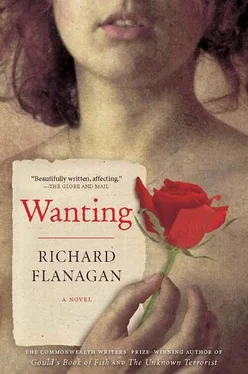

You see, reason, gentlemen, is a fine thing, that is unquestionable, but reason is only reason and satisfies only man’s reasoning capacity, while wanting is a manifestation of the whole of life.

Fyodor Dostoevsky

That which is wanting cannot be numbered.

Ecclesiastes

THE WAR HAD ENDED as wars sometimes do, unexpectedly. A man no one much cared for, a rather pumped-up little Presbyterian carpenter cum preacher, had travelled unarmed and in the company of tame blacks through the great wild lands of the island, and had returned with a motley cluster of savages. They were called wild blacks, though wild they most certainly were not, but rather scabby, miserable and often consumptive. They were, he said—and remarkably it did now seem—all that remained of the once feared Van Diemonian tribes that for so long had waged relentless and terrible war.

Those who saw them said it was hard to believe that such a small and wretched bunch could have defied the might of the Empire for so long, that they could have survived the pitiless extermination, that they could have been the instruments of such fear and terror. It wasn’t clear what the preacher had said to the blacks, or what the blacks thought he was going to do with them, but they seemed amenable, if somewhat sad, as broken party after broken party were embarked on boat after boat and taken to a distant island that lay in the hundreds of miles of sea that separated Van Diemen’s Land from the Australian mainland. Here the preacher took on the official title of Protector and a salary of £500 a year, along with a small garrison of soldiers and a Catechist, and set about raising his sable charges to the level of English civilisation.

He met with some successes, and, though these were small, it was on such he tried to concentrate. And were they not worthy? Were his people not knowledgeable of God and Jesus, as was evidenced by their ready and keen answers to the Catechist’s questions, and evinced in their enthusiastic hymn-singing? Did they not take keenly to the weekly market, where they traded skins and shell necklaces for beads and tobacco and the like? Other than that his black brethren kept dying almost daily, it had to be admitted the settlement was satisfactory in every way.

Some things, however, were frankly perplexing. Though he was weaning them off their native diet of berries and plants and shellfish and game, and onto flour and sugar and tea, their health seemed in no way comparable to what it had been. And the more they took to English blankets and heavy English clothes, abandoning their licentious nakedness, the more they coughed and spluttered and died. And the more they died, the more they wanted to cast off their English clothes and stop eating their English food and move out of their English homes, which they said were filled with the Devil, and return to the pleasures of the hunt of a day and the open fire of a night.

It was 1839. The first photograph of a man was taken, Abd al-Qadir declared a jihad against the French, and Charles Dickens was rising to greater fame with a novel called Oliver Twist . It was, thought the Protector as he closed the ledger after another post mortem report and returned to preparing notes for his pneumatics lecture, inexplicable.

ON HEARING THE NEWS of the child’s death from a servant who had rushed from Charles Dickens’ home, John Forster had not hesitated—hesitation was a sign of a failure of character, and his own character did not permit failure. Mastiff-faced, full-bodied and goose-bellied, heavy in all things—opinion, sensibility, morality and conversation—Forster was to Dickens as gravity to a balloonist. Though not above mimicking him in private, Dickens was immensely fond of his unofficial secretary, on whom he relied for all manner of work and advice.

And Forster, inordinately proud of being so relied on, decided he would wait until Dickens had given his speech. In spite of Forster’s ongoing arguments that recent events excused Dickens from the necessity of addressing the General Theatrical Fund, he had been unwavering that he would. Why, even that very day Forster had called on Dickens at Devonshire Terrace to urge him one last time to cancel the engagement.

‘But I’ve promised,’ said Dickens, whom Forster had found in the garden playing with his younger children. He had in his arms his ninth child, the baby Dora, and he’d lifted her above his head, smiling up at her and blowing through his lips as she beat her arms up and down, fierce and solemn as a regimental drummer. ‘No, no; I could not let us down like that.’

Forster had swelled, but said nothing. Us! He knew Dickens sometimes thought of himself more as an actor than a writer. It was a nonsense, but it was him. Dickens loved theatre. He loved everything to do with that world of make-believe, where the moon might be summoned down with a flourish of a finger, and Forster knew Dickens felt a strange solidarity with the actor members of the troupers’ charity, which he was to address that evening. This attraction to the more disreputable both slightly troubled and slightly thrilled Forster.

‘She looks well, don’t you think?’ Dickens had said, lowering the baby to his chest. ‘She’s had a slight fever today, haven’t you, Dora?’ He kissed her forehead. ‘But I think she’s picking up now.’

And now, only a few short hours later, how splendidly Dickens’ speech was going, thought Forster. The crowd was extensive, its attention rapt, and Dickens, once started, as brilliant and moving as ever.

‘In our Fund,’ Dickens was saying to the crowded hall of actors, ‘the word exclusiveness is not known. We include every actor, whether he is Hamlet or Benedict: this ghost, that bandit, or, in his one person, the whole King’s army. And to play their parts before us, these actors come from scenes of sickness, of suffering, aye, even of death itself. Yet—’

There was a stuttering of applause that stopped almost before it started, perhaps because it was felt bad taste to draw attention to Dickens’ being there just two weeks after his own father’s death. A failed operation for bladder stones had left the old man, Dickens had told Forster, lying in a slaughterhouse of blood.

‘Yet how often it is,’ continued Dickens, ‘that we have to do violence to our feelings, and hide our hearts in carrying on this fight of life, so we can bravely discharge our duties and responsibilities.’

After, Forster took Dickens aside.

‘I am afraid…’ Forster began. ‘In a word,’ said Forster, who always used too many, but now realised there was one he did not wish to utter.

‘Yes?’ said Dickens, eyeing somebody or something over Forster’s shoulder, then looking back, eyes twinkling. ‘Yes, my dear Mammoth?’

His casual use of Forster’s nickname, his presumption all this was just banter, the pleasure of the performer at the success of a performance—none of it helped make poor Forster’s task any easier.

‘Little Dora…’ said Forster. His lips twitched as he tried to finish the sentence.

‘Dora?’

‘I am,’ mumbled Forster, wishing at that moment to say so many things, but unable to say any of them. ‘I am, so, so sorry, Charles,’ he said in a rush, regretting every word, wanting something so much better to say, his hand rising to emphasise with its customary flourish some point never made, then falling back to the side of his body, his big body that felt so bloated and useless. ‘She was taken with convulsions,’ he said finally.

Dickens’ face showed no emotion, and Forster thought what a splendid man he was.

Читать дальше