4

4

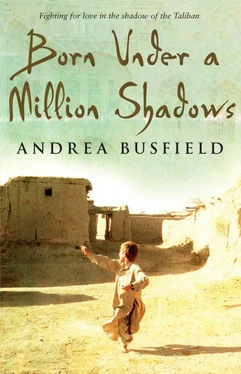

AUTUMN IS MY favorite season in Kabul. After the burning heat of summer, the air relaxes, allowing a cool wind to travel through the city, carrying the smell of wood fires and smoking kebabs on its back. The night comes early, swallowing up the day before it’s barely begun, and a million gas burners and single lightbulbs shine from stores built out of old shipping containers that snake through the city, making it glow like a massive wedding party.

I know most people think of spring as the season of new beginnings, when women chase the winter dirt from their homes, when the plants come out of hiding and the animals give birth to their babies, but for me autumn is the season that whispers fresh promise.

Coming as it did during the holy time of Ramazan, when the adults step closer to Allah through fasting and prayers, it was autumn when the Taliban finally gave up control of Afghanistan. One November night they simply fled from the capital in pickups and stolen cars as the soldiers of the Northern Alliance rumbled in from the Shomali Plain to take Kabul without a fight. At the gate of the city where the hill dips to an easy slope, I watched from Spandi’s house as thousands of men dressed in uniforms and salwar kameez gathered in groups, leaning lazily on the tanks and jeeps that had brought them there, their guns slung casually over their shoulders. It was like a huge picnic rather than a war as local men came out of their homes to offer what food and water they had to the new conquerors of Afghanistan.

As me, Spandi, and Jahid sat watching at the window—a five-minute walk from where the soldiers were eating, smoking, and laughing—we all confessed to being mightily disappointed at the lack of fighting. For weeks the Taliban had been spitting insults and threats across the radio, vowing to fight the Northern Alliance and their infidel backers to the very last man. But when the time came to stand, the Taliban ran away like frightened dogs, leaving only the Arabs and Pakistanis to carry out their suicidal ideas of war.

“We should go down and welcome them,” Jahid suggested as we watched the swarm of figures silhouetted by the headlights of their vehicles.

“Good idea,” I said. “Let’s do it.”

“Not so fast, gentlemen,” Spandi ordered, his face a lighter shade of gray than it is today. “You can’t know a man’s real intentions in only one night.”

I looked at Spandi with something close to wonder. It was the wisest thing I’d ever heard anyone say.

Smiling shyly, he added, “My father told me that.”

“Your father should be working for the Genius Ministry!” I laughed, because Spandi’s father was one hundred percent right.

My mother told me that when the Taliban originally came marching from the south to lay claim to Kabul, they were welcomed like saviors. The capital had become a city of rubble after the Russians left because the victorious mujahideen had turned on one another, fighting like dogs over a piece of meat—and Kabul was that piece of meat. In the chaos and confusion of civil war, crime was everywhere; shops were made to pay special taxes, homes were taken, people were murdered, and their daughters were raped. But when the Taliban came, it all stopped. Order was brought, and the people were grateful. However, as Spandi’s father said, you cannot know a man’s real intentions in only one night, and over the years the Taliban showed their true colors. They stopped women from working, they wouldn’t let girls go to school, they roamed the streets beating people with sticks, they jailed men with short beards, they banned kite flying and music, they chopped off hands, they crushed people under walls, and they shot people in the football stadium. They had freed Afghanistan from war, but they locked up our people in a religion we no longer recognized. And it was only the warm winds of autumn that finally blew them away.

“The Taliban were bastards all right,” declared Pir Hederi as I sorted through the crates of fruit and moldering vegetables to see what could be saved for the morning. “Thick as cow shit as well. Most of them were small men from small villages who’d never been taught to read and write. Hell, even their leaders were illiterate.”

“Can you read and write?” I asked, scraping the mold off one potato and putting it in the “for sale” box.

“No, Fawad, I’m blind.”

“Oh yeah, sorry about that.”

“Blame the wife.”

“So how did they get to rule Afghanistan then,” I asked, “if they were so stupid?”

“Through fear,” mumbled Pir as he picked the dry dust from the inside of his nose. “Your mother was right: when they first arrived everybody more or less loved them. The country was being bombed to hell by warlords who worked only to fill their own pockets, and the people were scared and tired of being scared. Suddenly this group of fighters emerged from Kandahar promising order, preaching Islam, and hanging child rapists. Who wouldn’t welcome them?”

“Welcome who?” Spandi asked, arriving out of the dark, his can hanging smokeless and hooked on the waistband of his jeans.

“The Taliban,” I answered.

“Oh, those bastards.”

Pir started cackling. “Exactly, son. Come, take the weight off your feet.”

Spandi pulled up a crate and kicked off his shoes. He had become a regular visitor to the shop after finding me throwing rubbish into a ditch at the end of the street a few weeks back. He had been walking to Old Makroyan at the time, the sprawl of flats he and his father had moved to after the fall of the Taliban. In their golden days the blocks of Old Makroyan were the pride of the city, but now they were no more than slum dwellings, a new hole for Kabul’s lost to fall into. But they were closer to the city than Khair Khana, which made it easier to find work.

“So, where was I?” Pir asked, magically picking out a can of Pepsi, which he handed to Spandi.

“The people were welcoming the Taliban because they killed child rapists and talked about Islam,” I reminded him.

“Oh yes, Islam.” He sighed, nodding his head thoughtfully. “Of course, it was a very strict interpretation of sharia law that they preached, and it brought back public executions and floggings. Kites were also banned, as were televisions and music. You couldn’t even clap your hands at sporting events anymore—not that I’ve ever been able to see who was winning anyway. At one point they even put a stop to New Year celebrations. In fact the only thing we were permitted to do was walk to the park and sniff at the flowers. Damn homosexuals. But really it was the women who had it worse than anyone else.”

“I know,” Spandi interrupted. “My father knew a woman who had all of her fingers cut off by the religious police just because she’d colored her nails.”

“See!” Pir shouted. “That’s exactly what they were like!”

“But why did they do it?” I asked, unable to understand why anyone should cut off the fingers of someone’s mother just for the sake of some paint.

“They said it was to protect women’s honor. In reality it was because they were out-and-out bastards. Why do you think anyone who was anyone tried to escape to Pakistan?”

“The Pakistanis are all bastards too,” mumbled Spandi.

“Right again, son,” Pir agreed. “But at least they offered people some standard of living. Despite the promises, this place went to shit under the Taliban. There was hardly enough food, minimal clean water, and even fewer jobs. The government was a shambles, and the whole damn machine began to grind to a halt. Then, what do you know? When food prices soared and conditions sank so low we could no longer see the sun, or feel it in my case, the Taliban’s planning minister, a man called Qari Din Mohammad, told the world we didn’t need international help because ‘we Muslims believe God the Almighty will feed everybody one way or another.’ Bullshit! God had enough on His plate trying to keep us alive.”

Читать дальше

4

4