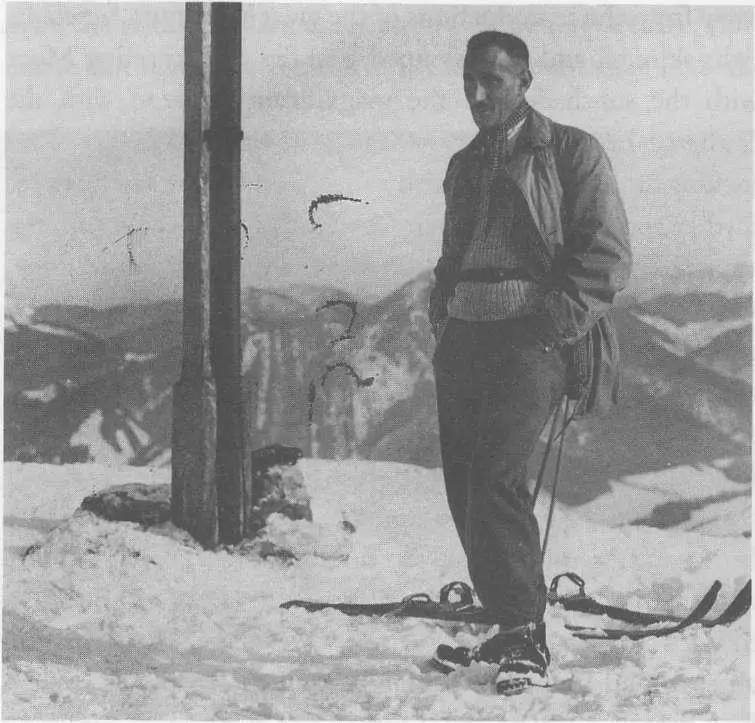

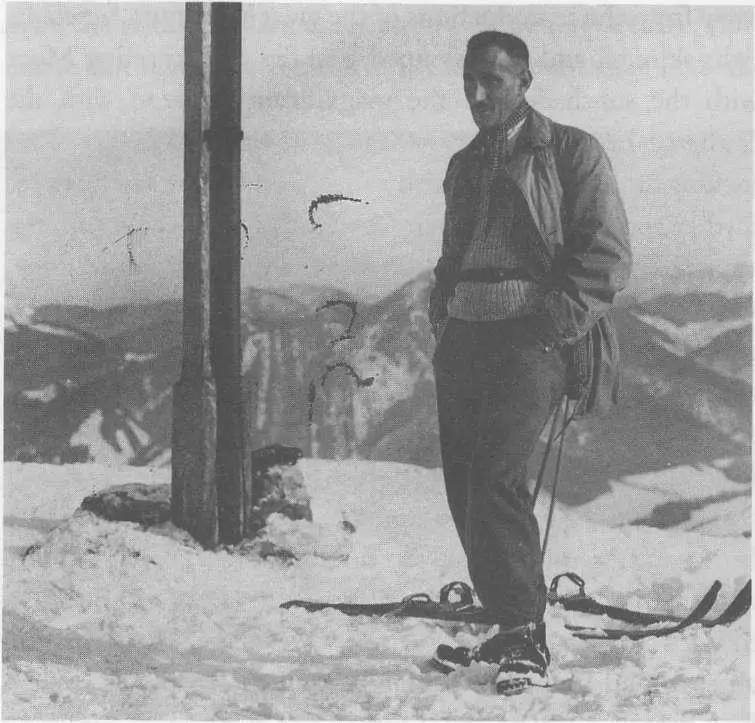

short. To me he said not a word about what he had seen and experienced. How much he told Mother, I do not know. Once more, in early 1939, we went to Lenggries for the skiing. It was my last time and I think it was Father's, too. I took a photo of him up on the Brauneck. It is one of the few that have survived from those years, said Ferber. Not long after our trip to Lenggries, Father managed to get a visa for me by bribing the English consul. Mother was counting on their both following me soon. Father was finally determined to leave the country, she said. They only had to make the necessary arrangements. So my things were packed, and on the 17th of May, Mothers fiftieth birthday, my parents took me to the airport. It was a fine, bright morning, and we drove from our house in Sternwartstrasse in Bogenhausen across the Isar, through the Englischer Garten along Tivolistrasse, across the Eisbach, which I still see as clearly as I did then, to Schwabing and then out of the city along Leopoldstrasse towards Oberwiesenfeld. The drive seemed endless to me, said Ferber, probably because none of us said a word. When I asked if he remembered saying goodbye to his parents at the airport, Ferber replied, after a long hesitation, that when he thought back to that May morning at Oberwiesenfeld he could not see his parents. He no longer knew what the last thing his mother or father had said to him was, or he to them, or whether he and his parents had embraced or not. He could still see his parents sitting in the back of the hired car on the drive out to Oberwiesenfeld, but he could not see them at the airport itself. And yet he could picture Oberwiesenfeld down to the last detail, and all these years had been able to envisualize it with that fearful precision, time and time again. The bright concrete strip in front of the open hangar and the deep dark inside it, the swastikas on the rudders of the aircraft, the fenced-off area where he had to wait with the other passengers, the privet hedge around the fence, the groundsman with his wheelbarrow, shovel and brush, the weather station boxes, which reminded him of bee-hives, the cannon at the airfield perimeter — he could see it all with painful clarity, and he could see himself walking across the short grass towards the white Lufthansa Junkers 52, which bore the name Kurt Wüsthoff and the number D—3051. I see myself mounting the wheeled wooden steps, said Ferber, and sitting down in the plane beside a woman in a blue Tyrolean hat, and I see myself looking out of the little square window as we raced across the big, green, deserted airfield, at a distant flock of sheep and the tiny figure of a shepherd. And then I see Munich slowly tilting away below me.

The flight in the JU52 took me only as far as Frankfurt, said Ferber, where I had to wait for several hours and clear customs. There, at Frankfurt am Main airport, my opened suitcase sat on an ink-stained table while a customs official, without touching a thing, stared into it for a very long time, as if the clothes which my mother had folded and packed in her distinctive, highly orderly way, the neatly ironed shirts or my Norwegian skiing jersey, might possess some mysterious significance. What I myself thought as I looked at my open suitcase, I no longer know; but now, when I think back, it feels as if I ought never to have unpacked it, said Ferber, covering his face with his hands. The BEA plane in which I flew on to London at about three that afternoon, he continued, was a Lockheed Electra. It was a fine flight. I saw Belgium from the air, the Ardennes, Brussels, the straight roads of Flanders, the sand dunes of Ostende, the coast, the white cliffs of Dover, the green hedgerows and hills south of London, and then, appearing on the horizon like a low grey range of hills, the island capital itself. We landed at half past five at Hendon airfield. Uncle Leo met me. We drove into the city, past endless rows of suburban houses so indistinguishable from one another that I found them depressing yet at the same time vaguely ridiculous. Uncle was living in a little emigre hotel in Bloomsbury, near the British Museum. My first night in England was spent in that hotel, on a peculiar, high-framed bed, and was sleepless not so much because of my distress as because of the way that one is pinned down, in English beds of that kind, by bedding which has been tucked under the mattress all the way round. So the next morning, the 18th of May, I was bleary-eyed and weary when I tried on my new school uniform at Baker's in Kensington, with my uncle — a pair of short black trousers, royal blue knee-length socks, a blazer of the same colour, an orange shirt, a striped tie, and a tiny cap that would not stay put on my full shock of hair no matter how I tried. Uncle, given the funds at his disposal, had found me a third-rate public school at Margate, and I believe that when he saw me kitted out like that he was as close to tears as I was when I saw myself in the mirror. And if the uniform felt like a fool's motley, expressly designed to heap scorn upon me, then the school itself, when we arrived there that afternoon, seemed like a prison or mental asylum. The circular bed of dwarf conifers in the curve of the drive, the grim facade capped by battlements of sorts, the rusty bell-pull beside the open door, the school janitor who came limping out of the darkness of the hall, the colossal oak stairwell, the coldness of all the rooms, the smell of coal, the incessant cooing of the decrepit pigeons that perched everywhere on the roof, and numerous other sinister details I no longer remember, conspired to make me think that I would go mad in next to no time in that establishment. It presently emerged, however, that the regime of the school — where I was to spend the next few years — was in fact fairly lax, sometimes to the point of anarchy. The headmaster and founder of the school, a man by the name of Lionel Lynch-Lewis, was a bachelor of almost seventy, invariably dressed in the most eccentric manner and scented with a discreet hint of lilac; and his staff, no less eccentric, more or less left the pupils, who were mainly the sons of minor diplomats from unimportant countries, or the offspring of other itinerants, to their own devices. Lynch-Lewis took the view that nothing was more damaging to the development of young adolescents than a regular school timetable. He maintained that one learnt best and most easily in one's free time. This attractive concept did in fact bear fruit for some of us, but others ran quite disturbingly wild as a result. As for the parrot-like uniform which we had to wear and which, it turned out, had been designed by Lynch-Lewis himself, it formed the greatest possible contrast to the rest of his pedagogical approach. At best, the outré riot of colour we were obliged to wear fitted in with the excessive emphasis placed by Lynch-Lewis on the cultivation of correct English, which in his view could mean only turn-of-the-century stage English. Not for nothing was it rumoured in Margate that our teachers were all, without exception, recruited from the ranks of actors who had failed, for whatever reason, in their chosen profession. Oddly enough, said Ferber, when I look back at my time in Margate I cannot say whether I was happy or unhappy, or indeed what I was. At any rate, the amoral code that governed life at school gave me a certain sense of freedom, such as I had not had till then — and, that being so, it grew steadily harder for me to write my letters home or to read the letters that arrived from home every fortnight. The correspondence became more of a chore, and when the letters stopped coming, in November 1941, I was relieved at first, in a way that now strikes me as quite terrible. Only gradually did it dawn on me that I would never again be able to write home; in fact, to tell the truth, I do not know if I have really grasped it to this day. But it now seems to me that the course of my life, down to the tiniest detail, was ordained not only by the deportation of my parents but also by the delay with which the news of their death reached me, news I could not believe at first and the meaning of which only sank in by degrees. Naturally, I took steps, consciously or unconsciously, to keep at bay thoughts of my parents' sufferings and of my own misfortune, and no doubt I succeeded sometimes in maintaining a certain equability by my self-imposed seclusion; but the fact is that that tragedy in my youth struck such deep roots within me that it later shot up again, put forth evil flowers, and spread the poisonous canopy over me which has kept me so much in the shade and dark in recent years.

Читать дальше