In the message, Lily sobbed weakly. She lamented the fate of the dead animal in Sebastien’s picture; she warbled about a mistake she had made. It was not a confession, of course—it meant nothing, less than nothing. The mistakes Lily had made in her life were so heartbreakingly minor that Andrew was not sure she would even remember them when she grew up. And yet the time of the call was within the span during which the pathologists posited that Katy had died, and Anna—curiously—had seen fit to withhold the message. It was not certain that the fact of the withholding, per se, would be allowed in court. But it was certain that Anna would now have to testify—about what she’d felt when she first heard the message, and about what she’d later feared it might have meant.

There was something else wrong with the message, though it took Andrew a while to figure it out. He’d heard the story of the night Katy died so many times that it was like an incantation, like a children’s song predating language or memory. Hearing the story on the voicemail was disorienting, like walking into a room with the furniture moved; every time he listened to the message, the version he’d heard before momentarily superimposed itself over this new one. Until, after a few listens, he’d caught it.

I went to the river , Lily had said. Most people’s voices seemed higher when recorded, but hers had sounded lower. I went to the river . In the stories Lily had told of that night, she had not mentioned a river. And I went to the river, she’d said. I, not we. What had happened at the river? Nothing had happened at the river. What did it mean that she’d gone to the river? It meant nothing that she’d gone to the river. And yet in the previous tellings of the story, there had never been a river.

Out the taxi window, the moon was a glowing auricle in the sky. The light it cast made Maureen’s face look angular and not quite realistic, as though she’d stepped out of a painting from one of those movements that sought to portray people not as they appeared but as they actually were.

Andrew rolled down the window and let the air rush in at him. He thought of his Lily, alone at night, leaving Sebastien LeCompte’s house and going outside—for her own reasons, innocent and unknowable, both. It was terrifying to think of Lily doing anything alone at night. It was more terrifying—much more—to think of her never doing anything alone ever again.

Andrew thought of the phantom river with his phantom daughter beside it. It would have looked icy, probably, in the moonlight. Lily had merely done what Andrew had dreamed of doing so many times when Janie was sick, so many times since then: Without telling anyone, without asking anyone, she had opened a door and walked away.

“Andrew,” said Maureen. He could feel her looking at him in the darkness, and he turned his face to meet her gaze.

“Yes.” Out of the vast thicket of preexisting worries and sorrows that Andrew knew intimately, a new unnameable fear was seizing him. It released him and then seized him again, a clonic coursing, gripping and then relenting.

“You watched that security footage of her at the store?” said Maureen. “With Sebastien?”

“A few times, yeah.”

“Me, too.” The taxi rounded the corner to their hotel. Maureen turned back to the window. And she was still looking away from Andrew when she said, “Did you ever know that she smoked?”

July

Sebastien went to court every day for three weeks before Lily finally took the stand.

It was obvious as she testified that she’d been told to speak clearly and slowly; it was obvious that she’d been told to make eye contact. It was a mercy that nobody had told her to smile—that this was a performance that did not require cheer—because the smile she gave in pictures, Sebastien thought, really could make someone wonder about her. Her Spanish was much better now. Her hair was growing in, but its shortness made her face more severe, more frank, than it usually was. She wore an array of mock turtlenecks, often in pale pink—which struck Sebastien as so bizarre, so clearly not a choice she’d made; they reminded him of a picture he’d once seen of a skinny African child wearing a donated vanity T-shirt designed for some family’s 1993 reunion barbecue. The incongruousness of Lily’s shirt had to have been part of the strategy, Sebastien figured. It must have been chosen not only for its modesty, its subdued femininity, but also for the way it showed the world that Lily was a captive now—that she was a prisoner, that she would take whatever shirt you gave her and wear it gratefully, that she was sorry, that she had not killed Katy Kellers but she was still sorry for everything else, she was sorry for the way she was and what she had and who she’d been, and that she had learned her lesson, and that the world could afford to forgive her.

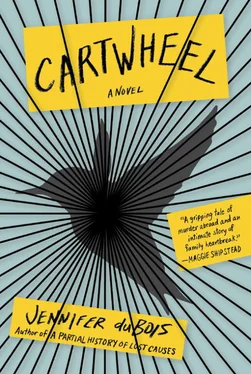

Sitting in the courtroom, Sebastien listened to Lily explain the cartwheel—slowly and carefully, while making forced eye contact with a different arbitrary stranger every few seconds. She had done the cartwheel, she said, not to mock or disdain Katy’s death, and not to try to seem defiant or brave. She had done it, she said, simply because she’d felt helpless. She’d wanted to show herself that she could still do this one small thing. Maybe she couldn’t do anything else, but she could still do this.

And then, sitting in the courtroom, Sebastien listened—again—to the voicemail. The sound of Lily’s recorded crying filled the room. Sebastien still wanted to believe that that voice was crying over him. But he knew better now than to let himself believe something he so badly wanted to.

In the end, it was a relatively quick trial.

By the time Eduardo and Adelmo Benitez, the instructor judge, brought the case before the court, the story was neat and compelling. The DNA evidence had Lily handling the murder weapon; the delivery truck driver had her present and bloodied at the scene of the crime; her ruined alibi left Ignacio Toledo’s confession essentially unchallenged and unchallengeable. All that was left to do was stand back and watch motives orbit Lily like planets around a star.

First, Katy weighed in from the beyond, with her cryptic message about the new romance in her life, the one she was afraid would upset Lily terribly. Next was Beatriz Carrizo, shaking more from holy anger than from nervousness, describing how Lily had spied and snooped and snuck out and been fired from her job, how not one week had gone by—literally not one week—when she hadn’t been in some kind of trouble or another. But really, the bulk of the work was done by Lily herself—bit by bit and word by word, in the emails, the voicemail, the fight, the lies—making Eduardo’s case more convincingly than even he could have done, long before she ever took the stand.

Next came Lily herself, speaking first for the defense. By now her Spanish was excellent, newly and finally fluid. She’d learned idioms and slang. She had, you could be sure, learned swears. Her Spanish now was the kind of thing you could dream in and rely on, and Eduardo was sure that she was sure that if she could have had the chance to do everything over—if she could have dubbed the last few months into this Spanish—that none of it would have happened. But, of course, it would have, and anyone could have seen it; her perverse callousness toward Katy required no articulation, and thus no translation. If anything, Lily came across worse in this improved Spanish than she had before. The newly jovial emphasis in her speech—her unself-conscious willingness to really commit to the accent—clashed strangely with her dispassionate account of Katy Kellers’s life and death. When her Spanish had been broken, limited, there was a sense that perhaps the nuance of her experience and perception was being lost; that perhaps a fuller, more sympathetic picture existed just on the other side of fluency. But now when Lily spoke you could be sure she knew what she was saying; and so when she issued some gigglingly inappropriate non sequitur about the quality of Katy Kellers’s orthodontia, one of the judges frowned and removed his bifocals and made a note of it, sure that whatever he was hearing was exactly what was meant.

Читать дальше