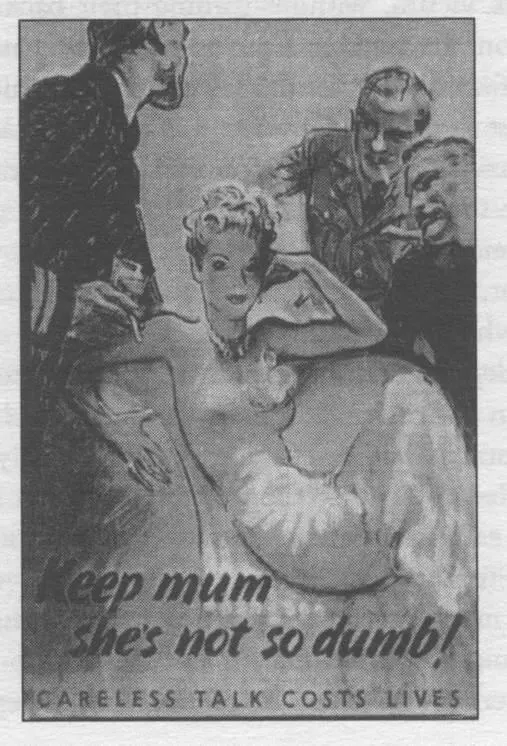

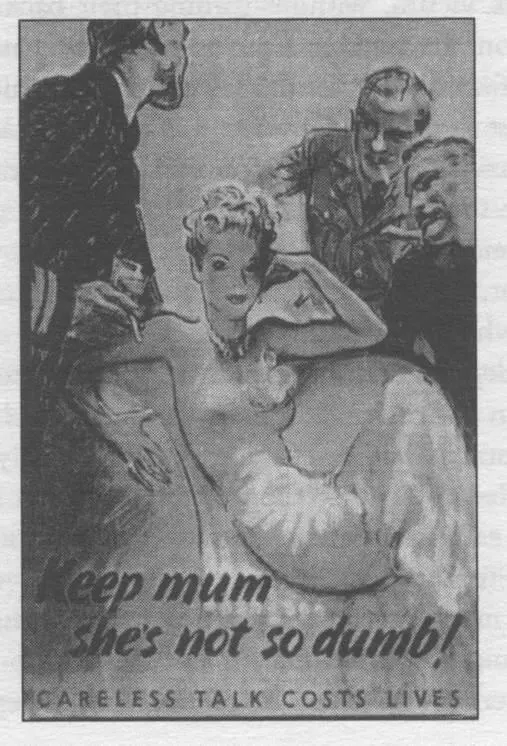

Another depicted a more worldly scene: an attractive woman lounges in an armchair (necklace, evening dress, corsage, long, painted fingernails) and stares coolly and mockingly ahead while she is encircled and courted and fawned upon by three officers at a party, each holding a cigarette and a drink, they are presumably regaling her with tales of recent escapades or announcing imminent exploits in order to impress her, or else talking amongst themselves, unconcerned that the woman might be listening to them. The caption says: 'Keep mum, she's

not so dumb!' (in Spanish: 'Chiton, ella no es tan tonta!', although in English there is a play on the word 'dumb' which means both 'silent' and 'stupid', and which also rhymes with 'mum'). In red letters underneath is the main campaign slogan: 'Careless talk costs lives.'

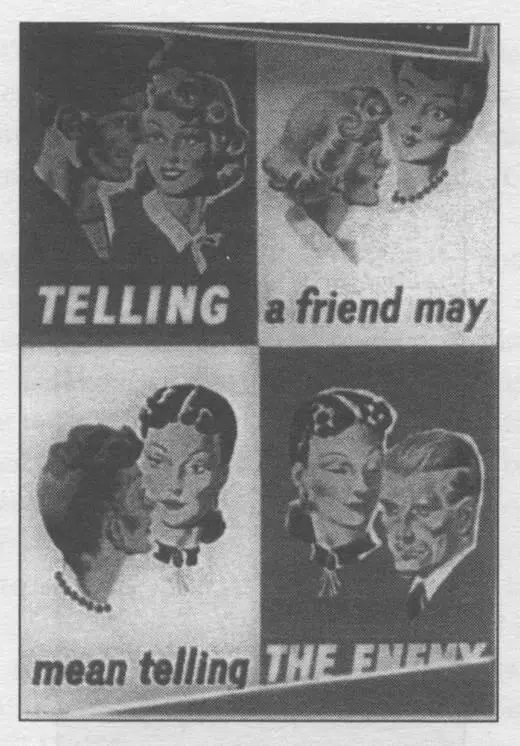

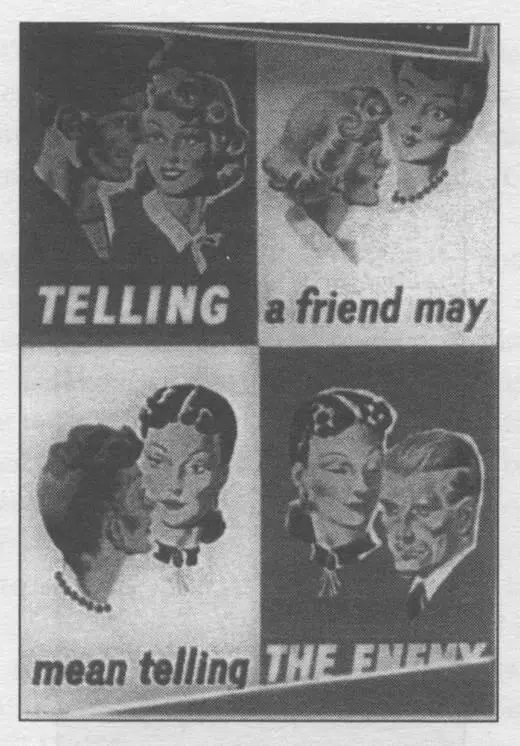

Another was even more explicit and didactic, and warned of the possible chain of communication, unwitting and uncontrollable, to which the spoken word is always vulnerable, and here the spy – male or female – is not there at the start, listening, but waiting at the end. The drawing was divided into four parts, two with a red background and two with a white background. The picture at top left showed a sailor talking to a young blonde woman (his girlfriend, his sister, perhaps a friend) whom he has no reason to distrust, on the contrary, she listens with disinterested interest (that is, she is more interested in him than in what he reveals to her or tells her), and gazes at him admiringly, almost spellbound. Underneath, in capital letters, is the word 'TELLING'. The next picture, top right, shows the same young blonde woman chatting to a female friend with brown hair drawn up on top of her head and who is listening with a look of amazement on her face, but her interest seems less disinterested: she is, at the very least, savouring in advance the prospect of passing on this titbit of news; she may not be ill-intentioned, but simply gossipy, one of those people who enjoy retailing and acquiring any hot news to show how well-informed they are and thus surprising others with how much they know about everything. Underneath, in lower-case letters, is printed: 'a friend may'. The picture at bottom left shows the woman with the brown hair telling what she has heard to another female friend, this woman has black hair parted in the middle and arranged in a kind of low bun, she has cold, almond-shaped eyes and an interested expression on her face, an expression which, this time, is entirely self-interested, for as she is listening, she is thinking of the next person she will speak to, and to whom she will give not just a snippet of news, but some very valuable information. Underneath, again in lower case, is printed: 'mean telling'. Lastly, the picture bottom right showed the third woman, the one with the black hair – her eyes malevolently closed – almost whispering into the ear of a fair-haired man with shifty eyes and very hard features, doubtless a ruthless Nazi whose next step will not be to tell someone else, but to act, to take measures that will probably result in the deaths of many men, including that of the guilty and innocent sailor. Underneath, the letters were once more printed in upper case, 'THE ENEMY', and so the whole message was 'TELLING a friend may mean telling THE ENEMY', the principal message being the one conveyed by those capital letters set against the red background. I couldn't help smiling to myself and noticing the careful gradation of the three women: the 'good' one was blonde with shortish hair and wore a simple, modest white bow around her neck; the 'frivolous' or 'silly' one wore her brown hair swept up and had a necklace on (she was more of a coquette); the 'bad' one, the spy, had black hair arranged rather more elaborately, and around her neck she was wearing a kind of black choker with a lustrous, greenish-coloured brooch in the middle, and she was also the only one to wear earrings (she was doubtless a proper femme fatale). Many of my female compatriots, amongst them my mother, would, I thought, have received a very bad press in England at that time.

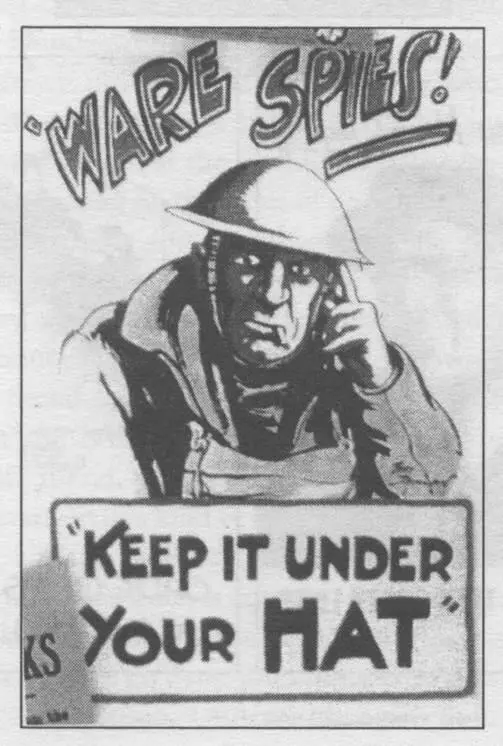

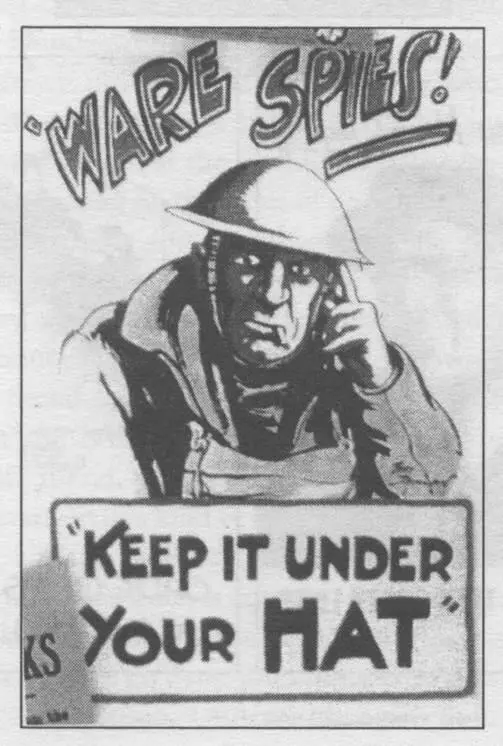

Another drawing showed an infantryman looking straight out at us: a middle-aged man (a veteran) with a cigarette between his lips and the forefinger of his left hand resting on his temple underneath his helmet, recommending us to 'Keep it under your hat', an idiom that translates into Spanish as 'De esto, ni palabra' or ' De esto no sueltes prenda' or perhaps in purer and slightly more antiquated Spanish: ' Guárdatelo para tu coleto'. And at the top, in red letters, "Ware spies!'

'Were these intended mainly for the forces, these posters?' I asked Wheeler.

'Yes, but not solely,' he replied with a slight tremor in his voice. 'That's the most interesting thing, the message wasn't intended just for soldiers, who knew more and so needed to take more care and be more discreet, but for everyone, including civilians. Look at these.' And he removed from his file a few other examples which were, indeed, not addressed to the military alone, but to the whole population.

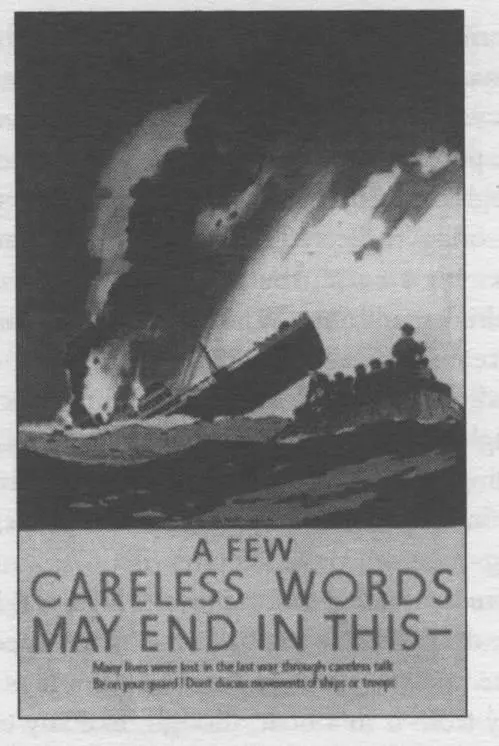

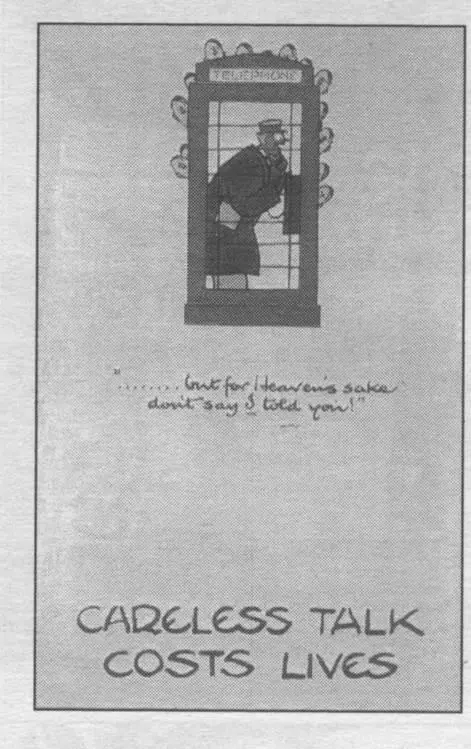

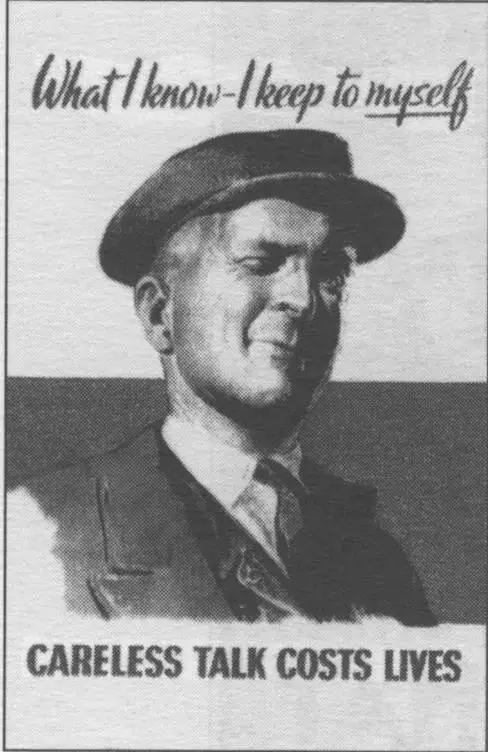

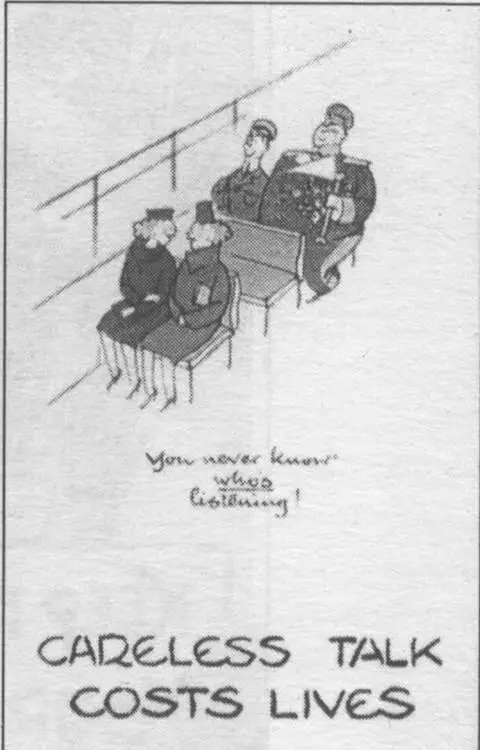

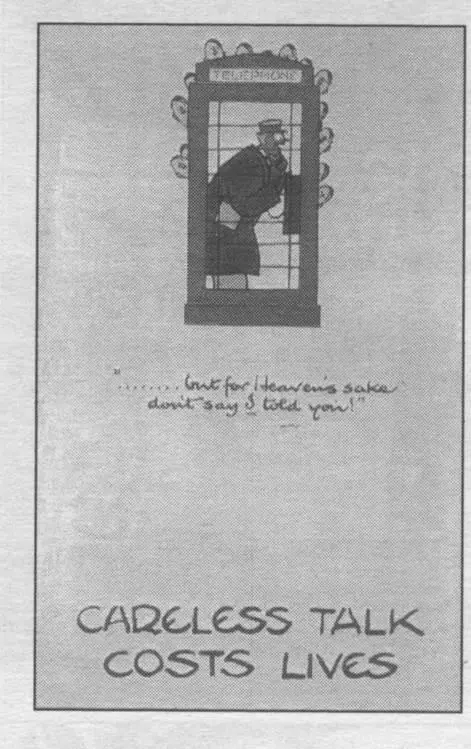

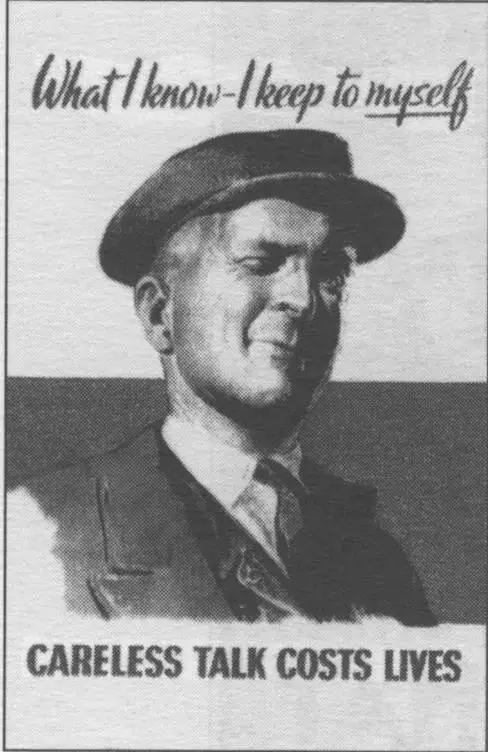

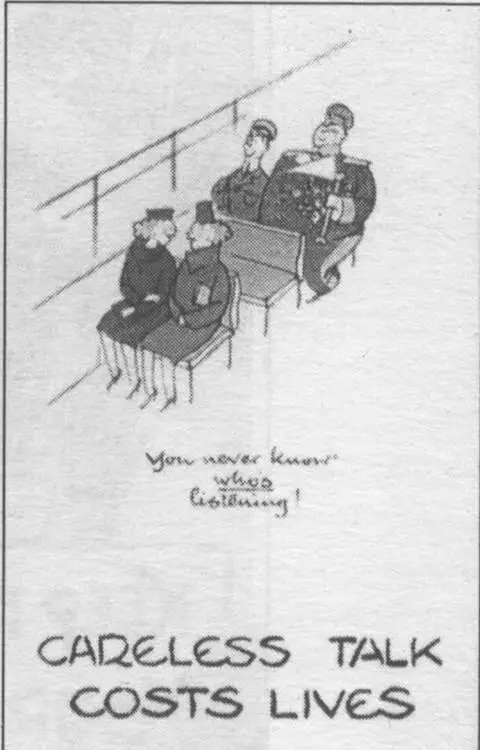

Some were cartoons. One showed a man talking on the phone inside one of those red public telephone boxes that you occasionally still see in England: according to the caption, he was saying '… but for heaven's sake, don't say I told you!', while around the walls and roof of the booth appear the cloned faces of fourteen or fifteen small Hitlers. Another showed two ladies sitting on the Underground, and one was saying to the other: 'You never know who's listening!' A couple of seats behind them sit two uniformed Nazi bigwigs, one thin, the other fat and heavily bemedalled, the former also resembled Hitler. In another poster, based perhaps on a photograph, an ordinary man wearing tie, raincoat and cap (possibly a Cockney) seemed to wink at the viewer and say: 'What I know – I keep to myself.' There were others intended to persuade children and, by imitation, to inculcate in them the importance of keeping silent ('Be like Dad, Keep Mum!'), or purely typographical official warnings with no illustration ('Thousands of lives were lost in the last war through valuable information being revealed to the enemy through careless talk. Be on your guard!'), which must have filled the noticeboards and pinboards of offices and schools and pubs and factories, as well as streets, walls, the insides of trains and buses, railway and Underground stations. Others explained, in verse, why censorship was being imposed on apparently innocuous information which, in time of peace, would have been issued without any difficulty, which would, indeed, have been mandatory, for example, the reasons for a train being delayed or stopping or arriving very late: 'In peace-time railways could explain/When fog or ice held up your train/But now the country's waging war/To tell you why's against the law…/That's because it would be news /The Germans could not fail to use.. .' (a display of consideration and public spirit, explaining to the population

Читать дальше