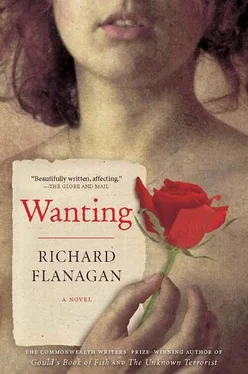

Though, on arriving in Hobart, she had soon acquired an extensive wardrobe of cuts and colours, Mathinna’s inevitable preference was for red. Nothing had caught her fancy like the red dress that Lady Jane had herself worn as a child, and which she had given Mathinna as a present on the first anniversary of her arrival. Button-shouldered and short-sleeved, belted with a black velvet band, the red dress was made of the lightest silk and cut in the simple high-waisted style popular in the wake of the French Revolution, when anything more elaborate was deemed aristocratic decadence.

Mathinna was at the far end of the main gravel path, playing with her cockatoo, sprinkling water over its awkwardly outstretched wings as it strutted around a fountain like an old drunk. As the bird waddled, Mathinna danced, a strange dance, where at times her own body seemed to be floating. As they came closer, Sir John realised that she was singing in her own strange yet strangely incantatory tongue.

Until that day he hadn’t really noticed Mathinna, viewing her as one more in a very long series of his wife’s enthusiasms, best endured like wind and snow, silently and stoically. That day, though, he saw her as if for the first time. Only now, as they walked towards her, did Sir John notice her eyes, which so many others had commented on. They seemed the largest and darkest eyes imaginable. And though only very occasionally and only after considerable encouragement and admonition could they be properly glimpsed, he understood why they were so much admired. She had learnt the odd art of playing the coquette, which she regarded as simply a different animal dance.

Only now, as they continued on past her, did Sir John finally realise she was, as Montague put it admiringly—and he was from the beginning anything but an admirer—the most beautiful savage he had ever seen. But it wasn’t her looks—neither Nubian nor of the Levant, but something else again—that first enchanted Sir John. It was the way she smiled at him.

It was true, as he told Lady Jane over dinner, that it was ‘the contrast of that wild beauty with the civilised dress of the Age of Reason’ he found delightful, but it was the sudden, unexpected flashing gleam of teeth that disarmed him. Gleam of teeth, swirl of red, puddle of eye, dance of feet. Sir John had been everywhere—but he had never seen anything like her. He felt as if he had just awoken.

On the day the glyptotech opened, Lady Jane looked up at the wild mountain, its snowy peak lost in mist, and then back at the sandstone Greek temple that now sat at the head of that picturesque forested valley. Once, perhaps, she thought, Zeus did sport here, transforming into whatever animal he needed to be—a bull, a goat, a swan—in order to take yet another mortal or goddess unawares. At that moment a kangaroo came bounding across the temple. As its rising and falling body linked the Corinthian columns at the front of the temple with sweeping arcs of flight, Lady Jane laughed at her absurd fantasy.

Mathinna stood with Lady Jane and the official party, but her status was changing. Less and less was she the Franklins’ adopted daughter, and more and more was she some other creature whom they came to regard as they did several other pets around Government House—the albino possum, her cockatoo, a wombat—an exotic object of amusement.

Sir John had begun to seek Mathinna out and have her sing songs in her native tongue; then, as he got to know her better, he had her dance the kangaroo dance and the possum dance, the echidna dance and the emu dance, but the one he particularly enjoyed was the black swan dance, in which she would jack-knife her body backward and jolt her arms forward and out, as if rising into flight.

Those who wished to enter the Franklins’ circle had to acknowledge Mathinna, had to profess themselves amused and charmed by the black girl. She took pleasure in her status, demanding curtsies from all, and she now castigated the servants, whom she had once been too shy even to look in the eye, for not satisfying her whims.

And when, that day of the opening of Ancanthe, as the glyptotech was named, Mathinna’s cockatoo flew onto Montague’s shoulder and left a wet, white dropping trailing down his black coat, not even Sir John’s assurance that such things were good luck could drown out the laughter of the black girl, so raucous and uninhibited that it infected the whole party until they were all laughing.

A humiliated Montague whispered to his wife that the child behaved not like a lady, but some wild thing. And he pointed to the ground, where they could see her naked toes forking their way in and out of the mud.

‘Like filthy grubs and worms,’ sneered Montague. ‘It is as if dirt itself were a pleasure.’

The more Mathinna stopped being what the Franklins expected and the more she became herself, the more the Governor grew to like her. He was fascinated by ‘the forest sprite’, as he called her, both because of her general liveliness and her particular ability to appear out of nowhere and startle people: none more so than Lady Jane, who found it a trait at first amusing, then slightly disturbing and finally immensely irritating—for what exactly had the child heard, and what had she seen? And what did she know, what did she think, that smiling black enigma?

Lady Jane would feel something wrapping around her and look down to see black arms around her waist. She would twist and stride off, and Mathinna, sensing it was a game, would take two skips to join her and, with a cry of glee, again wrap her arms around Lady Jane’s legs. Lady Jane could smell her then, that wild, dangerous, dog smell of children. Once more she would push the child away, yet still Mathinna would persist and reach out, seeking to grab one of Lady Jane’s skirt-clad thighs.

‘Please, Mathinna,’ Lady Jane would say softly, grabbing her wrist harshly. ‘ Please . I don’t like that.’

Nor, said Sir John, did he. But secretly he began to crave such touch and warmth. He loved the way Mathinna moved, so quick and alive. He watched entranced as, one afternoon, she made traps for the seagulls that plagued the port town—a simple affair of a piece of bread at the end of a long string, which with infinite patience she drew towards a cairn made of twisted branches and bark, behind which she waited and, when the moment was right, grabbed the bird in a single lightning-like movement. He spent the rest of the day playing this game with her, ignoring Montague’s occasional interruptions that he was late for this appointment or that meeting, until he finally managed to draw the seagull into the trap; but he was so slow lunging after it that the bird was in flight and Mathinna laughing before he had finished falling.

Sir John could not forget that laugh. Under his breath he boxed the compass, reciting in perfect order the sailors’ catechism: ‘North—North by east—Northeast by north’, the thirty-two points of order that summoned home’s certainty out of an oceanic emptiness. ‘Northeast—Northeast by east—East-northeast,’ he would mumble to forget that laughter’s enticing sound.

But he was south of no north now, and every compass point served only to concentrate his thoughts more powerfully upon her. For whether it was west by northwest or south-southeast, she was everywhere. And when he resorted to naming the winds and their origins, still it did no good, for Lady Jane had insisted that Mathinna should have a bell tied around her wrist so that they might know where she was, so that her presence would not frighten Lady Jane or the various dignitaries visiting Government House, and to ensure that the ‘empty black vessel’, as Lady Jane began calling her, ‘will not fill with any more indiscretions’. And just naming the Sirocco of the Southeast or the Mistral of the Northwest was enough to bring to Sir John’s ears the sound of that tinkling.

Читать дальше