So Sacred Miracle Cave had become a part of the past.

As an old, old man, Trout would be asked by Dr. Thor Lembrig, the Secretary-General of the United Nations, if he feared the future. He would give this reply:

“Mr. Secretary-General, it is the past which scares the bejesus out of me.”

Dwayne Hoover was only four miles away. He was sitting alone on a zebra-skin banquette in the cocktail lounge of the new Holiday Inn. It was dark in there, and quiet, too. The glare and uproar of rush hour traffic on the Interstate was blocked out by thick drapes of crimson velvet. On each table was a hurricane lamp with a candle inside, although the air was still.

On each table was a bowl of dry-roasted peanuts, too, and a sign which allowed the staff to refuse service to anyone who was inharmonious with the mood of the lounge. Here is what it said:

Bunny Hoover was controlling the piano. He had not looked up when his father came in. Neither had his father glanced in his direction.

They had not exchanged greetings for many years.

Bunny went on playing his white man’s blues. They were slow and tinkling, with capricious silences here and there. Bunny’s blues had some of the qualities of a music box, a tired music box. They tinkled, stopped, then reluctantly, torpidly, they managed a few tinkles more.

Bunny’s mother used to collect tinkling music boxes, among other things.

Listen: Francine Pefko was at Dwayne’s automobile agency next door. She was catching up on all the work she should have done that afternoon. Dwayne would beat her up very soon.

And the only other person on the property with her as she typed and filed was Wayne Hoobler, the black parolee, who still lurked among the used cars. Dwayne would try to beat him up, too, but Wayne was a genius at dodging blows.

Francine was pure machinery at the moment, a machine made of meat—a typing machine, a filing machine.

Wayne Hoobler, on the other hand, had nothing machine-like to do. He ached to be a useful machine. The used cars were all locked up tight for the night. Now and then aluminum propellors on a wire overhead would be turned by a lazy breeze, and Wayne would respond to them as best he could. “Go,” he would say to them. “Spin ‘roun’.”

He established a sort of relationship with the traffic on the Interstate, too, appreciating its changing moods. “Everybody goin’ home,” he said during the rush hour jam. “Everybody home now,” he said later on, when the traffic thinned out. Now the sun was going down.

“Sun goin’ down,” said Wayne Hoobler. He had no clues as to where to go next. He supposed without minding much that he might die of exposure that night. He had never seen death by exposure, had never been threatened by it, since he had so seldom been out-of-doors. He knew of death by exposure because the papery voice of the little radio in his cell told of people’s dying of exposure from time to time.

He missed that papery voice. He missed the clash of steel doors. He missed the bread and the stew and the pitchers of milk and coffee. He missed fucking other men in the mouth and the asshole, and being facked in the mouth and the asshole, and jerking off—and fucking cows in the prison dairy, all events in a normal sex life on the planet, as far as he knew.

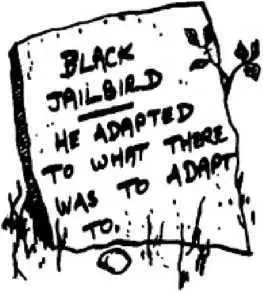

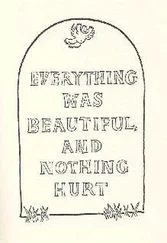

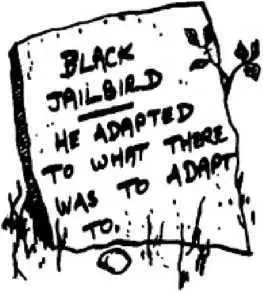

Here would be a good tombstone for Wayne Hoobler when he died:

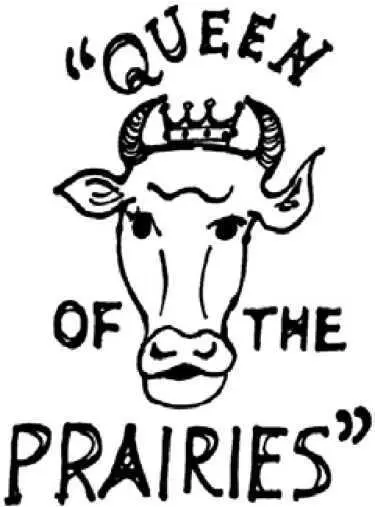

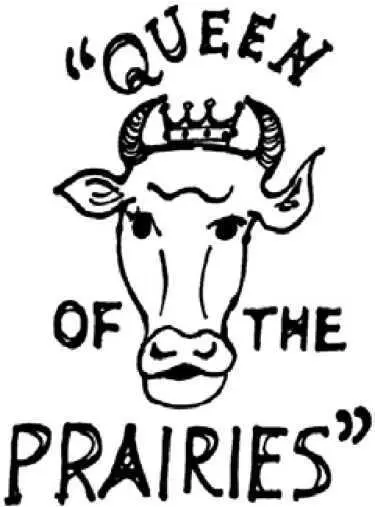

The dairy at the prison provided milk and cream and butter and cheese and ice cream not only for the prison and the County Hospital. It sold its products to the outside world, too. Its trademark didn’t mention prison. This was it:

Wayne couldn’t read very well. The words Hawaii and Hawaiian, for instance, appeared in combination with more familiar words and symbols in signs painted on the windows of the showroom and on the windshields of some used cars. Wayne tried to decode the mysterious words phonetically, without any satisfaction. “Wahee-io,” he would say, and “Hoo-he-woo-hi,” and so on.

Wayne Hoobler smiled now, not because he was happy but because, with so little to do, he thought he might as well show off his teeth.

They were excellent teeth. The Adult Correctional Institution at Shepherdstown was proud of its dentistry program.

It was such a famous dental program, in fact, that it had been written up in medical journals and in the Reader’s Digest, which was the dying planet’s most popular magazine. The theory behind the program was that many ex-convicts could not or would not get jobs because of their appearances, and good looks began with good teeth.

The program was so famous, in fact, that police even in neighboring states, when they picked up a poor man with expensively maintained teeth, fillings and bridgework and all that, were likely to ask him, “All right, boy—how many years you spend in Shepherdstown?”

Wayne Hoobler heard some of the orders which a waitress called to the bartender in the cocktail lounge. Wayne heard her call, “Gilbey’s and quinine, with a twist.” He had no idea what that was—or a Manhattan or a brandy Alexander or a sloe gin fizz. “Give me a Johnnie Walker Rob Roy,” she called, “and a Southern Comfort on the rocks, and a Bloody Mary with Wolfsichmidt’s.”

Wayne’s only experiences with alcohol had had to do with drinking cleaning fluids and eating shoe polish and so on. He had no fondness for alcohol.

“Give me a Black and White and water,” he heard the waitress say, and Wayne should have pricked up his ears at that. That particular drink wasn’t for any ordinary person. That drink was for the person who had created all Wayne’s misery to date, who could kill him or make him a millionaire or send him back to prison or do whatever he damn pleased with Wayne. That drink was for me.

I had come to the Arts Festival incognito. I was there to watch a confrontation between two human beings I had created: Dwayne Hoover and Kilgore Trout. I was not eager to be recognized. The waitress lit the hurricane lamp on my table. I pinched out the flame with my fingers. I had bought a pair of sunglasses at a Holiday Inn outside of Ashtabula, Ohio, where I spent the night before. I wore them in the darkness now. They looked like this:

The lenses were silvered, were mirrors to anyone looking my way. Anyone wanting to know what my eyes were like was confronted with his or her own twin reflections. Where other people in the cocktail lounge had eyes, I had two holes into another universe. I had leaks.

There was a book of matches on my table, next to my Pall Mall cigarettes.

Here is the message on the book of matches, which I read an hour and a half later, while Dwayne was beating the daylights out of Francine Pefko:

“It’s easy to make $100 a week in your spare time by showing comfortable, latest style Mason shoes to your friends. EVERYBODY goes for Mason shoes with their many special comfort features! We’ll send FREE moneymaking kit so you can run your business from home. We’ll even tell you how you can earn shoes FREE OF COST as a bonus for taking profitable orders!”

Читать дальше