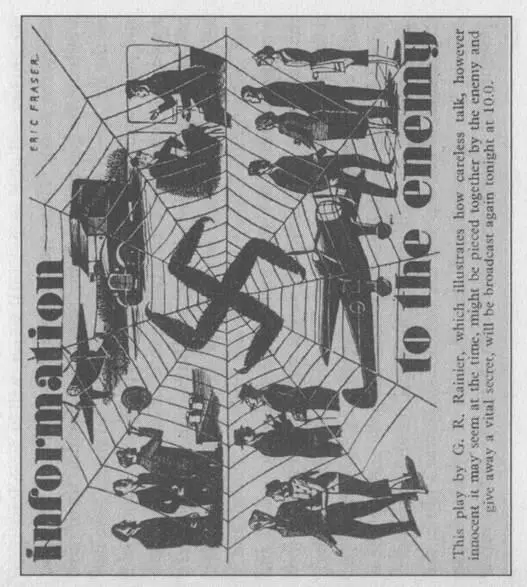

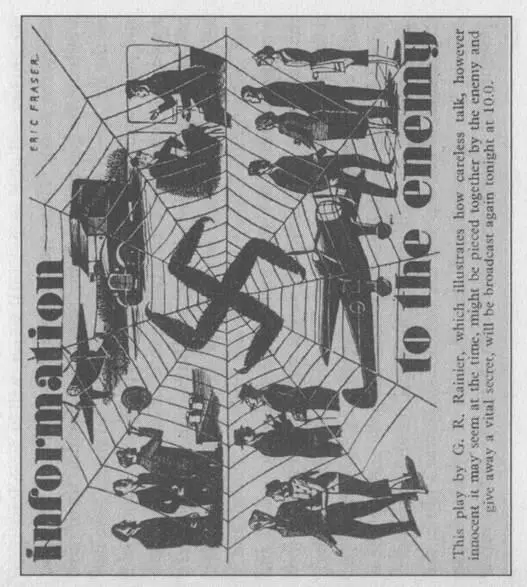

Wheeler took out of his file a yellowing newspaper cutting

showing a drawing on which the first thing that leapt out at you was the large swastika in the middle, like a hairy spider, and the web that the spider had woven, which wrapped around or, rather, trapped inside it a number of scenes. 'Information to the Enemy,' it said in large letters, the tide of a play presumably, to judge by the small print at the bottom, which said: 'This play by G. R. Rainier, which illustrates how careless talk, however innocent it may seem at the time, might be pieced together by the enemy and give away a vital secret, will be broadcast again tonight at 10.00.' There were four scenes: three men talking in a pub over a game of darts, the man lurking behind them must be the spy, given that he has a hooked nose, an artist's long hair and prissy beard, and is wearing what appears to be a monocle; a soldier is sitting on a train talking to a blonde lady, she must be the spy, not just by a process of elimination, but also given her elegant appearance; two couples are talking in the street, one composed of two men and the other of a man and a woman: the respective spies must be the man in the bow tie and the man in the scarf, although here it wasn't quite so clear (but it seemed to me that they were the ones doing the listening); lastly, a pilot is welcomed home, doubtless by his parents, and alongside them stands a young woman in apron and cap: she is clearly the spy, since she is young, an employee and an intruder. In addition, at the top and the bottom, there was a plane, the one at the top positioned very close to a mysterious van (possibly just a front) with the words 'Laundry' painted on its side.

'No, I haven't,' I said, and after carefully studying the drawing by Eric Fraser, I turned the cutting over, as I always do with old cuttings. Radio Times, 2 May 1941. It appeared to be part of the schedule for that week, for the BBC, I assumed, which, at the time, broadcast only radio. The complete tide of this didactic play by Mr Rainier (his name sounded more German than English, or perhaps he was a Monegasque) was, I saw, Fifth Column: Information to the Enemy. That expression, 'fifth column', had originated, I believe, in my city, in Madrid, which was besieged for three years by Franco and his troops and his German aviators and his Moroccan guards, and infested by his own fifth columnists, we swiftly exported both terms to other languages and other places: in May 1941, it had been a mere twenty-five months since some of us had met with defeat and others with victory, my parents were amongst the former, as was I when I was born (there are more losses amongst the vanquished and those losses last longer). Included in that radio schedule of sixty long years ago (one's eyes are always drawn to words in one's own language) was a performance by 'Don Felipe and the Cuban Caballeros, with Dorothe Morrow', they were due to be on for half an hour before the close of programming at eleven o'clock: 'Time, Big Ben: Close down'. Where would they be now, Don Felipe and the Cuban Caballeros and the inappropriately named Dorothe Morrow, presumably the vocalist? Where would they be, whether alive or dead? Who knows if they would have managed to perform that night or if they would have been prevented from doing so by a Luftwaffe bombing raid, planned and directed by fifth columnists and informers and spies from our territory. Who knows if they even survived that day.

'What about this? And this? Look at this, and this, and this.' Wheeler continued to take drawings from his file, in colour now and not originals this time, but cut out of magazines or possibly books, or else postcards and playing-cards from the Imperial War Museum in Lambeth Road and from other institutions, they must sell them now as nostalgic souvenirs or as curios, there was a whole pack of cards illustrated with them, it's odd how the useful and even essential things in one's own life become ornaments and archaeology when that life is still not yet over, I thought of Wheeler's life and thought too that I would one day see, in catalogues and in exhibitions, objects and newspapers and photographs and books whose actual creation or taking or writing I had witnessed, if I lived long enough or not even necessarily that long, everything becomes remote so quickly. That museum, the Imperial War Museum, was very close to the headquarters or head office of MI6, that is, the Secret Intelligence Service or SIS, in Vauxhall Cross, which was far from being architecturally secret, it verged, rather, on the flamboyant, on the prominent rather than the discreet, a ziggurat, a lighthouse; and it was very close to the building with no name to which I went every morning over what seemed to me a long period, even though I didn't know then that it would be for me another place of work, of which I've already had quite a few.

'Do you collect them, Peter?' I asked as I studied them. We sat for a moment on the chairs Wheeler had in his garden, they were protected by canvas or waterproof covers and arranged around a small table, he got the chairs out in early spring and took them in again in late autumn, when the days began to grow shorter, but he and Mrs Berry kept them covered up depending on what the day was like, on most days, in fact; the weather is always so changeable in England; that's why they have the expression 'as changeable as the weather', which they apply, for example, to very fickle people. We sat down directly on the canvas covers, the colour of pale gabardine, they were perfectly dry, a pause so that we could more easily sort out and arrange the drawings on the table, which was also covered, the tables and chairs disguised as modern sculptures, or tethered ghosts. There had been similar furniture in Rylands's garden, I recalled, in his nearby garden beside this same river.

'Yes, more or less, there are some things that one wants to remember as clearly as possible. Although it's more Mrs Berry who collects them, she's interested too and she goes to London more often than I do. You never think to keep the unimportant things when they occur in your own time, when they exist naturally, you think of them as easily available and assume they always will be. Later, they become real rarities, and before you know it, they're relics, you just have to see the silly things they sell at auctions nowadays, simply because they're not made any more and so they can't be found. There are collections of picture cards from forty years ago which fetch the most exorbitant prices, and the people who bid for them like mad things are usually the same ones who collected them as children and who, as young adults, threw them out or gave them away, who knows, perhaps, after a long journey, after the albums have passed through many hands, they're buying back the ones they themselves once collected and filed with such childish perseverance. It's a curse, the present, it allows us to see and appreciate almost nothing. Whoever decided that we should live in the present played a very nasty trick on us,' said Wheeler jokingly, and then showed me the drawings, his index finger trembled slightly: 'Look, you can see now what they were recommending. It's odd, isn't it, especially seen from a modern perspective, in these voracious, unrestrained times, so incapable of not asking questions or of keeping silent.'

One showed a warship sinking on the high seas in the middle of the night, doubtless having been hit by a torpedo, the sky is full of smoke and the glow of flames, and a few survivors are rowing away from it in a boat, though, like any crew member or shipwreck victim, without turning their backs on it, their gaze fixed on the disaster from which they have only half-escaped. 'A few careless words may end in this,' said the caption of what must have been a poster, or perhaps an advertisement from a magazine; and in smaller print: 'Many lives were lost in the last war through careless talk. Be on your guard! Don't discuss movements of ships or troops.' The 'last war' was the 1914-18 war, of which Wheeler retained direct, childhood memories, when he was still called Rylands.

Читать дальше