And there is always this respite in the morning, misplaced and temporary, but a breathing space at least. Alex sat back in the taxi’s soft seat, conveyed without effort towards his destination.

The cloud cover had thickened while he was underground; the streets had gone shadowed and dim, as if the sun had barely risen, and the sky was a low churn of black and dark slate grey, the under-sides of the cloud drifts edged with brilliance. The taxi pulled into the parking lot of the hospital.

People were crossing the tiles of the lobby, the lights fully on now, a wide fluorescent space. Near the information desk, a woman with thick hair like yarn was sitting on a bench, turning her hands in her lap. She stared at Alex as he passed.

‘There’s going to be a wind,’ she said loudly. ‘There’s going to be a great wind tomorrow.’

‘Yes,’ said Alex. ‘You’re probably right.’

She turned away from him then, and he walked on into the hallway.

He went to the pharmacy on the ground floor, handed over his prescription slip and got back a plastic bottle of antibiotics, then took the elevator up to his office.

The Rifampin was chalky and foul-tasting, and Alex drank some fruit juice and ate a stale muffin that had been sitting in his desk drawer, then called Fiona to find out if he was working or not. No, she said, he had taken two sick days for the laser surgery, and what was he doing in his office at all?

‘I’ve been having trouble keeping track,’ he said.

Susie wasn’t in the ICU waiting room, but her gloves were sitting on the table, beside an unopened bottle of Rifampin. He waited in the doorway until he saw her coming, walking slowly down the corridor from the ward, each footstep deliberate as if she were balanced on a string. She was still wearing her coat, though the rooms were warm; her hair matted on one side, her face blotchy and raw. She pushed through the double glass doors, but she didn’t notice him right away – she went to the vending machine outside the waiting room and pushed the buttons with delicate disoriented precision, knelt down to remove a chocolate bar.

‘Hi,’ said Alex.

‘Yeah. Okay.’ She walked into the waiting room and sat down.

There were any number of ways this could have ended that might have seemed simple and sad and final, satisfying in an elegiac way. But our lives are great shambling stupid things, the flawed nerve paths of memory and randomly built excuses for the body, and we are mostly still trying to make them come out right when we die. He followed her into the room.

‘How are you?’

‘I don’t know,’ she said. ‘I need to find his psychiatrist, I think. They aren’t sure about meds and stuff.’

‘Can I help?’

‘I can’t see how.’ She crumpled the candy’s foil wrapping. ‘I told you to go home.’

‘Yes. I decided not to.’

She shrugged. ‘Not my problem.’

‘All right.’

‘I fell asleep for a bit,’ she said. ‘I had this dream where I had a sort of a baby, this little wet white rag doll thing, but it just sort of fell out of me and I forgot about it, and it fell in a corner with its face against the wall and it couldn’t breathe and it died before I found it. It was like, how do you do CPR on a rag doll? I hate it when my dreams are so fucking obvious.’ She broke off a corner of the chocolate and put it in her mouth.

‘How is Derek?’

‘I don’t know. How is he ever?’ She set down the chocolate bar and wrapped her arms around herself. ‘I never meant to lose him,’ she said softly. ‘I tried, you know, I really did.’

‘You saved his life.’

‘No. Not in the way that counts. I let him go. I let him go away.’

‘Susie, there was nothing you could have done.’

‘But there should have been, don’t you see? There should have been.’

He heard a soft shimmer sound at the window, and looked up to see that it had started to rain, a filmy veil spread over the glass.

‘You haven’t taken your antibiotic,’ he said.

‘I will. In a bit.’

‘Well, when?’

‘I don’t know. Soon. When I feel like it.’

Alex watched her as she pulled her fingers through a tangled bit of hair, and he remembered something else about that day at the clinic, Susie hanging in the air and refusing to speak, knowing the policeman had his nightstick out, knowing he would hit her. The strength of her refusal. Derek’s tremendous negative power, under his bridge renouncing the world, the extreme and appalling force of doing nothing.

‘Take it now.’

‘Drop it, okay? I told you I’ll do it soon.’

‘No,’ said Alex. ‘Not soon. Now. I want to see you take it.’

‘Is there something wrong with you?’

‘I swear to God, Suzanne, if I have to pour it down your throat myself, I will do it.’ He felt like a fool, he was probably making himself ridiculous. Susie stared at him for a long time, and he looked back at her, and he didn’t know which one of them would break first.

‘You don’t own me,’ she said at last.

What he was going to say next terrified him, but he said it anyway.

‘Yes, I do,’ he said.

She stood up abruptly, the plastic bottle in her hands. ‘Jesus, Alex. You’ve got some fucking nerve.’

‘It’s probably not even a good thing, but there it is.’

He knew that he was saying something outrageous, that you were never, ever allowed to say this, but suddenly he couldn’t understand why, when no one could go on for a single day without this, all the passionate and harmful and endless ways that people owned each other. He had no right to this, none at all, it was just there, like Canadian weather; because sometime long ago she had been falling, and he had been the one nearby.

The edges of her hair were dark with sweat, but her skin was pale, and she had that look on her face again, like someone very young who wanted something badly, and believed that asking for it would doom her.

‘You make it so bloody hard,’ she said.

‘I’m sorry,’ he said. ‘I’m sorry. You scare me to death.’

He stood up and put his arms around her, and she leaned into his chest and hung on to his shirt with her hands, the medicine bottle pressed between them. He was a contingent person, his time artificially purchased, but this was his life, the rest of his life was contained in this, and it didn’t make him happy exactly any more than breath or insulin made him happy; it was simply necessary.

‘Take the antibiotic, okay?’ he murmured.

Susie pulled slowly away from him and sat down at the table. ‘I was always going to,’ she said, breaking the security seal on the bottle and pouring the thick suspension into the cup. ‘Honest to God, I was. You just make up stories about me. You’ve got to stop that.’

‘That’s a problem,’ said Alex. ‘I’m not sure I can.’

Susie sighed, swallowed the dose and grimaced. ‘Yeah. You and my brother. And the rest of the world, it seems like.’

‘It’s what people do, I think. But I really am sorry.’ He reached out and combed a strand of her hair between his fingers, and she sighed, inclining her head in his direction.

There would be a time, some years later, when he would be sitting in a dim room drinking coffee and talking to Evelyn, of all people, trying to explain what this moment meant, and the only thing he would be able to say was that it was not by then a choice but more like a gravitational process, and all you could do about gravity was to love its force.

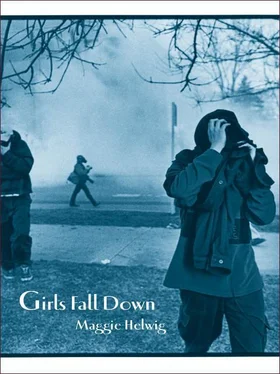

On the surface of the city, above the tunnels and sunken gardens, the temperature has risen just enough for a cold rain to begin falling. Inside a little brick church, the rain is a muffled sound through an opened door, as a woman in a violet robe raises her arms in consecration, the elements transformed. She turns to place a wafer in her daughter’s hands. In the basement, someone is painting NO WAR on an old bedsheet, aware that the war will happen regardless. Out on the street, a man covers his mouth, and watches for signs of poison gas.

Читать дальше