Kurt Vonnegut - Hocus Pocus

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Kurt Vonnegut - Hocus Pocus» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Hocus Pocus

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Hocus Pocus: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Hocus Pocus»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Hocus Pocus — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Hocus Pocus», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“There is much I could probably forgive, if somebody put a gun to my head, Professor Hartke,” he said, “but not what you did to my son.” He himself was no Tarkingtonian. He was a graduate of the Harvard Business School and the London School of Economics.

“Fred?” I said.

“In case you haven’t noticed,” he said, “I have only 1 son in Tarkington. I have only 1 son anywhere.” Presumably this I son, without having to lift a finger, would himself 1 day have $1,000,000,000.

“What did I do to Fred?” I said.

“You know what you did to Fred,” he said.

What I had done to Fred was catch him stealing a Tarkington beer mug from the college bookstore. What Fred Stone did was beyond mere stealing. He took the beer mug off the shelf, drank make-believe toasts to me and the cashier, who were the only other people there, and then walked out.

I had just come from a faculty meeting where the campus theft problem had been discussed for the umpteenth time. The manager of the bookstore told us that only one comparable institution had a higher percentage of its merchandise stolen than his, which was the Harvard Coop in Cambridge.

So I followed Fred Stone out to the Quadrangle. He was headed for his Kawasaki motorcycle in the student parking lot. I came up behind him and said quietly, with all possible politeness, “I think you should put that beer mug back where you got it, Fred. Either that or pay for it.”

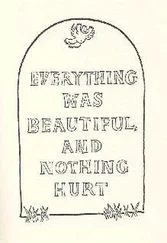

“Oh, yeah?” he said. “Is that what you think?” Then he smashed the mug to smithereens on the rim of the Vonnegut Memorial Fountain. “If that’s what you think,” he said, “then you’re the one who should put it back.”

I reported the incident to Tex Johnson, who told me to forget it.

But I was mad. So I wrote a letter about it to the boy’s father, but never got an answer until the Board meeting.

“I can never forgive you for accusing my son of theft,” the father said. He quoted Shakespeare on behalf of Fred. I was supposed to imagine Fred’s saying it tome. ~

“‘Who steals my purse steals trash; ‘tis something, nothing,’ “he said.” ‘ ‘Twas mine, ‘tis his, and has been slave to thousands,’ “ he went on, “‘but he that filches from me my good name robs me of that Which not enriches him and makes me poor indeed.’”

“If I was wrong, sir, I apologize,” I said.

“Too late,” he said.

17

There was 1 Trustee I was sure was my friend. He would have found what I said on tape funny and interesting. But he wasn’t there. His name was Ed Bergeron, and we had had a lot of good talks about the deterioration of the environment and the abuses of trust in the stock market and the banking industry and so on. He could top me for pessimism any day.

His wealth was as old as the Moellenkamps’, and was based on ancestral oil fields and coal mines and railroads which he had sold to foreigners in order to devote himself full-time to nature study and conservation. He was President of the Wildlife Rescue Federation, and his photographs of wildlife on the Galapagos Islands had been published in National Geographic. The magazine gave him the cover, too, which showed a marine iguana digesting seaweed in the sunshine, right next to a skinny penguin who was no doubt having thoughts about entirely different issues of the day, whatever was going on that day.

Not only was Ed Bergeron my doomsday pal. He was also a veteran of several debates about environmentalism with Jason Wilder on Wilder’s TV show. I haven’t found a tape of any of those ding-dong head-to-heads in this library, but there used to be 1 at the prison. It would bob up about every 6 months on the TV sets there, which were running all the time.

In it, I remember, Wilder said that the trouble with conservationists was that they never considered the costs in terms of jobs and living standards of eliminating fossil fuels or doing something with garbage other than dumping it in the ocean, and so on.

Ed Bergeron said to him, “Good! Then I can write the epitaph for this once salubrious blue-green orb.” He meant the planet.

Wilder gave him his supercilious, vulpine, patronizing, silky debater’s grin. “A majority of the scientific community,” he said, “would say, if I’m not mistaken, that an epitaph would be premature by several thousand years.” That debate took place maybe 6 years before I was fired, which would be back in 1985, and I don’t know what scientific community he was talking about. Every kind of scientist, all the way down to chiropractors and podiatrists, was saying we were killing the planet fast.

“You want to hear the epitaph?” said Ed Bergeron.

“If we must,” said Wilder, and the grin went on and on. “I have to tell you, though, that you are not the first person to say the game was all over for the human race. I’m sure that even in Egypt before the first pyramid was constructed, there were men who attracted a following by saying, ‘It’s all over now.’”

“What is different about now as compared with Egypt before the first pyramid was built—” Ed began.

“And before the Chinese invented printing, and before Columbus discovered America,” Jason Wilder interjected.

“Exactly,” said Bergeron.

“The difference is that we have the misfortune of knowing what’s really going on,” said Bergeron, “which is no fun at all. And this has given rise to a whole new class of preening, narcissistic quacks like yourself who say in the service of rich and shameless polluters that the state of the atmosphere and the water and the topsoil on which all life depends is as debatable as how many angels can dance on the fuzz of a tennis ball.”

He was angry.

When this old tape was played at Athena before the great escape, it kindled considerable interest. I watched it and listened with several students of mine. Afterward one of them said to me, “Who right, Professor—beard or mustache?” Wilder had a mustache. Bergeron had a beard.

“Beard,” I said.

That may have been almost the last word I said to a convict before the prison break, before my mother-in-law decided that it was at last time to talk about her big pickerel.

Bergeron’s epitaph for the planet, I remember, which he said should be carved in big letters in a wall of the Grand Canyon for the flying-saucer people to find, was this:

WE COULD HAVE SAVED IT,

BUT WE WERE TOO DOGGONE CHEAP.

Only he didn’t say “doggone.”

But I would never see or hear from Ed Bergeron again. He resigned from the Board soon after I was fired, and so would miss being taken hostage by the convicts. It would have been interesting to hear what he had to say to and about that particular kind of captor. One thing he used to say to me, and to a class of mine he spoke to one time, was that man was the weather now. Man was the tornadoes, man was the hailstones, man was the floods. So he might have said that Scipio was Pompeii, and the escapees were a lava flow.

He didn’t resign from the Board on account of my firing. He had at least two personal tragedies, one right on top of the other. A company he inherited made all sorts of products out of asbestos, whose dust proved to be as carcinogenic as any substance yet identified, with the exception of epoxy cement and some of the radioactive stuff accidentally turned loose in the air and aquifers around nuclear weapons factories and power plants. He felt terrible about this, he told me, although he had never laid eyes on any of the factories that made the stuff. He sold them for practically nothing, since the company in Singapore that bought them got all the lawsuits along with the machinery and buildings, and an inventory of finished materials which was huge and unsalable in this country. The people in Singapore did what Ed couldn’t bring himself to do, which was to sell all those floor tiles and roofing and so on to emerging nations in Africa.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Hocus Pocus»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Hocus Pocus» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Hocus Pocus» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.