I glanced over at Spandi and saw his lips move with no sound. Suddenly, he turned to me and asked, “You know who your girlfriend’s boyfriend is, don’t you?”

“She’s not my girlfriend.” I laughed, pushing him hard in the stomach, the spell of the ceremony now broken.

“Whatever you say,” Spandi said, pushing me back. “Your friend’s boyfriend, then.”

“If you are referring to Haji Khalid Khan, then yes, I do know who he is.”

“Who?” Spandi challenged.

“He’s a businessman from Jalalabad. He imports diesel and ghee oil from Pakistan and Toyota car parts from Japan.”

“Of course he does.” Spandi laughed, slapping me on the back. “For God’s sake, Fawad! It’s Haji Khan! The Haji Khan—the scourge of the Taliban, the son of one of Afghanistan’s most famous mujahideen, and now one of the country’s biggest drug dealers. He’s Haji Khan, Fawad! I recognized him the moment I saw him. And he’s drinking tea at your house and sleeping with your girlfriend!”

5

5

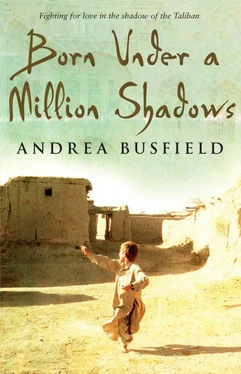

AFGHANISTAN IS FAMOUS for two things: fighting and growing poppies. And despite the best efforts of the international community to put a stop to both, we seem to be better than ever at these two occupations.

After the Taliban fled in 2001, the air was filled with talk about “democracy,” and within a couple of years everyone had the right to vote; women were allowed in Parliament; laws were written to protect the innocent; girls were allowed back in school; and all the wrongs done by our past leaders were apparently put right. But in the middle of all the excitement, everyone seemed to forget that Afghanistan already had a set of rules, a justice system going back thousands of years that was as much a part of our lives as the Hindu Kush mountains, and even though it was generally agreed that “democracy” was a good thing, the fact remained that if a man committed murder, then he was going to get it. Some blood feuds have gone on for generations in Afghanistan, with families carrying out so many killings nobody knows who started them anymore.

And even though the government has ordered everyone to give up their weapons for the greater good of the country, no one seems to be in a hurry to do so because things change so fast here. Therefore, the big men in the north and the west still fight over territory and power; army commanders in the east continue to shoot at Pakistanis who creep onto our soil uninvited; the Taliban fight goes on in the south against Afghans and foreigners; and in the streets the adults beat boys, the boys beat smaller boys, and everyone beats donkeys and dogs.

Meanwhile, the opium crops continue to grow, and grow, and grow, and the newspapers say that this year there was a record harvest, making Afghanistan the biggest opium producer in the world. Although my mother says everyone should work to be the best at something, I don’t think she has this in mind when she says it. I think she means math or religious studies.

And though I don’t know much, I do know that fighting is bad because people die, they lose body parts, and it makes the women cry; and I know it’s wrong to grow poppies because the West says it is and therefore so does President Karzai. So I don’t think I’m being childish or selfish when I say that Haji Khalid Khan, or Haji Khan as I now know him to be, is probably not the right man for an Englishwoman in Kabul who combs goats for a living, having, as he does, a history of violence and opium money in his pocket.

Although how I should convince Georgie of this is anyone’s guess. As my mother once said, and as Pir Hederi found to his cost, love is blind.

“Doesn’t Haji Khan come from Shinwar, not Jalalabad?” I asked Georgie as she drank her coffee on the steps of the house. It was cold now, and she was wrapped in a soft gray patu , a parting gift from her lover before he left for the east.

“Yes, he does,” she admitted. “But he has a house in Jalalabad and tends to spend most of his time there. Why do you ask?”

“Oh, nothing,” I mumbled, wrapping my arms around my body and coming to sit by her side.

“Here, get under this.” Georgie shuffled closer, placing the patu around my back and over my shoulder. It carried the heat of her body and the smell of her perfume. “Better?”

“Yes, thanks. It’s cold, isn’t it?”

“Yes, it is,” she agreed, and I bit at my bottom lip, not sure where to begin, and even less sure about whether Georgie would take the patu away once I did begin.

“What’s the matter?” she finally asked after we’d sat there in silence for the best part of a minute. “You look serious.”

“Do I? Well, yes, maybe I am,” I admitted. “It’s just that, well, I heard that there are a lot of poppy crops in Shinwar.”

“Not at the moment there aren’t; it’s winter.” She laughed.

“I know that,” I joined in, happy to have got the subject going at last. “But usually there are. Shinwar is famous for poppy.”

“Yes, I suppose it is,” Georgie agreed. “And your point is?”

“Nothing.” I shrugged. “I just thought I’d mention it.”

“Why? Because you think Khalid is involved in poppy?”

Georgie turned her head to look at me. To my gigantic relief she didn’t seem angry, but I still thought it best to ignore the question.

“Look,” she continued. “I know a lot of people think Khalid is involved in drugs because he’s a rich man, but he isn’t—isn’t involved in drugs, that is; of course he’s a rich man. Khalid hates drugs. He says they trap people in poverty, they damage the reputation of the country, and they pay for the insurgency that is threatening to wreck Afghanistan once again. He hates them, Fawad, absolutely hates them.”

“But how can you be sure he’s telling the truth?” I asked.

Georgie reached for the packet of cigarettes lying by her feet, removed one from the box, and lit it.

“Well, there are a number of reasons,” she explained, releasing a line of smoke through her lips. “I know he has several projects running in the east helping farmers find work away from poppy growing, like providing them with fruit and olive trees and seeds for wheat and perfume flowers. But mainly I know he’s telling the truth because I trust him.”

Georgie looked away, sipped her coffee, and sucked heavily on her cigarette. I turned my face to my feet and watched from the corner of my eye as she slowly dragged a pale hand through her hair, stroking it away from her face. Against the near-black of her hair and the gray of the patu , her skin looked frosty white, and dark circles hung beneath her eyes.

“Are you tired?” I asked.

“A little, yes,” she replied, a small smile thinning her lips.

I nodded. “I am too,” I said, which wasn’t true, but I didn’t want her to feel alone. Haji Khan had been gone a week, disappearing from our lives as suddenly as he had appeared, and I guessed she was missing him.

“I’ve known Khalid for three years,” Georgie stated, almost as if she had read my thoughts. “I would know if he was lying to me.”

“I didn’t say he was lying.”

“No. Well, not in so many words you didn’t, so, thank you.”

I shuffled my feet and let the softness of the patu cover them.

“But… how can you really be sure that he’s not?”

“How?” she asked, shrugging her shoulders in a very Afghan way that marked her out as nearly one of us. “Because I am.”

Читать дальше

5

5