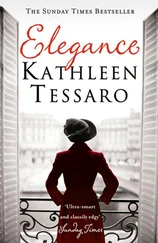

‘A prude? Well, no. I don’t think so,’ Grace fumbled, offended.

‘I only ask because this is not a fairy tale, my dear.’ Taking out a long black cigarette holder, Madame Zed fitted a cigarette into it and lit it. She looked across at Grace, staring at her from beneath her heavily lidded dark eyes. ‘You came to me. You wanted to know more. But I can’t change the story to put you at ease.’

‘No. I don’t want you to do that,’ Grace relented. ‘I just suppose it’s a bit shocking that she would go off with a… a grown man like Lambert.’

Madame exhaled. ‘Lambert took her to Europe, introduced her into society, gave her an education of sorts. Some of us, no matter how hard we try, aren’t meant to lead ordinary lives. Fate finds us. Gives us a shove.’ She drew the holder to her lips and inhaled slowly. ‘Fate has given you a little push, hasn’t it?’

‘Me?’

Madame nodded. ‘Here you are, in a foreign city, with a strange legacy.’ She exhaled through her nose. ‘Perhaps, Madam Munroe, you weren’t meant for a mundane life either. Perhaps you’re considerably more exciting than you realize.’

‘Me? Oh no, I’m as dull as ditchwater.’

‘Really?’ Madame tilted her head to one side. ‘Tell me, where did you grow up again?’

‘In Oxfordshire. A small village called West Challow.’

‘And you lost your family in the war?’

‘My mother died in the Blitz. But my father died before the war, of a heart attack.’

‘Yes, I remember now,’ she nodded to herself. ‘You told me that. And what was she like, your mother?’

‘My mother?’ Grace frowned, laughing a little. She hadn’t expected to be the topic of conversation between them. ‘Well, let’s see…’ She tried to concentrate. ‘She was small, very energetic and had that kind of deep auburn hair I’ve always wanted myself but wasn’t lucky enough to inherit.’ She smiled to herself. ‘She seemed very beautiful and charming to me. She was also the author of several rather badly written romantic novels published under the pen name Irene Worthing.’

‘Really?’ Madame seemed fascinated. ‘How extraordinary. Have you read them?’

‘Of course. A thousand times.’

‘What about your father?’

‘It’s difficult for me to remember him at all, to be honest. He was a botanist. He came back a hero from the Great War… he was quite deaf from all the shelling and had suffered terribly from mustard gas poisoning. He was unable to be comfortable for any period of time.’

‘Do you miss them?’

Grace looked across at her. It was an odd thing to ask.

‘It’s been so long,’ she said after while. ‘At least, I think I miss the idea of them. I have to admit that I’ve forgotten almost everything about them or it’s been distorted. For example, my mother used to smell a certain way – of rose-water perhaps, or of soap, I can’t remember which. I don’t know if she smelled like that all the time or just once.’ She paused. ‘We lived on my mother’s family estate. But we didn’t live in the Great Hall – we had a smaller, separate house on the grounds where my father could work on his research as a botanist. He was always brooding, distracted. He didn’t speak much because of his hearing. I think he was actually extremely shy. He drew a lot, took notes. He preferred to make things.’

Madame inhaled slowly. ‘Like what?’

‘He made a three-storey house for the hens that was heated by a row of light bulbs under a wire mesh floor in the winter and that was always perfectly snug.’

‘How funny!’

‘Yes,’ Grace smiled. ‘And he built my mother a series of rotating pantry shelves and a wringer for the laundry that was operated by using a pedal on the floor rather than a handle so her arms wouldn’t grow tired.’

‘Did she like that?’

‘Well, she wasn’t very domestic – not much of a cook. She was more involved with her writing. Besides, we always had help for the housekeeping duties. They must have liked his inventions. But my father liked solving problems, I think, and my mother let him. I don’t think… I’m sorry.’ Suddenly Grace found it hard to concentrate on what she was trying to say. ‘I think something’s burning, isn’t it?’

‘What?’

‘Have you got something in the oven? Your supper? I think it must be burning.’

‘Oh, merde ! Not again!’ Crushing her cigarette into the ashtray, Madame got up and hurried to the kitchen. Grace could hear her muttering and cursing, the banging of pots and pans, the sound of running water.

When she didn’t return after a few minutes, Grace ventured into the hallway. The smell of charred pastry crust filled the corridor. ‘Can you save it?’ she asked, doubtfully.

‘It’s nothing.’ Madame opened the kitchen window to clear the smoke out. ‘Nothing that can’t be made again another time. I have always abhorred cooking. But every once in a while I try.’

‘I’m a dreadful cook. Far too easily distracted. I suppose I get that from my mother.’

Madame gave her a curious look. ‘Perhaps you do. But you must forgive me,’ she began ushering Grace towards the door, ‘it’s late. And as you can see, I have some cleaning to do.’ She held the door open for her. ‘Come again. Maybe tomorrow. And we will talk some more.’

Grace lit a cigarette on the pavement outside the deserted perfume shop on Rue Christine and began walking back to her hotel through the quiet, dimly lit streets, recounting Madame’s words. One sentence echoed in her mind, replaying itself over and over.

‘A young woman on the cusp of her sexual awakening is a powerful creature.’

She took a deep drag. Here in this strange city, the net of her memory loosened. She too had been intoxicated by her awakening sexuality.

It had happened just as Madame had noted; early on; after her mother’s death when she was thirteen or so. She’d only recently gone to live with her uncle in Oxford. He had no experience with children; suddenly she found she had the run of the house. He was always working and she was left more and more to her own devices, treated as an adult rather than a child. Grace remembered feeling such a tangle of opposing emotions – the aching loss of her mother, fear, and at the same time a new confidence and terrible, thrilling freedom. But underneath all that, there was an unfamiliar, overwhelming desire to be touched. Her body had grown languid, easily aroused. And overnight it had transformed from the narrow shapeless body of a child to that of a young woman, with a slimmer waist, swelling breasts, curving hips.

She began attracting attention. Clandestine looks and mysterious tensions suddenly corseted her days; unspoken invitations tugged at her awareness. Her uncle, always on the periphery, receded even further, maintaining a respectful distance from her transformation. But his colleagues gazed upon her with new eyes and suddenly she too had moved a little slower, a little more deliberately, teasing out their interest without knowing why; simply because all of a sudden she could.

She was fascinated and repulsed in equal measures by the sudden increase in male attention. She learned to cover her desire with a steely surface of indifference, playing the tensions off one another.

It had been an effective strategy, surprisingly sophisticated for one so young.

Near the banks of the Seine, tucked beneath bridges, in the shadows, Grace glimpsed the outlines of couples, bodies entwined, stealing embraces.

She crossed over the river, the black water rushing beneath her like a sheet of moving glass, the lights from the shore reflected in its smooth surface.

There had been a student of her uncle’s, a young man in his early twenties named Theo Lund; lanky, serious, with large, round blue eyes. He was shy, studious, socially awkward. From a modest background, he didn’t mix much, but was instead dedicated to earning his degree.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу