At every hour of the day and night, the Wadi Haifa was lit by flickering, glaringly bright neon light that permitted not the slightest shadow. When I think back to our meetings in Trafford Park, it is invariably in that unremitting light that I see Ferber, always sitting in the same place in front of a fresco painted by an unknown hand that showed a caravan moving forward from the remotest depths of the picture, across a wavy ridge of dunes, straight towards the beholder. The painter lacked the necessary skill, and the perspective he had chosen was a difficult one, as a result of which both the human figures and the beasts of burden were slightly distorted, so that, if you half shut your eyes, the scene looked like a mirage, quivering in the heat and light. And especially on days when Ferber had been working in charcoal, and the fine powdery dust had given his skin a metallic sheen, he seemed to have just emerged from the desert scene, or to belong in it. He himself once remarked, studying the gleam of graphite on the back of his hands, that in his dreams, both waking and by night, he had already crossed all the earth's deserts of sand and stone. But anyway, he went on, avoiding any further explanation, the darkening of his skin reminded him of an article he had recently read in the paper about silver poisoning, the symptoms of which were not uncommon among professional photographers. According to the article, the British Medical Associations archives contained the description of an extreme case of silver poisoning: in the 1930s there was a photographic lab assistant in Manchester whose body had absorbed so much silver in the course of a lengthy professional life that he had become a kind of photographic plate, which was apparent in the fact (as Ferber solemnly informed me) that the man's face and hands turned blue in strong light, or, as one might say, developed.

One summer evening in 1966, nine or ten months after my arrival in Manchester, Ferber and I were walking along the Ship Canal embankment, past the suburbs of Eccles, Patricroft and Barton upon Irwell on the other side of the black water, towards the setting sun and the scattered outskirts where occasional views opened up, affording an intimation of the marshes that extended there as late as the mid nineteenth century. The Manchester Ship Canal, Ferber told me, was begun in 1887 and completed in 1894. The work was mainly done by a continuously reinforced army of Irish navvies, who shifted some sixty million cubic metres of earth in that period and built the gigantic locks that would make it possible to raise or lower ocean-going steamers up to 150 metres long by five or six metres. Manchester was then the industrial Jerusalem, said Ferber, its entrepreneurial spirit and progressive vigour the envy of the world, and the completion of the immense canal project had made it the largest inland port on earth. Ships of the Canada & Newfoundland Steamship Company, the China Mutual Line, the Manchester Bombay General Navigation Company, and many other shipping lines, plied the docks near the city centre. The loading and unloading never stopped: wheat, nitre, construction timber, cotton, rubber, jute, train oil, tobacco, tea, coffee, cane sugar, exotic fruits, copper and iron °te, steel, machinery, marble and mahogany — everything,

in fact, that could possibly be needed, processed or made in a manufacturing metropolis of that order. Manchester's shipping traffic peaked around 1930 and then went into an irreversible decline, till it came to a complete standstill in the late Fifties. Given the motionlessness and deathly silence that lay upon the canal now, it was difficult to imagine, said Ferber, as we gazed back at the city sinking into the twilight, that he himself, in the postwar years, had seen the most enormous freighters on this water. They would slip slowly by, and as they approached the port they passed amidst houses, looming high above the black slate roofs. And in winter, said Ferber, if a ship suddenly appeared out of the mist when one least expected it, passed by soundlessly, and vanished once more in the white air, then for me, every time, it was an utterly incomprehensible spectacle which moved me deeply.

I no longer remember how Ferber came to tell me the extremely cursory version of his life that he gave me at that time, though I do remember that he was loath to answer the questions I put to him about his story and his early years. It was in the autumn of 1943, at the age of eighteen, that Ferber, then a student of art, first went to Manchester. Within months, in early 1944, he was called up. The only point of note concerning that first brief stay in Manchester, said Ferber, was the fact that he had lodged at 104, Palatine Road — the selfsame house where Ludwig Wittgenstein, then a twenty-year-old engineering student, had lived in 1908. Doubtless any retrospective connection with Wittgenstein was purely illusory, but it meant no less to him on that account, said Ferber. Indeed, he sometimes felt as if he were tightening his ties to those who had gone before; and for that reason, whenever he pictured the young Wittgenstein bent over the design of a variable combustion chamber, or test-flying a kite of his own construction on the Derbyshire moors, he was aware of a sense of brotherhood that reached far back beyond his own lifetime or even the years immediately before it. Continuing with his account, Ferber told me that after basic training at Catterick, in a God-forsaken part of north Yorkshire, he volunteered for a paratroop regiment, hoping that that way he would still see action before the end of the war, which was clearly not far off. Instead, he fell ill with jaundice, and was transferred to the convalescent home in the Palace Hotel at Buxton, and so his hopes were dashed. Ferber was compelled to spend more than six months at the idyllic Derbyshire spa town, recovering his health and consumed with rage, as he observed without explanation. It had been a terribly bad time for him, a time scarcely to be endured, a time he could not bear to say any more about. At all events, in early May 1945, with his discharge papers in

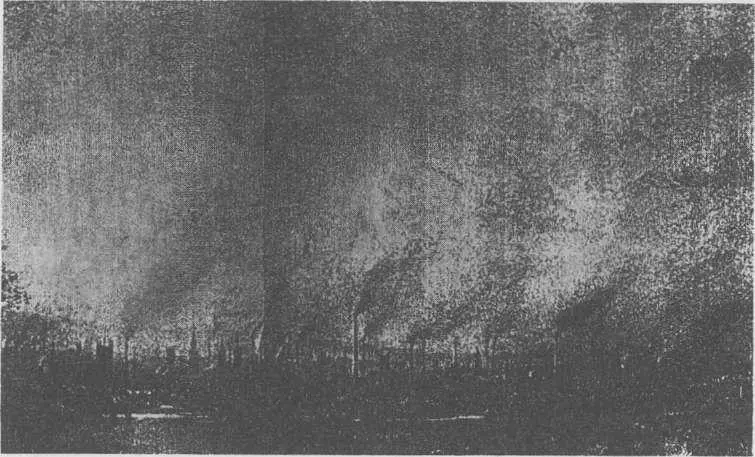

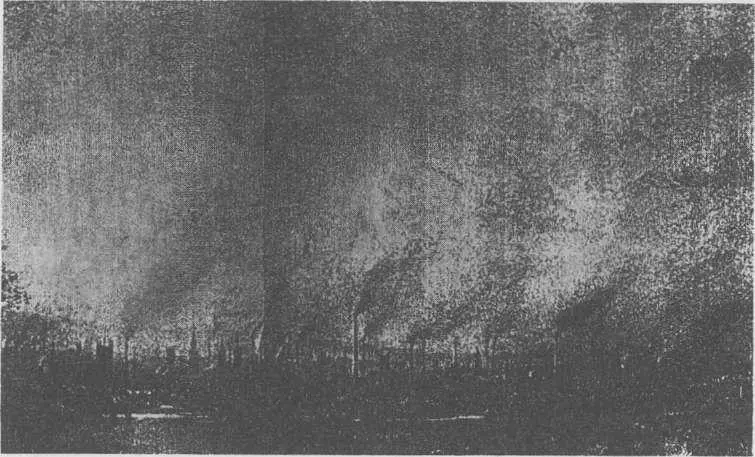

his pocket, he had walked the roughly forty kilometres to Manchester to resume his art studies there. He could still see, with absolute clarity, his descent from the fringes of the moorlands after his walk amidst the spring sunshine and showers. From a last bluff he had had a bird's eye view of the city spread out before him, the city where he was to live ever after. Contained by hills on three sides, it lay there as if in the heart of a natural amphitheatre. Over the flatland to the west, a curiously shaped cloud extended to the horizon, and the last rays of sunlight were blazing past its edges, and for a while lit up the entire panorama as if by firelight or Bengal flares. Not until this illumination died (said Ferber) did his eye roam, taking in the crammed and interlinked rows of houses, the textile mills and dying works, the gasometers, chemicals plants and factories of every kind, as far as what he took to be the centre of the city, where all seemed one solid mass of utter blackness, bereft of any further distinguishing features. The most impressive thing, of course, said Ferber, were all the chimneys that towered above the plain and the flat maze of

housing, as far as the eye could see. Almost every one of those chimneys, he said, has now been demolished or taken out of use. But at that time there were still thousands of them, side by side, belching out smoke by day and night. Those square and circular smokestacks, and the countless chimneys from which a yellowy-grey smoke rose, made a deeper impression on me when I arrived than anything else I had previously seen, said Ferber. I can no longer say exactly what thoughts the sight of Manchester prompted in me then, but I believe I felt I had found my destiny. And I also remember, he said, that when at last I was ready to go on I looked down once more over the pale green parklands deep down below, and, half an hour after sunset, saw a shadow, like the shadow of a cloud, flit across the fields — a herd of deer headed for the night.

Читать дальше