“What were the invaders like?” asked Selvaggia.

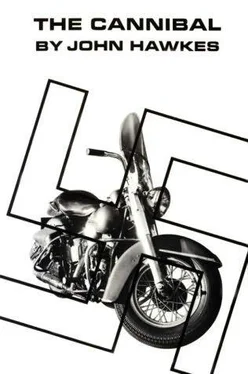

“They were bad people, but they didn’t stay long.” The child had been protected from their sight the week that the Americans had stopped in the town; now they had scurried on to the further cities, and only a man on a motorcycle came occasionally to Spitzen-on-the-Dein . His saddlebags were full and his handsome machine roared across untraveled roads with authority. But his face was covered with goggles and Selvaggia had only seen him bouncing quickly, noisily, through the streets.

“You shouldn’t even think about them,” said Jutta, and she vaguely hoped that her child would not.

In the sunlight Jutta’s hair was not so pretty, pinhead eyelets of dirt were on her nose, spots in the loose dress had run, her legs were large and stiff under the re-stitched swinging hem. Her daughter’s face narrowed to a thin point at the chin and it seemed likely that the child would never have breasts. Under the narrow fish-bone chest where they might have been, her heart beat autonomously, unaffected by the sight of the hill of sliding moist clay. The tar-paper houses on top of the hill were sunken at the ends, jewels of tin cans littered the indefinable yards without lawns or bushes, and hostile eyes watched mother and daughter from behind the fallen poles. A dense unpleasant smell arose from beneath the ruins about two standing walls and drifted out across the narrow road on the chilly wind. “Tod,” said the mother under her breath. Side by side they stared down the uneven grey slopes to where the brick-red remains of the institution sprawled in the glittering light.

“What’s that?” asked Selvaggia.

“That’s where they used to keep the crazy people.” The pointed head nodded.

Many, many years before, a woman doctor had spoken to Balamir in those same buildings:

“What’s your name?”

“Will you tell me what day this is?”

“Weiss nicht .”

“Do you know what year this is?”

“Do you know where you are?”

“Weiss nicht .”

“You’re going to have a good time here.”

“Weiss nicht, weiss nicht! ”

As they went down the hill the bright sun had become more cold, their feet were wet, and they had been very glad to get back to the quiet of the rooms.

The yellow walls flickered as the electric globe dimmed, rose, dimmed but did not go out, as the generator sputtered and continued to drone far beneath us in Balamir’s basement. Below her stomach the white flesh puffed into a gentle mound, then dissolved into the sheets, while her fingers against my arm traced over the silken outlines of a previous wound. Her mind could only see as far as immediate worry for her son, never awoke in anticipation for the after-dark, or in fear to rise in light; and as the thought of the child slipped downwards and ceased, every moment hence was plotted by actions circled about in the room. She tapped my arm as if to say, “I get up, but don’t bother,” and left the couch, the top of the robe swinging behind from the waist. She poured the cold water into the basin, washed carefully and left the water to settle. In the other room to get a light for my cigarette, she said, “Schlaf’,” to her daughter at the window and returned with the lighted splinter. In his sleep the Census-Taker heard a few low mournful notes of a horn, as if an echo, in a deeper register, of the bugles that used to blast fitfully out among the stunted trees in the low fields on the south edge of town. Once, twice, then Herr Stintz stood his instrument in a corner and sat alone in the dark on the floor below. The apartment on the second floor was dark.

“They’re dancing tonight,” I said, paper stuck to my lips, “let’s go, I still have a few hours.”

“Tanzen?”

“Yes. Let’s go, just for a while.”

She dressed in a pale blue gown that sparkled in the wrinkles, stepped into the shoes of yesterday’s walk and washed again. I wore no tie but buttoned the grey shirt up to my throat, rubbed my eyes, and reaching over, shook the Census-Taker by the foot. The hallway was completely black and ran with cold drafts. We went slowly from the fifth to the fourth, to the third, the second, the Census-Taker leaning with both arms on the rail.

“The Duke’s,” said Jutta, nodding.

“Ah, the Duke’s.”

The little girl heard the door slam shrilly far below her vigil at the window.

“What’s all this about dancing?” asked the Census-Taker, his hands held tightly over his ears from the cold, his raised elbows jerking in peculiar half-arcs with his stride. We walked quickly to the hill that rose much higher in the darkness.

At night the institution towered upward crookedly, and fanned out into a haphazard series of dropped terraces and barren rooms, suddenly twisted walls and sealed entrances, combed of reality, smothered out of all order by its overbearing size. We walked at an average pace, feeling for each other’s hands, unafraid of this lost architecture, unimpressed by the sound of our own feet. There was no food in the vaulted kitchens. Offices and conference rooms were stripped of pencils, records, leather cushions. Large patches of white wall were smeared with dilating lost designs of seeping water, and inner doors were smeared with chalk fragments of situation reports of the then anxious and struggling Allied armies. The institution was menacing, piled backwards on itself in chaotic slumber, and in segregated rooms, large tubs — long, fat and thick edges ringed with metal hooks that once held patients on their canvas cradles — had become sooted with grey, filled with fallen segments of plaster from the ceilings. Strange, unpursued animals now made their lairs in the corners of the dormitories where insulin had once flowed and produced cures. And this was where the riot had taken place.

Each of us walking through this liberated and lonely sanctum, past its now quiet rooms, heard fragments of recognition in the bare trees. For once it had been both awesome and yet holy, having caused in each of us, silent marchers, at one time or another, a doubt for his own welfare and also a momentary wonder at the way they could handle all those patients. Once the days had been interrupted by the very hours and the place had passed by our minds new and impressive with every stroke. But now the days were uninterrupted and the shadows from the great felled wings sprawled colorless and without any voice about our ever moving feet. Then, scudding away through the maze, new, unkempt and artificial, the low clapboard storehouse emerged, champing of strange voices. It heeled, squat beneath its own glimmers of weak light, a small boarded place of congregation, hounded by the darkness of the surrounding buildings.

Without slacking pace, we neared the din and fray above the scratching needle, the noise of women dancing with women, and men with men, shadows skipping without expression across the blind of a half-opened door. They ceased to whirl only for a moment and then the feet shuffled again over the floor boards, and we, walking towards the building, smelled the odor of damp cinders and felt for a moment the black leaves settle about our ankles.

Jutta, the Census-Taker and myself, emerging from flat darkness into light that was only a shade brighter, bowed our heads, fending off the tinted glare that filled the spaces between the rigid dancers. Close together, we stood for a moment sunken in the doorway. Figures stepped forwards, backwards, caught in a clockwork of custom, a way of moving that was almost forgotten. Gathered in the storehouse, back to back, face measured to face, recalled into the group and claiming name instead of number, each figure, made responsible, appeared with the same sackcloth idleness as Jutta. They swung out of the mist and appeared with pocketed cheeks and shaven heads. They seemed to dance with one leg always suspended, small white bodies colliding like round seamless pods, and fingers entwined were twice as long as palms. They danced continuously forming patterns, always the same, of grey and pale blue. The beauties were already sick, and the word krank passed from group to group over devious tongues, like the grapevine current of fervent criminal words that slide through wasted penal colonies. The smallest women had the roundest legs that bounced against jutting knees, and the seams of their gowns were taken up with coarse thread. High above their shoulders towered their partners’ heads, loose, with cold whitening eyes, tongues the faded color of cheeks, curled back to the roots of forgotten words. Several girls were recently orphaned when Allied trucks, bringing German families back from hiding, had smashed, traveling too fast along the highway, and had scattered the old people like punched cows in the fields. Some of these danced together, stopping to see which way the other would turn.

Читать дальше