Lyle told Dwayne about an experiment he and Kyle had performed the night before. They had gone into the cave with their identical Browning Automatic Shotguns, and they had opened fire on the advancing wall of bubbles.

“They let loose a stink you wouldn’t believe,” said Lyle. He said it smelled like athlete’s foot. “It drove me and Kyle right out of there. We run the ventilating system for an hour, and then we went back in. The paint was blistered on Moby Dick. He ain’t even got eyes anymore.” Moby Dick used to have long-lashed blue eyes as big as dinner plates.

“The organ turned black, and the ceiling turned a kind of dirty yellow,” said Lyle. “You can’t hardly see the Sacred Miracle no more.”

The organ was the Pipe Organ of the Gods, a thicket of stalactites and stalagmites which had grown together in one corner of the Cathedral. There was a loudspeaker in back of it, through which music for weddings and funerals was played. It was illuminated by electric lights, which changed colors all the time.

The Sacred Miracle was a cross on the ceiling of the Cathedral. It was formed by the intersection of two cracks. “It never was real easy to see,” said Lyle, speaking of the cross. “I ain’t even sure it’s there anymore.” He asked Dwayne’s permission to order a load of cement. He wanted to plug up the passage between the stream and the Cathedral.

“Just forget about Moby Dick and Jesse James and the slaves and all that,” said Lyle, “and save the Cathedral .”

Jesse James was a skeleton which Dwayne’s stepfather had bought from the estate of a doctor back during the Great Depression. The bones of its right hand mingled with the rusted parts of a.45 caliber revolver. Tourists were told that it had been found that way, that it probably belonged to some railroad robber who had been trapped in the cave by a rockslide.

As for the slaves: these were plaster statues of black men in a chamber fifty feet down the corridor from Jesse James. The statues were removing one another’s chains with hammers and hacksaws. Tourists were told that real slaves had at one time used the cave after escaping to freedom across the Ohio River.

The story about the slaves was as fake as the one about Jesse James. The cave wasn’t discovered until 1937, when a small earthquake opened it up a crack. Dwayne Hoover himself discovered the crack, and then he and his stepfather opened it with crowbars and dynamite. Before that, not even small animals had been in there.

The only connection the cave had with slavery was this: the farm on which it was discovered was started by an exslave, Josephus Hoobler. He was freed by his master, and he came north and started the farm. Then he went back and bought his mother and a woman who became his wife.

Their descendants continued to run the farm until the Great Depression, when the Midland County Merchants Bank foreclosed on the mortgage. And then Dwayne’s stepfather was hit by an

automobile driven by a white man who had bought the farm. In an out-of-court settlement for his injuries, Dwayne’s stepfather was given what he called contemptuously “. . . a God damn Nigger farm.”

Dwayne remembered the first trip the family took to see it. His father ripped a Nigger sign off the Nigger mailbox, and he threw it into a ditch. Here is what it said:

The truck carrying Kilgore Trout was in West Virginia now. The surface of the State had been demolished by men and machinery and explosives in order to make it yield up its coal. The coal was mostly gone now. It had been turned into heat.

The surface of West Virginia, with its coal and trees and topsoil gone, was rearranging what was left of itself in conformity with the laws of gravity. It was collapsing into all the holes which had been dug into it. Its mountains, which had once found it easy to stand by themselves, were sliding into valleys now.

The demolition of West Virginia had taken place with the approval of the executive, legislative, and judicial branches of the State Government, which drew their power from the people.

Here and there an inhabited dwelling still stood.

Trout saw a broken guardrail ahead. He gazed into a gully below it, saw a 1968 Cadillac El Dorado capsized in a brook. It had Alabama license plates. There were also several old home appliances in the brook—stoves, a washing machine, a couple of refrigerators.

An angel-faced white child, with flaxen hair, stood by the brook. She waved up at Trout. She clasped an eighteenounce bottle of Pepsi-Cola to her breast.

Trout asked himself out loud what the people did for amusement, and the driver told him a queer story about a night he spent in West Virginia, in the cab of his truck, near a windowless building which droned monotonously.

“I’d see folks go in, and I’d see folks come out,” he said, “but I couldn’t figure out what kind of a machine it was that made the drone. The building was a cheap old frame thing set up on cement blocks, and it was out in the middle of nowhere. Cars came and went, and the folks sure seemed to like whatever was doing the droning,” he said.

So he had a look inside. “It was full of folks on rollerskates,” he said. “They went around and around. Nobody smiled. They just went around and around.”

He told Trout about people he’d heard of in the area who grabbed live copperheads and rattlesnakes during church services, to show how much they believed that Jesus would protect them.

“Takes all kinds of people to make up a world,” said Trout.

Trout marveled at how recently white men had arrived in West Virginia, and how quickly they had demolished it—for heat.

Now the heat was all gone, too—into outer space, Trout supposed. It had boiled water, and the steam had made steel windmills whiz around and around. The windmills had made rotors in generators whiz around and around. America was jazzed with electricity for a while. Coal had also powered old-fashioned steamboats and choo-choo trains.

Choo-choo trains and steamboats and factories had whistles which were blown by steam when Dwayne Hoover and Kilgore Trout and I were boys—when our fathers were boys, when our grandfathers were boys. The whistles looked like this:

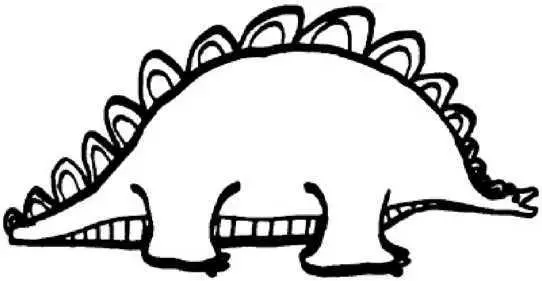

Steam from water boiled by burning coal was sent raging through the whistles, which made harshly beautiful laments, as though they were the voice boxes of mating or dying dinosaurs—cries such as woooooooo-uh, wooooo-uh, and torrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrnnnnnnnnnnnn , and so on.

A dinosaur was a reptile as big as a choo-choo train. It looked like this:

It had two brains, one for its front end and one for its rear end. It was extinct. Both brains combined were smaller than a pea. A pea was a legume which looked like this:

Coal was a highly compressed mixture of rotten trees and flowers and bushes and grasses and so on, and dinosaur excrement.

Kilgore Trout thought about the cries of steam whistles he had known, and about the destruction of West Virginia, which made their songs possible. He supposed that the heartrending cries had fled into outer space, along with the heat. He was mistaken.

Читать дальше