There were a lot of transcripts—the police’s first talks with the neighbors, the vendors, the traumatized American study-abroad students, the family who’d been hosting both girls, the improbably named boy who had been kissing Lily Hayes in the garden. But the conversation with Lily Hayes stood out, and not only because there was no sign of a break-in and she was the only person in a hundred kilometers who’d had a house key. Eduardo read the transcript in his apartment with the shades drawn, while the sky outside his window stayed maddeningly light well past eight o’clock. In the transcript, of course, it was difficult to ascertain exactly what Lily Hayes’s tone had been as she answered questions about Katy Kellers’s short life and violent death. But Eduardo detected a cold current, a psychological dislocation, that made him read and reread the interview—though, for obvious reasons, Lily Hayes was not likely to have been the sole perpetrator of the crime.

“You say you saw some blood in the bathroom,” said the interviewing officer.

“Yes,” said Lily.

“How much blood was there, exactly?”

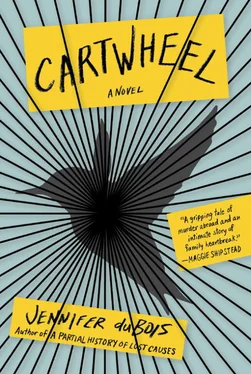

“Not much,” she said—and Eduardo could feel the pause there, the implied flippancy. At one point, the transcript remarked flatly that Lily Hayes, left briefly alone but for the watchful gaze of the security camera, had done a cartwheel. Eduardo turned this image over in his mind. He regarded it without judgment. He was surer, but he was not yet sure. And it was very important to be sure, because once he was sure, he was never wrong.

The next morning, Eduardo arose before dawn to run through the darkness. He was sweating by the end of the block; he was, as usual, overdressed for the weather. He could never believe that the world outside was so much warmer than it looked.

The running was new, though the general ritualized masochism was not. Whenever Eduardo felt it coming back again, he commenced a series of steps, a sequence arrived at through guessing and testing and the emergence of a grim, white-knuckled will. First, he assessed all the things in life that would make him feel worse. You won’t feel any better if you get fat, he’d tell himself, while jogging. You won’t feel any better if you get gingivitis, he’d tell himself, while flossing. The corollary—which was intrusive and unarticulated and omnipresent—was that he wouldn’t feel any better either way. It never worked, of course. But it did make Eduardo feel as though he had tried. If Eduardo did anything, it was try. And, after all, it had been only two months since Maria left.

Maria—Eduardo would be the first to admit—had crashed into his existence, unearned, unwarranted. They’d been married for three years, and during that time Eduardo had never entirely gotten used to the idea. So when she left him—for a Brazilian opera singer, he’d heard—who was Eduardo to say she was not making the right decision? He had felt, somewhere in his devastation, that the universe was actually righting itself, and that resenting this was irrational. And if Eduardo was anything, it was rational.

Around him, Belgrano’s streets were rain-slicked and silver. Eduardo tried to breathe evenly. He thought about all the cigarettes he hadn’t smoked in the fifteen years since he’d quit. Could he feel the difference in his breathing? He was not sure. Sun split the clouds, startling a flock of birds off their telephone line. Eduardo could not feel a difference, he decided. But he did feel a little stab of virtue every time he wanted and did not allow himself a cigarette, which was still a few times a day, every day, even now. Sometimes it seemed to Eduardo that his whole life was only a collection of small impulses denied. The birds flew over his head, casting chevrons of shadow on the concrete.

At least, Eduardo knew, his work would not suffer. In the very precise triage system he’d set up within his life, work was the most critical priority. And on his better depressed days, Eduardo didn’t so much as snap out of his sadness as sink into it—it contracted in his chest like a heart, giving him some propulsive force as he moved through an investigation. This compulsion to work could sometimes feel congenital, genetic—though, in fact, Eduardo had not originally wanted to be a lawyer. He had studied piano as a teenager and had hoped to continue in college, right up until the day he watched Julio César Strassera deliver closing remarks in the Trial of the Juntas. It was 1985 and Eduardo was sixteen. He’d been practicing Mozart’s Sonata in F Major for a school recital that would later be canceled due to bomb threats, and his time with the school’s piano was limited, but still he went to the cervecería across the street to watch. Never again, said Strassera. The television cut to footage of the Mothers, testifying. The bar around Eduardo smelled sour, and a man next to him was crying. One of the Mothers looked straight into the camera. “What has happened cannot be fixed,” she said. “It can only be told.” On her face was an expression of righteous sadness, a grief well beyond weeping. And suddenly Eduardo understood—with shocking and fatal clarity—that she was not trying to get her child back. This thought had never really occurred to him before. “They have to be dead,” the woman was saying, “but they are only truly desaparecido if we turn away. They are only really gone once we stop looking for them.”

Standing before the television, Mozart’s allegro still throbbing in his fingertips, Eduardo had felt himself rising to a grave and difficult understanding. Perhaps this was only because he’d been looking for one—he was, after all, sixteen. But whatever the reason, he’d known that he was seeing something he could not forget: He was learning that goodness could not be goodness if it was dimensionless and passive; he was beginning to believe that there was a compassion beyond compassion. Eduardo looked at the Mother’s face, and he saw that forgiveness without justice was not Christ’s forgiveness, or any other kind worth extending. He walked out into the blazing sun and did not return to the piano that day, though he could not now remember where he went.

Eduardo, it turned out, was suited to studying law. He had always been diligent and high scoring, but he did not have that easygoing sheen that made people want to think well or expect much of him; he had never managed to effortlessly inspire confidence or lust. There was something about him that was too solicitous—it was subtle as a pheromone and just as permanent; it made people understand that they could ignore him and get away with it. Eduardo’s freakishly good memory did not help matters. Growing up, he had often surprised peers he barely knew by revealing his shockingly accurate retention of any scrap of information they’d volunteered the first time they’d met him, which occasion they invariably could not recall. Children reacted to this party trick with some bemusement, since their worldviews were not really at odds with the notion that everyone around them might somehow know who they were. As he grew older, however, Eduardo learned that mature narcissism responded with more suspicion: People tended to assume that Eduardo’s attention was particular to them, and he watched as their eyes narrowed and they wondered, visibly unnerved, just what exactly he might be after.

Still, Eduardo excelled in the clean realms—standardized testing, blind admissions, paper applications—where personality was scoured away; where memory was a strength, not a weakness. And it was these successes that delivered him to the University of Buenos Aires School of Law, where he finally learned—not in the classroom, but the bars—how to effectively wield his memory. Women, he learned, could be made to feel that Eduardo had a depth and singularity of feeling for them, whether he did or not. Men, as long as Eduardo used the right tone, could be made to feel quietly flattered and impressive. No matter how people felt about Eduardo, they usually left Eduardo’s company feeling faintly good about themselves. And Eduardo quickly saw that this was what mattered—that that slight untraceable rosy glow was the important emotional takeaway, even if it had nothing to do with Eduardo at all. He would never be particularly attractive or charismatic or possessed of the kind of authority that commanded attention. But he could make anybody he met feel that they were. And this, Eduardo saw, could leverage a power that was subtler and, depending on the situation, more potent than what was lost.

Читать дальше