He had been very, very stoned.

“Yes,” said Sebastien.

“You were together all evening?”

But who was to say Lily hadn’t been beside him the whole time? It had seemed as though she’d been gone a long while, but perhaps she had not been. It had seemed as though she was leaving the house, but maybe she never had. And once Sebastien had told the first lie, it was easy to tell the second.

“Yes,” he said again.

When the first officer left, the second officer appeared and conducted the same interview over again; somehow Sebastien understood—though he didn’t know why—that this switching off meant that all of these conversations were merely the preliminaries. The second officer had the kind of face one wanted very much to lie to, but Sebastien resisted the impulse to introduce any new deceits. Instead, he stuck to his first set of answers, and this time he felt—and, he was sure, sounded—much more certain of them than before.

Afterward, the police drove Sebastien home. It was dark outside, which meant it had to be very late. They dropped him at his house, and he went inside to wait for Lily to come meet him. A week later, he was still waiting.

Slowly, it became clear to Sebastien that they were not going to let him see Lily—though he went every day (rather gallantly, he thought) and asked. Only family was allowed to see her, they said, and only on Thursdays. They did let him leave her things: notes, phone cards, and, in a fit of inspiration and bribery, a journal and pen. But they never let him in, and Lily’s father—who had appeared at Sebastien’s door one day, bristling with the politest rage Sebastien had ever seen, and clearly half-expecting to find Sebastien in the midst of committing a homicide in the foyer—said that they were unlikely even to allow Sebastien to call her.

Sebastien had expected to encounter some opposition in going to the jail—enough, at least, so that he might feel that he was suffering along with Lily on some small level. Beyond submitting his DNA sample—a terrible indignity made endurable only by the thought that he was doing it for her—nothing much had been asked of Sebastien; he wished he could throw himself into the awful place where Lily was, beat his fist against its walls, demand that it hurt him, too. But everyone at the jail was maddeningly polite, even apologetic, when they told Sebastien, for the fifth or seventh or tenth time, that no, he could not see her. When he argued, they shrugged the divested shrugs of people who are enacting a script they did not write and did not necessarily even think was very good. One of the security officers—a woman, blinking down at Sebastien from behind bulletproof glass—even seemed to find his situation somewhat sweetly amusing, and eventually Sebastien began to understand that she would actually have liked to let him see Lily, if she could have. But she couldn’t. When Sebastien realized that he wasn’t up against anything he could actually see, he grew exhausted. He stopped going to the jail for a few days. And then—finally, lamentably—he bought a television.

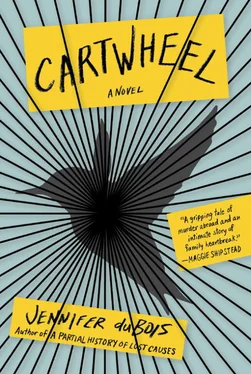

The television, in general, proved to be a bad idea. When the Telecom man arrived to install it—surprised not to be replacing or supplementing another set—Sebastien explained that he was looking to get information about a particular story in the news. He could not have fathomed then how much information he would get. The daytime news channels, in particular, seemed to cater exclusively to people exactly like Sebastien—people without work or diversions, people who had nothing to do but sit around, underdressed and agape, and obsess over every single detail of the case of the murdered Katy Kellers and the accused Lily Hayes. The reporting was speculative and circular and redundant and endless, and Sebastien found himself disappearing into it for many strange, amnesiac hours. After a day with the television, Sebastien had seen the news cycles begin and end and begin anew; he had witnessed each anchor repeat him- or herself nearly verbatim several times over. The anchors’ surprise never diminished with repetition—the fact that Lily had apparently done a cartwheel during her interrogation, for example, was marveled at with an astonishment that seemed to grow only more vigorous over the hours. By the end of the first day, Sebastien suspected all of the anchors of traumatic brain injury. By the end of the second day, he suspected them all of genius. He tried to track the variance in tone and emphasis, the subtle shifts in syntax, the inversions of word order, as they recounted the same news item again and again; it occurred to Sebastien that they might be speaking in a code too sophisticated and nuanced for the crude instruments of quotidian comprehension. After all, wasn’t there something fundamentally different about the meaning of Lily Hayes was widely known for her erratic behavior and Lily Hayes’s erratic behavior was widely known ? After two days with the television, Sebastien began to feel that there was.

From what Sebastien could gather, the television’s suspicion of Lily seemed to hinge partly on the order in which she had done certain things on the day after the murder. The most damning fact, it seemed, was that a delivery truck driver had seen Lily running across the lawn with blood on her face before she called the police at Sebastien’s. On TV, this point wound up yielding two different insinuating questions, asked over and over by a rotating handful of commentators—though always in the same tone of energetic inquiry that invited viewers to believe that these important queries had only just occurred to them (the commentators), and that they (the viewers) were watching substantive thinking in real time on live television and that this was why it was worth paying for cable.

The questions were these: 1. Why, the pundits asked, had Lily not called the police first before running to Sebastien’s? (Unless, of course, she was running away in guilt, trying desperately to leave the scene before the law arrived.) 2. And why , pondered the pundits, had she stayed at Sebastien’s that night—mere steps from where Katy was slain—since she could not know that the killer would not return to the neighborhood? (Unless, of course, she knew precisely who the killer or killers were, and exactly how afraid of them she really needed to be.) The suppressed premises of these questions seemed contradictory to Sebastien but, apparently, to no one else; they were always paraded out together and were often mentioned in nearly the same breath, as though the one compounded the other instead of substantially subverting it.

Though the bulk of the information was repetitive, every day the TV unearthed some new bit of trivia: Here was Lily’s report card (she’d only been making Bs in Spanish!); and here was a picture of Lily as a child in a school play (dressed as a green pepper and clearly overacting); and here was an unkind Facebook message exchange Lily had had with a friend about a third girl (whose name was redacted but who was, in Lily’s estimation, “just unfuckingbelievable”). Sebastien would catch himself feeling fascinated by and a little grateful for the information the TV dug up for segments about Lily’s online persona—at the end of the day, is this the social network profile of a killer?—before remembering to feel horrified and then ashamed. He’d vow to guard against this curiosity, though he did not turn off the TV. Somewhere along the line he had convinced himself that if information was power, then rapt information gathering was loyalty.

In odd moments Sebastien would startle to see an image of himself on the screen—though he shut his eyes whenever they showed that episode near the Changomas condom shelf or the shot of him and Lily kissing, mouths visibly open, the police tape flapping behind them. (One of the lesser tragedies from this great tragedy, Sebastien figured, was that he would never be able to kiss anybody ever again.) He began to imagine what his whole life might look like as told through security camera videotape: Here he is jubilantly pouring coffee at a Cambridge 7-Eleven during that Harvard admitted students’ visiting weekend; here he is hunting for a suit to wear to his parents’ funeral, his face oyster-gray and formless; here he is shopping for cereal at his corner bodega, again and again and again, alone. All of these images existed somewhere out in the universe, Sebastien now realized, and they would show a version of his biography if somebody ever decided to collect and arrange them. And Sebastien saw how convincing the security tape telling of his life would be—to the average viewer, or even to him—no matter how many other true things were missing.

Читать дальше