He told Bill that humanity deserved to die horribly, since it had behaved so cruelly and wastefully on a planet so sweet. “We’re all Heliogabalus, Bill,” he would say. This was the name of a Roman emperor who had a sculptor make a hollow, life-size iron bull with a door on it. The door could be locked from the outside. The bull’s mouth was open. That was the only other opening to the outside.

Heliogabalus would have a human being put into the bull through the door, and the door would be locked. Any sounds the human being made in there would come out of the mouth of the bull. Heliogabalus would have guests in for a nice party, with plenty of food and wine and beautiful women and pretty boys—and Heliogabalus would have a servant light kindling. The kindling was under dry firewood—which was under the bull.

Trout did another thing which some people might have considered eccentric: he called mirrors leaks. It amused him to pretend that mirrors were holes between two universes.

If he saw a child near a mirror, he might wag his finger at a child warningly, and say with great solemnity, “Don’t get too near that leak. You wouldn’t want to wind up in the other universe, would you?”

Sometimes somebody would say in his presence, “Excuse me, I have to take a leak.” This was a way of saying that the speaker intended to drain liquid wastes from his body through a valve in his lower abdomen.

And Trout would reply waggishly, “Where I come from, that means you’re about to steal a mirror.”

And so on.

By the time of Trout’s death, of course, everybody called mirrors leaks. That was how respectable even his jokes had become.

In 1972, Trout lived in a basement apartment in Cohoes, New York. He made his living as an installer of aluminum combination storm windows and screens. He had nothing to do with the sales end of the business—because he had no charm. Charm was a scheme for making strangers like and trust a person immediately, no matter what the charmer had in mind.

Dwayne Hoover had oodles of charm.

I can have oodles of charm when I want to.

A lot of people have oodles of charm.

Trout’s employer and co-workers had no idea that he was a writer. No reputable publisher had ever heard of him, for that matter, even though he had written one hundred and seventeen novels and two thousand short stories by the time he met Dwayne.

He made carbon copies of nothing he wrote. He mailed off manuscripts without enclosing stamped, self-addressed envelopes for their safe return. Sometimes he didn’t even include a return address. He got names and addresses of publishers from magazines devoted to the writing business, which he read avidly in the periodical rooms of public libraries. He thus got in touch with a firm called World Classics Library, which published hard-core pornography in Los Angeles, California. They used his stories, which usually didn’t even have women in them, to give bulk to books and magazines of salacious pictures.

They never told him where or when he might expect to find himself in print. Here is what they paid him: doodley-squat.

They didn’t even send him complimentary copies of the books and magazines in which he appeared, so he had to search them out in pornography stores. And the titles he gave to his stories were often changed. “Pan Galactic Straw-boss,” for instance, became “Mouth Crazy.”

Most distracting to Trout, however, were the illustrations his publishers selected, which had nothing to do with his tales. He wrote a novel, for

instance, about an Earthling named Delmore Skag, a bachelor in a neighborhood where everybody else had enormous families. And Skag was a scientist, and he found a way to reproduce himself in chicken soup. He would shave living cells from the palm of his right hand, mix them with the soup, and expose the soup to cosmic rays. The cells turned into babies which looked exactly like Delmore Skag.

Pretty soon, Delmore was having several babies a day, and inviting his neighbors to share his pride and happiness. He had mass baptisms of as many as a hundred babies at a time. He became famous as a family man.

And so on.

Skag hoped to force his country into making laws against excessively large families, but the legislatures and the courts declined to meet the problem head-on. They passed stern laws instead against the possession by unmarried persons of chicken soup.

And so on.

The illustrations for this book were murky photographs of several white women giving blow jobs to the same black man, who, for some reason, wore a Mexican sombrero.

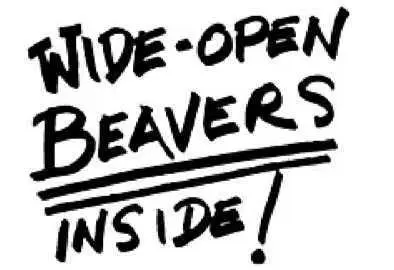

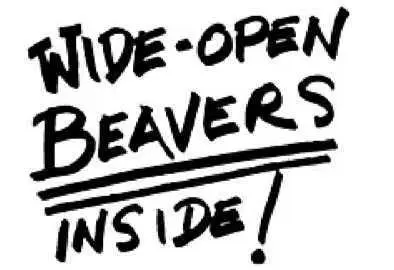

At the time he met Dwayne Hoover, Trout’s most widely-distributed book was Plague on Wheels. The publisher didn’t change the title, but he obliterated most of it and all of Trout’s name with a lurid banner which made this promise:

A wide-open beaver was a photograph of a woman not wearing underpants, and with her legs far apart, so that the mouth of her vagina could be seen. The expression was first used by news photographers, who often got to see up women’s skirts at accidents and sporting events and from underneath fire escapes and so on. They needed a code word to yell to other newsmen and friendly policemen and firemen and so on, to let them know what could be seen, in case they wanted to see it. The word was this: “Beaver!”

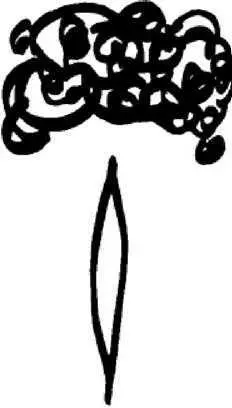

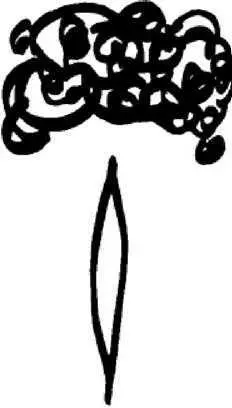

A beaver was actually a large rodent. It loved water, so it built dams. It looked like this:

The sort of beaver which excited news photographers so much looked like this:

This was where babies came from.

When Dwayne was a boy, when Kilgore Trout was a boy, when I was a boy, and even when we became middle-aged men and older, it was

the duty of the police and the courts to keep representations of such ordinary apertures from being examined and discussed by persons not engaged in the practice of medicine. It was somehow decided that wide-open beavers, which were ten thousand times as common as real beavers, should be the most massively defended secret under law.

So there was a madness about wide-open beavers. There was also a madness about a soft, weak metal, an element, which had somehow been declared the most desirable of all elements, which was gold.

And the madness about wide-open beavers was extended to underpants when Dwayne and Trout and I were boys. Girls concealed their underpants at all costs, and boys tried to see their underpants at all costs.

Female underpants looked like this:

One of the first things Dwayne learned in school as a little boy, in fact, was a poem he was supposed to scream in case he saw a girl’s underpants by accident in the playground. Other students taught it to him. This was it:

I see England,

I see France;

I see a little girl’s Underpants!

When Kilgore Trout accepted the Nobel Prize for Medicine in 1979, he declared: “Some people say there is no such thing as progress. The fact that human beings are now the only animals left on Earth, I confess, seems a confusing sort of victory. Those of you familiar with the nature of my earlier published works will understand why I mourned especially when the last beaver died.

Читать дальше