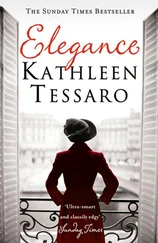

‘Yes,’ Madame continued. ‘We try and fail, like archers who aim for the target but fall short of the mark.’ Eva watched as she removed the lace shawl. ‘When you are older and have swum out into the stream of life, you’ll see – there are no “good” people, little girl. We’re all trying and failing, trying too hard and failing too often. Remember that. We shouldn’t judge too harshly, in the end, the sins of others.’

‘No, madam. Of course not.’

Eva wasn’t sure she’d answered her question.

But the older woman sank down into the armchair, stretching her legs out on the ottoman. She took another drag of her cigarette. Her voice softened to almost a whisper. ‘Sometimes I think the only things we have in common with one another are our shortcomings’

Eva stood enthralled.

Exhaling a long stream of smoke, Madame closed her eyes and her head lolled to one side.

Eva waited for her to continue.

Madame’s hand relaxed.

The cigarette fell to the floor.

Eva rushed to put it out before it burned a hole in the carpet.

Then Madame began to snore, so loudly that Valmont came in.

‘Oh. It’s you,’ he said, jamming his hands sullenly into his pockets. ‘I should’ve known.’

Eva planted her hands on her hips. ‘What’s that supposed to mean?’

He ignored her question. ‘Jesus! She’s been to Chinatown again. Help me get her on to the bed,’ he ordered, lifting Madame up under her arms.

Begrudgingly, Eva grabbed her legs. ‘Goodness!’ she gasped. ‘She weighs a lot for someone so skinny!’

Together they hauled her onto the bed. Madame didn’t even so much as miss a beat in her snoring and rolled over heavily on to her side.

‘I’ve never heard anyone so loud.’

‘It is a bit much,’ Valmont admitted. ‘It goes right through the door at night. I sleep with about four pillows on my head. She’ll be passed out for the rest of the day now.’

‘She doesn’t smell drunk.’

He rolled his eyes. ‘Don’t you know anything? Opium,’ he explained. ‘She’s been smoking opium.’

‘Oh.’ Eva stared in awe at the sleeping woman. An opium den. How dreadful, low and exciting.

‘We’re going to Morocco soon and it will only get worse.’

‘Morocco? What are you going to do there?’

‘We’re buying ingredients. They have, among other things, one of the finest jasmine harvests in all the world. Normally we buy them through a third party but I’m sure if we go there ourselves we’ll discover not only purer absolutes for a better price, but I have a feeling we’ll also stumble across some rare indigenous ingredients we haven’t encountered yet in Europe. And that’s what we’re looking for – a new palette, something truly original.’

Eva smiled to herself, gathering her duster from the dressing table.

‘Why are you sneering at me?’ he demanded.

‘I’m not sneering.’

‘Yes, you are.’

‘You always talk like you’re in charge,’ she pointed out.

‘Well, I do have influence. She values my opinion. She’s one of the world’s greatest perfumers and I am, after all, her only apprentice.’

‘So you keep saying – over and over again. Besides, I thought you were her secretary.’

‘I’m more than that. You see,’ he followed her into the bathroom, leaned against the doorway, ‘you can’t go to school to learn the art of the perfumer. You have to possess a natural, God-given talent and then the secrets of the profession must be passed on by a master. I have been an apprentice to Madame since I was nine.’

‘Nine? How old are you now?’

‘Eighteen.’

She snorted. ‘Are you a slow learner?’

‘It’s an art!’ He glared at her. ‘It takes years just to memorize the various ingredients. It isn’t just about mixing notes together but about developing a palette, a comprehension of scent and how it works. Do you have any idea of how difficult it is to create a fragrance that develops properly on the human skin and lasts?’

Eva folded her arms defensively across her chest. ‘So how did Madame know you had talent in the first place?’

‘I suppose she could just tell.’ This girl really asked the most presumptuous questions. ‘Actually, even when I was small I could dissect smells, take them apart and decipher their precise ingredients. There is a story that Madame discovered me one day standing in the neighbour’s garden, standing over a rosemary bush. Apparently I was so lost in concentration, I couldn’t hear my name being called. It was by far the nicest-smelling thing in the whole village,’ he recalled.

‘And your parents just gave you to her?’

‘No! Of course not!’ he snapped.

‘I’m only asking!’ she snapped back. ‘Did they pay her?’

‘They don’t have that kind of money. My parents came from Prussia. They’d escaped, during the Revolution, with nothing but what they could carry. My father was a cantor.’

‘A what?’

‘A cantor,’ he repeated, his cheeks colouring a little. ‘It’s a singer of religious songs in the Jewish temple.’

‘Oh.’ She’d never actually spoken to anyone Jewish.

‘It’s a sacred profession – a vocation really – that’s been passed down through generations,’ he continued. ‘I suppose they thought I might follow my father one day. But my parents couldn’t afford to keep all of us – my brothers and sisters are younger than me. And cantors don’t make much money. For a while I lived with some neighbours down the street. I suppose they were nice enough. Tailors. I used to press the garments, deliver orders and clean the work room to earn my keep.’

‘How old were you?’

‘I’m not sure… six or seven. And then Madame came along, looking for an assistant – someone she could train. Her offer was a rare opportunity.’

‘Still, it’s quite young.’ Eva’s voice softened. ‘Did you ever seen them again – your parents?’

He shook his head. ‘You must miss them.’

‘Oh, I don’t know. I never really think about it.’

Eva wasn’t fooled. ‘My mother died when I was born, back in Lille,’ she said. ‘My aunt and uncle brought me here. But they didn’t really want me. It’s funny, isn’t it? How you can miss someone you’ve never known.’

‘I suppose.’

Eva adjusted the tin bucket and mop on the side of her cart. ‘I sometimes wonder what it would’ve been like if my mother had lived. If she would’ve cared for me at all.’

Her words touched him.

He also wondered if his parents ever thought of him; if they’d found it easy to let him go. Even now, there was no contact between them. He’d never known if it was because they’d preferred it that way or because they’d been too ashamed to try. He preferred to believe the latter.

‘I guess it’s better not really knowing for certain,’ she added, with a wry smile. ‘This way I get to imagine what I want. And we must take our comfort where we can, don’t you think?’

He nodded.

He was reminded of the terror of leaving his parents, his village, even his brothers and sisters whose very existence guaranteed his expulsion from the family. And of the strange, dark figure of Madame Zed, who had taken his small hand firmly in her own and led him away to the station.

‘We have something in common,’ she informed him. They were sitting alone together in the cold, second-class compartment as the train pulled away.

He had tried not to speak; he was afraid of crying if he opened his mouth. But he managed to ask, ‘What’s that?’

‘We are both exiles,’ she said, fixing him with her steady black eyes.

And then, as the train wove through the countryside, she told him the story of how her family were arrested and executed one bright September afternoon at their estate outside St Petersburg, during the Red Terror. And how her old nurse, a devout woman with little care for her own life, had smuggled her out hidden in a hay wagon, wearing a kitchen maid’s clothing and clutching a knife hidden under her coat.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу