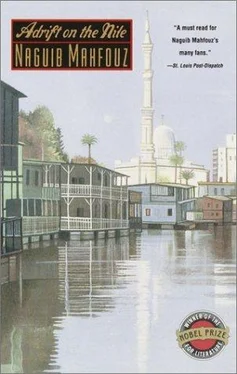

Naguib Mahfouz - Adrift on the Nile

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Naguib Mahfouz - Adrift on the Nile» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Adrift on the Nile

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Adrift on the Nile: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Adrift on the Nile»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Adrift on the Nile — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Adrift on the Nile», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

"I came back from Tahrir Square," she said, "after Ragab dropped me there."

"It's an honor, I'm sure. You can have my room if you deign to stay."

But she said, agitated: "I did not come back to sleep — as you know very well!" And then she added quietly, lowering her eyes: "I want my notebook."

"Your notebook!" he echoed, frowning.

"If you please."

The demons of malice awoke. "You are accusing me of theft!" he protested.

"No, I am not! But you came across it somehow."

"You mean that I stole it."

"I beg you, give it back to me — this is no time for talking!"

"You are mistaken."

"I am not mistaken!"

"I refuse to listen to any more of this accusation."

"I am not accusing you of anything. Give me back the notebook that I lost here."

"I don't know where it is."

"I heard you repeating what was written in it!"

"I don't understand."

"Oh yes, you do — you understand everything, and there is no reason to torment me."

"Tormenting people is not one of my hobbies."

"The night will soon be over."

"Will Mommy punish you if you get home late?" he teased her.

"Please, be serious, if only for a minute."

"But we don't know what the word means."

"Do you intend to tell everyone about it?" she asked anxiously.

"What have I to do with it, since I know nothing about it?"

"Please, be nice — I know you are, really."

"I am not 'nice.' I am half mad and half dead."

"What is written in the notebook — it's not my opinion of you — just a summary of thoughts I'm preparing for a play…"

"We're back in the world of riddles and accusations."

"I am still hoping that you will behave honorably."

"What has given you this idea, anyway?" he demanded.

"You repeated my words verbatim!"

"Don't you believe in coincidences?"

"I do believe that you will give me back my book!"

"In that case, you'd succeed in understanding in days what I have failed to in years!" And his laugh broke the silence of the void over the Nile. Then he said, in a new tone: "Your observations are inane, believe me."

"So you admit it!" she cried, gratified.

"I will give it back to you, but it will be no good for anything."

"It is nothing more than some basic ideas — they have not been developed yet."

"But you are a… vile girl."

"God forgive you…"

"You came not for friendship, but for snooping around!"

"Don't think so badly of me!" she protested. "I truly like you all, and I want to be your friend — and besides, I believe that there is a real hero in every individual. I was not interested in getting to know you just to use you in a play!"

"Don't bother to make excuses. It doesn't interest me at all, in fact."

He held out his hand to her. The notebook was in it. "As for the fifty piasters," he said. "I think I'll owe them to you."

She was perplexed. "But how?… I mean…"

"How did I steal the money? It's a terribly simple matter. We consider everything we come across on the boat to be public property!"

"I beg you — give me an explanation to set my mind at rest."

"I just couldn't resist it!" he said, laughing.

"Did you need the money?"

"Of course not. I'm not as poor as that."

"Then why did you take it?"

"I found, in spending it in the way that I did, that I could have a kind of closeness to you."

"Really, I don't understand at all."

"Neither do I."

"But I have begun to doubt my whole plan…"

"It's better that you don't have one at all." She laughed. "Except one that will lead you to the one you desire!" he went on, and she laughed again. "I understand you," he said, "just as everyone here understands you."

She was about to leave, but when he spoke she stood still, intrigued.

"You are only here because of Ragab," he said.

She laughed scornfully, but he pointed to the bedroom. "Careful not to wake the lovers."

"I am not what you think! I am a girl who…"

"If you really are a girl," he interrupted, "then come to my room and prove it!"

"How sweet you are — but you wouldn't care for me."

"Why?"

"Because it is too much if the girl is serious."

"But I only ever invite serious girls!"

"Really?"

"All the street girls are serious."

"God forgive you!"

"They don't know what absurdity is. They work until the crack of dawn, and there's no fun or pleasure in it. But they have a truly progressive aim — and that is to lead better lives!"

"Shame on you all! None of you can tell the difference between seriousness and frivolity!"

"Seriousness and frivolity are two names for the same thing."

She sighed, indicating that she was about to depart, but hesitated for a moment. "Will you tell the others about the notebook?" she asked.

"If that were my intention, I would have done it."

"I beg you, by all that is dear, tell me frankly what you have in mind."

"I have."

"I would prefer simply to disappear rather than be driven away."

"I do not want either to happen."

They shook hands in farewell. "Thank you," she said, like a close friend.

As she hurried away, the voice of Amm Abduh rang out, giving the call to the dawn prayer.

13

The houseboat rocked; someone was coming. Since the party was already complete, they wondered who it could be, and looked toward the door with a certain anxiety. Ahmad rose in order to stop the newcomer at the door, but a familiar laugh was heard, and then Sana's voice, calling: "Hello!" She came in, bringing by the hand a well-dressed young man. Ragab stood up to welcome him, saying: "Good evening, Ra'uf!" and introduced him to the others as "the well-known film star…" The couple sat down amidst lukewarm and formal expressions of greeting.

Sana said, in a voice that was bolder than usual: "He gave me so much trouble before he finally agreed to come! He said: "How can we intrude on their privacy?"' But he is my fiancé — and you are all my family!"

She received congratulations from all the group, and continued: "And like you, he's one of those!" — pointing at the water pipe and laughing. Her breath smelled of drink. Anis felt no embarrassment, and vigorously sent the pipe on its rounds. "Aren't you lucky, Ra'uf," Sana said next. "Here is the great critic Ali al-Sayyid, and the famous writer Samara Bahgat — the pipe makes strange bedfellows!"

"But Samara, unfortunately, does not partake," said Ragab.

"Why does she keep on coming, then!" Sana replied scornfully.

Ra'uf whispered a few words in her ear that were unintelligible to anyone else; she only giggled. Then Amm Abduh came in to change the water in the pipe, and when he had gone, Sana said to Ra'uf: "Can you believe that all that great hulk is one man?" And she laughed again, but this time alone. There followed a tense silence that lasted a quarter of an hour. Finally Ra'uf prevailed upon her to leave with him. Taking her by the arm, he stood up. "My apologies," he said. "We must go — we have an urgent appointment. I am very happy to have met you all…"

Ragab accompanied them to the door, and then returned to his seat. They remained gloomy in spite of the water pipe passing from hand to hand. Ragab smiled at Samara to humor her, but she only said, indicating the pipe and alluding to Sana's scornful remark, "Whatever I say, no one believes me."

"It doesn't disgrace you totally to have people say that," said Layla.

"Except when those people are my enemies."

"You have no enemies," said Ragab simply, "except the fossilized remnants of the bourgeoisie."

But she began to talk about the rumors that were spreading among her journalist colleagues, and she mentioned also her former flat in al-Manyal, where her late homecomings had set the neighbors to gossiping. "And when my mother said: "Her job keeps her out late," they said: "Well, what keeps her at her job!"

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Adrift on the Nile»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Adrift on the Nile» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Adrift on the Nile» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.