Naguib Mahfouz - Adrift on the Nile

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Naguib Mahfouz - Adrift on the Nile» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

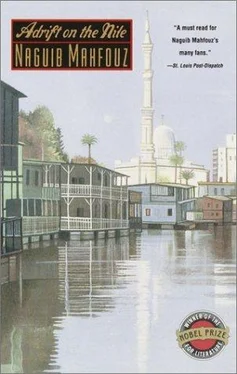

- Название:Adrift on the Nile

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Adrift on the Nile: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Adrift on the Nile»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Adrift on the Nile — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Adrift on the Nile», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Naguib Mahfouz

Adrift on the Nile

Adrift on the Nile

1

April. Month of dust and lies. The long, high-ceilinged office a gloomy storeroom for cigarette smoke. On the shelves the files enjoy an easeful death. How diverting they must find the civil servant at work, carrying out, with utterly serious mien, utterly trivial tasks. Recording the arrival of registered post. Filing. Incoming mail. Outgoing mail. Ants, cockroaches, and spiders, and the smell of dust stealing in through the closed windows.

"Have you finished that report?" the Head of Department asked.

Anis Zaki replied indolently. "Yes," he said. "I've sent it to the Director General."

The Head gave him a piercing look that glinted glassily, like a beam of light, through his thick spectacles. Had he caught Anis grinning like an imbecile at nothing? But people were used to putting up with such nonsense in April, month of dust and lies.

The Head of Department began to be overtaken by an odd, involuntary movement. It spread through all the parts of his body that could be seen above the desk — slow and undulating, but visibly progressing. Gradually, he began to swell up. The swelling spread from his chest to his neck, to his face, and then over his entire head. Anis stared fixedly at his boss as the swelling obliterated the features and contours of his face and finally turned the man into a great globe of flesh. It appeared that he had grown lighter in some astonishing way, for the globe proceeded to rise, slowly at first, and then gradually more swiftly, until it flew up like a gas balloon and stuck, bobbing, to the ceiling…

"Why are you looking at the ceiling, Mr. Zaki?" the Head of Department asked.

Caught again. Eyes stared at him in pitying mockery. Heads were shaken regretfully in ostentatious sympathy for the boss. Let the stars bear witness to that! Even the midges and the frogs have better manners. The asp itself did the Queen of Egypt a great favor. But you, my colleagues? There is no good in you; my only comfort lies in the words of that dear friend who said: "Come and live on the houseboat. You won't have to pay a millieme. Just get everything ready for us."

With sudden resolution he began to deal with a pile of letters. Dear Sir: With reference to your letter reference number 1911, dated February 2, 1964, and to the communication pertaining, reference number 2008, dated March 28, 1964: I have the honor of informing you… Filtering in along with the smell of dust, a song from a radio in the street: "Mama, the moon is at the door." He paused, pen in hand, and muttered: "Wonderful!"

"Lucky you, with no worries," said a colleague on his right.

Damn the lot of you. Timeservers every one. Waiting for a dream that will never come true, you turn your silly tricks. I am the only miracle here, speeding — without a rocket — into outer space…

The office boy came in. Anis felt his stomach rumble, and asked for one coffee, no sugar.

"You'll find it on your desk," the office boy replied, "when you come back from seeing the Director General." And so Anis, tall and big — heavy-boned, though, not fat — left the room.

Once in the Director General's office, he stood meekly in front of the desk. The Director's bald head remained bowed over the papers he was perusing, looking to Anis like an upturned boat… With his last scrap of willpower Anis drove away such distracting thoughts. Distraction at this point would have the most dire consequences.

The man lifted his lined, angular face to fix Anis with a bristling glare. What error could have crept into the report that he had taken such pains to compile?

"I asked you to write a detailed report on the movement of incoming correspondence for last month," the Director said.

"Yes, sir, and I've presented it to you, sir."

"Is this it?"

Anis glanced at the report. On the cover he read, in his own handwriting: _Report on Incoming Correspondence for the month of March — for the attention of the Director General of the Archives Department._

"That's it, sir."

"Look at it and read it."

He saw one line, clearly written, followed by a blank space. Dumbfounded, he turned over the remaining pages. Then he gaped like an imbecile at the Director General.

"Read it!" the man said angrily.

"Sir — I wrote it out word for word…"

"Would you care to tell me how it has vanished?"

"Really, it's a complete mystery to me!.."

"But you _can_ see before you the marks made by the pen nib?"

"Marks made by the pen nib…?"

"Give me this magic pen of yours!" the Director said, and, brusquely taking the pen from Anis, he began to score lines on the cover of the report. None of the lines came out on the paper. "There isn't a single drop of ink in it!" said the Director.

Consternation spread over Anis' broad face.

"You began writing this line here, and then the ink ran out," the Director continued caustically. "But you carried on!"

Anis said nothing.

"You failed to notice that the pen was not writing!"

Anis made a perplexed gesture.

"Can you tell me, Mr. Zaki, how this could have happened?"

How indeed. How did life first creep into the mosses in the cracks of the rocks, in the ocean depths?

"You're not blind, as far as I'm aware, Mr. Zaki."

Anis hung his head.

"I shall answer for you. You did not see what was on the page, because you were… drugged!"

"Sir!"

"It's the truth. And a truth which is known, furthermore, to everyone right down to the office boys and porters. I am not a preacher. Nor am I responsible for your well-being. You may do with yourself as you please. But I have the right to demand that you refrain from doping yourself during working hours."

"Sir!"

"Enough sir-ing and demurring. Be so good as to comply with my humble request and leave your habit at home."

Anis protested. "As God is my witness — I am ill!"

"The eternal invalid, that is what you are."

"Don't believe what…"

"I only have to look into your eyes!"

"It's illness — nothing else!"

"All I can see is that your eyes are red, cloudy, heavy…"

"Don't listen to talk!.."

"… and they look inward, instead of outward like the rest of God's creatures!"

The Director's hands, covered with bushy white hairs, made a threatening gesture.

Sharply, he said: "There are limits to my patience. But there is no end to a slippery slope. Do not tumble down it. You are in your forties, which should be a time of maturity. So stop this tomfoolery."

Anis took two steps backward, preparing to leave.

"I shall only cut two days' pay from your salary," the man added. "But beware of any repetition of this episode."

As he moved toward the door, Anis heard the Director General say contemptuously: "When will you learn the difference between a government department and a smoking den?"

On his return to the department, heads were raised and turned inquisitively in his direction. Ignoring them, he sat down and gazed at his cup of coffee. He became aware of a colleague leaning over to him, no doubt to ask him all about it. "Mind your own business," he muttered angrily.

He took an inkwell out of the drawer and began to fill his pen. He would have to rewrite the report. "Movement of Incoming Correspondence." It was not a movement at all, really. It was a revolution around a fixed axis, round and round, distracted by its own futility. Round and round it went, and the only thing that came of it was an endless revolution. And in the whirling giddiness everything of value disappeared: medicine and science and law, family forgotten back home in the village, a wife and small daughter lying under the earth. Words once blazing with zeal now buried under a mountain of ice…

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Adrift on the Nile»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Adrift on the Nile» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Adrift on the Nile» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.