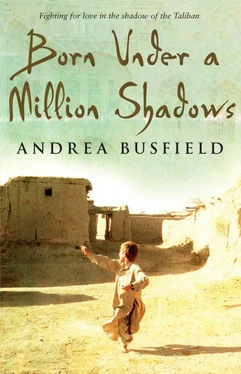

Meanwhile, as the foreigners argued a few extra dollars away, the women who also worked the street but knew no English would descend, hovering in shop doorways to reach out with their dirty hands, grab at elbows, and cry into their burkas. They all come from the same family, but the foreigners don’t know this, and as woman after woman would come to break down in tears pleading for money for her sick, dying baby, this would usually be the point when it became too much for the Westerners and they would climb back into their cars, trying to avoid our eyes as their drivers sped them away from our poverty and back to their privileged lives.

However, as the Land Cruisers screeched out of Chicken Street and into the gridlocked traffic of Shahr-e Naw, Spandi would appear to tap his black fingers on their windows and hold out the bitter, smoking can of herbs that we call spand , the smell of which is so unbelievably foul it is said to chase away evil spirits. Without doubt this is the worst of all our jobs because the smoke gets in your hair and your eyes and your chest and you end up looking like death. But the money is pretty okay because even if the tourists aren’t superstitious it’s hard to ignore a boy at a car window whose scarred face is the color of ash.

On a good day on Chicken Street we didn’t need to hustle. The foreign women would happily hand over their bags as they struggled with headscarves they had yet to grow used to, and I would carry their shopping until they called it a day, sometimes earning five dollars for my trouble. Jamilla would smile prettily and get the same for carrying nothing.

“And what is your name?” the women would ask slowly. Pretty white faces with smiling red lips.

“Fawad,” I would tell them.

“Your English is very good. Do you go to school?”

“Yes. School. Every day. I like very much.”

And it was true, we all went to school—even the girls if their fathers let them—but the days were short and the holidays long with months off in the winter and summer when it became too cold or too hot to study. However, the English we learned came only from the street. It was easy to pick up, and the foreigners liked to teach us.

And even if Jahid was correct and they did come to bomb our country and rebuild it again, I quite liked the foreigners with their sweaty white faces and fat pockets—which was just as well really, because that day I returned to my aunt’s house to be told we were going to live with three of them.

2

2

IT DIDN’T TAKE us long to move out of my aunt’s house, possessing as we did only one blanket, a few clothes, and a copy of the Koran. We would have taken more, but my aunt seemed to think that the few pots and pans we’d gathered over the years now belonged to her.

Thankfully, my mother was in no mood to argue that day and simply spit at her sister’s feet before lowering her burka and dragging me out of the door.

“Good-bye, Jahid!” I shouted behind me.

“Bye, Fawad jan!”

I looked back, surprised by the affectionate “jan” added to my name, and just in time to see my cousin wipe something from his one good eye.

“Don’t forget us, you donkey cunt!”

It was a quick extra that earned him an equally quick blow to the ear from the fat fist of his mother.

It took us two whole hours to walk from Khair Khana on the edge of the city to Wazir Akbar Khan, the location of our new house, in which time I managed to get from my mother that we were to live with two women and one man. She said she only knew the name of one of the women, the one who had invited us; her name was Georgie. And apparently, she had been washing Georgie ’s clothes for weeks.

I couldn’t believe she hadn’t mentioned this before.

“But why were you washing her clothes?” I asked.

“For money, what do you think?”

“Why doesn’t she wash her own clothes?”

“Foreigners don’t know how. They need machines to wash their clothes.”

“What kind of machines?”

“Washing machines.”

This sounded incredible to me, but my mother wouldn’t lie. Okay, she didn’t talk much, but when she did it was always the truth. I also knew that foreigners were a Godless people, so I had to assume that as well as going to Hell they hadn’t even been blessed with the common skills given to ordinary Afghans like us.

“Does she sew?”

“No.”

“Can she cook?”

“No.”

“Does she have a husband?”

“No.”

“I’m not surprised.”

Mother laughed and dragged me into a hug as we walked. I looked up, but I couldn’t see her face through the screen of the burka, so I held her hand tighter, my ears burning at the thought of having made her smile.

This was fast turning into the best day of my life.

Although I had no real memories of what it had been like before my aunt’s house, I knew my mother was miserable after we moved from Paghman. Locked in one room with a thin carpet that offered no comfort from the cold scratches of the concrete floor, we lived, ate, and slept like tolerated prisoners under my aunt’s roof. The toilet was also a constant torment to my mother, smattered as it usually was by the missed aims of four careless boys and a man whose bowels were as loose as a slaughtered goat’s; and we were plagued with illness, from malaria in the summer to flu in the winter, as well as the worms and bugs that permanently lived in our stomachs. Yet we had to appear grateful because my aunt had taken us in on the night we lost everything.

Every year, people around us died from disease, rocket attacks, forgotten mines, the bites of animals large and small, and even hunger. And even if you did have food, that was no guarantee of coming out of the day alive. Mother cooked our meals on an old gas burner that sat in the corner of our room threatening to explode and knock the heads from our very necks. That’s what happened to Haji Mohammad’s wife three doors away. She was cooking chickpeas in the kitchen when the burner exploded into a ball of flames. It then shot from the floor like a rocket, taking her head clean off. It took him weeks to clear the blood and brains from the black remains of the kitchen. Even today, dents from bullet-propelled chickpeas scar the walls of the house, and Haji Mohammad won’t eat anything but salad, fruit, and naan. Anything, in fact, that doesn’t need cooking. Thanks be to Allah, though, because he’d been blessed with a second wife—and she was younger than the first.

“So, how did you get to know her?”

“Who?”

“The foreign woman, Georgie.”

“I found her.”

“What do you mean you found her? How did you find her?”

“Oh, Fawad! So many questions! I was knocking on doors looking for work, and she gave me some. After that she gave me some more, and then she invited us to come. Okay?”

“Okay.”

As we marched through the streets, dodging dog shit and potholes, and with my mother now refusing to give any more information as to how we came to be moving toward this sudden freedom, I tried to imagine the mysterious Georgie who had been found by my mother. I pictured a woman with long golden hair and an easy smile standing under a tree in Wazir Akbar Khan, looking lost with her arms full of the dirty clothes she had no idea how to wash. In my head she looked like the woman from Titanic . In reality, she looked more Afghan than I did.

Turning left, just before Massoud Circle, we crisscrossed three roads lined with concrete barriers protecting huge houses that peered over high walls with curls of barbed wire fixed on them. Men holding guns stood guard every ten paces, and they eyed us with lazy suspicion as we moved farther into the residential area of the rich. Eventually we came to a standstill in front of a large green metal gate. Another guard wearing a light blue shirt and black trousers came out of a wooden white hut positioned nearby and greeted my mother. He then opened the side door and shouted inside. As we stepped through, a woman came walking toward us with hair as long and dark as my mother’s. She wore a white shirt over blue jeans and looked quite beautiful.

Читать дальше

2

2