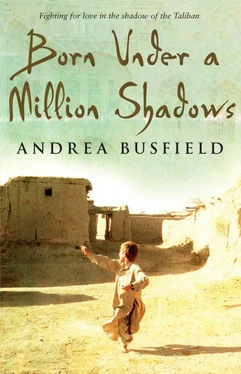

Andrea Busfield

BORN UNDER A MILLION SHADOWS

A Novel

For my mum, my dad, and my sister

Part One

1

1

MY NAME IS Fawad, and my mother tells me I was born under the shadow of the Taliban.

Because she said no more, I imagined her stepping out of the sunshine and into the dark, crouching in a corner to protect the stomach that was hiding me, while a man with a stick watched over us, ready to beat me into the world.

But then I grew up, and I realized I wasn’t the only one born under this shadow. There was my cousin Jahid, for one, and the girl Jamilla—we all worked the foreigners on Chicken Street together—and there was also my best friend, Spandi. Before I knew him, Spandi’s face was eaten by sand flies, giving him the one-year sore that left a mark as big as a fist on his cheek. He didn’t care, though, and neither did we, and while the rest of us were at school he sold spand to fat Westerners, which is why, even though his name was Abdullah, we called him Spandi.

Yes, all of us were born during the time of the Taliban, but I only heard my mother talk of them as men making shadows, so I guess if she’d ever learned to write she might have been a poet. Instead, and as Allah willed it, she swept the floors of the rich for a handful of afs that she hid in her clothes and guarded through the night.

“There are thieves everywhere,” she would hiss, an angry whisper that tied the points of her eyebrows together.

And, of course, she was right. I was one of them.

At the time, none of us thought of it as stealing. As Jahid explained, because he knew about such things, “It’s the moral distribution of wealth.”

“Sharing money,” added Jamilla. “We have nothing, they have everything, but they are too greedy to help poor people like us, as it is written in the Holy Koran, so we must help them be good. In a way, they are paying for our help. They just don’t know that they’re doing it.”

Of course, not all the foreigners paid for our “help” with closed eyes. Some of them actually gave us money—sometimes happily, sometimes out of shame, sometimes just to make us go away, which doesn’t really work because one group is quickly replaced by another when dollars are walking the street. But it was fun. Born under a shadow or not, me, Jahid, Jamilla, and Spandi spent our days in the sun, distributing the wealth of those who’d come to help us.

“It’s called reconstruction,” Jahid informed us one day as we sat on the curb waiting for a 4 × 4 to jump on. “The foreigners are here because they bombed our country to kill the Taliban, and now they have to build it again. The World Parliament made the order.”

“But why did they want to kill the Taliban?”

“Because they were friends with the Arabs and their king Osama bin Laden had a house in Kabul where he made hundreds of children with his forty wives. America hated bin Laden, and they knew he was fucking his wives so hard he would one day have an army of thousands, maybe millions, so they blew up a palace in their own country and blamed it on him. Then they came to Afghanistan to kill him, his wives, his children, and all of his friends. It’s called politics, Fawad.”

Jahid was probably the most educated boy I’d ever known. He always read the newspapers we found thrown away in the street, and he was older than the rest of us, although how much older nobody knows. We don’t celebrate birthdays in Afghanistan; we only remember victories and death. Jahid was also the best thief I’d ever known. Some days he would come away with handfuls of dollars, taken from the pocket of some foreigner as us smaller kids annoyed them to the point of tears. But if I was born under a shadow, Jahid was surely born under the full gaze of the devil himself because the truth was he was incredibly ugly. His teeth were stumpy smudges of brown, and one of his eyes danced to its own tune, rolling in its socket like a marble in a box. He also had a leg so lazy that he had to force it into line with the other.

“He’s a dirty little thief,” my mother would say. But she rarely had a kind word to say about anyone in her sister’s family. “You keep away from him… filling your head with such nonsense.”

How my mother actually thought I could keep away from Jahid was anyone’s guess. But this is a common problem with adults: they ask for the impossible and then make your life a misery when you can’t obey them. The fact is I lived under the same roof as Jahid, along with his fat cow of a mother, his donkey of a father, and two more of their dirty-faced children, Wahid and Obaidullah.

“All boys,” my uncle would declare proudly.

“And all ugly,” my mother would mutter under her chador, giving me a wink as she did so because it was us against them and although we had nothing at least our eyes looked in the same direction.

Together, all seven of us shared four small rooms and a hole in the yard. Not easy, then, to keep away from cousin Jahid as my mother demanded. It was an order President Karzai would have had problems fulfilling. However, my mother was never one for explaining, so she never told me how I should keep my distance. In fact, for a while my mother was never one for talking full stop.

On very rare occasions she would look up from her sewing to talk about the house we had once owned in Paghman. I was born there, but we fled before the pictures had time to plant themselves in my head. So I found my memories with the words of my mother, watching her eyes grow wide with pride as she described painted rooms lined with thick cushions of the deepest red; curtains covering glass windows; a kitchen so clean you could eat your food from the floor; and a garden full of yellow roses.

“We weren’t rich like those in Wazir Akbar Khan, Fawad, but we were happy,” she would tell me. “Of course that was long before the Taliban came. Now look at us! We don’t even own a tree from which we can hang ourselves.”

I was no expert, but it was pretty clear my mother was depressed.

She never talked about the family we had lost, only the building that had once hidden us—and not very effectively as it turned out. However, sometimes at night I would hear her whisper my sister’s name. She would then reach for me, pulling me closer to her body. And that’s how I knew she loved me.

On those occasions, lying almost as one on the cushions we sat on during the day, I’d be burning to talk. I’d feel the words crowding in my head, waiting to spill from my mouth. I wanted to know everything; about my father, about my brothers, about Mina. I was desperate to know them, to have them come alive in the words of my mother. But she only whispered my sister’s name, and like a coward I kept quiet because I was afraid that if I spoke I would break the spell and she would roll away from me.

By daylight, my mother would be gone from my side, already awake and pulling on her burka. As she left the house she would bark a list of orders that always started with “Go to school” and ended with “Keep away from Jahid.”

Читать дальше

1

1