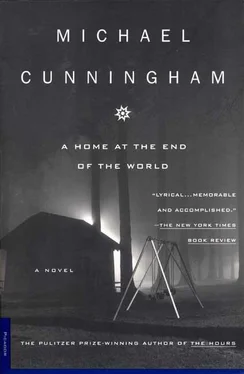

We stand watching the mountains, then turn to watch the house. This house is so old the spirits themselves have melted into the walls. It feels inhabited not by anyone’s private unhappiness but by the collected days of ten generations, their meals and fights, their births and last gasps. Now, right now, it’s a disreputable marriage of old and new disappointments. The floorboards are crumbling, and the remodeled kitchen seethes with orange linoleum and Spanish-style wood-like cabinets. We’re going to fix it up, slowly, with the money we make from our restaurant. We are forces of order, come from the city with talents and tools and our belief in a generous future. Jonathan and Clare look at the house and see what it can become. They talk antique fixtures, eight-over-eights, a limestone mantel rescued from a house in Hudson and trucked up here. Although I wouldn’t fight progress I like the house as it is, with bug-riddled floors and wood-grain chemical paneling that looks like sorrow and laziness made into a domestic fixture. Sitting on its four overgrown acres, the house answers the elderly mountains. It, too, is docile and worn smooth. It has been humbled by time.

Читать дальше