Church of Agony; to the south and west are the Armenian Orthodox Monastery of Mount Zion, the Protestant School, the Sisters of St Vincent, the Hospice of the Knights of St John, the Convent of the Sisters of St Clare, the Montefiore Hospice and the Moravian Lepers' Home. In the centre of the city there are the Church and Residence of the Latin Patriarch, the Dome of the Rock, the School of the Frères de la Doctrine Chrétienne, the school and printing works of the Franciscan Brotherhood, the Coptic Monastery, the German Hospice, the German Protestant Church of the Redeemer, the United Armenian Church of the Spasm (as it is called), the Couvent des Soeurs de Zion, the Austrian Hospital, the Monastery and Seminary of the Algerian Mission Brotherhood, the Church of Sant'Anna, the Jewish Hospice, the Ashkenazy and Sephardic Synagogues, and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, below the portal of which a misshapen little man with a cucumber of a nose offered us his services as a guide through the intricacies of the aisles and transepts, chapels, shrines and altars. He was wearing a bright yellow frock coat which to my mind dated far back into the last century, and his crooked legs were clad in what had once been a dragoon's breeches, with sky-blue piping. Taking tiny steps, always half turned to us, he danced ahead and talked nonstop in a language he probably thought to be German or English but which was in fact of his own invention and to me, at all events, quite incomprehensible. Whenever his eye fell on me I felt as despised and cold as a stray dog. Later, too, outside the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, a continuing feeling of oppressiveness and misery. No matter which direction we went in, we always came up at one of the steep ravines that crisscross the city, falling away to the valleys. By now the ravines have largely been filled with the rubbish of a thousand years, and everywhere liquid waste flows openly into them. As a result, the water of numerous springs has become undrink-able. The erstwhile pools of Siloam are no more than foul puddles and cesspits, a morass from which the miasma rises that causes epidemics to rage here almost every summer. Cosmo says repeatedly that he is utterly horrified by the city.

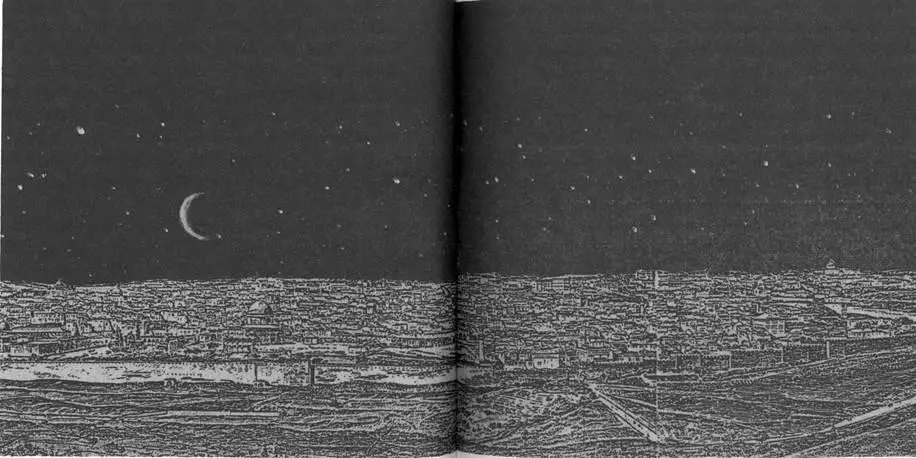

On the 27th of November Ambros notes that he has been to Raad's Photographic Studio in the Jaffa Road and has had his picture taken, at Cosmo's wish, in his new striped Arab robe. In the afternoon (he continues) out of the city to the Mount of Olives. We pass a withered vineyard. The soil beneath the black vines rust-coloured, exhausted and scorched. Scarcely a wild olive tree, a thorn bush, or a little hyssop. On the crest of the Mount of Olives runs a riding track. Beyond the valley of Jehoshaphat, where at the end of time, it is said, the entire human race will gather in the flesh, the silent city rises from the white limestone with its domes, towers and ruins. Over the rooftops not a sound, not a trace of smoke, nothing. Nowhere, as far as the eye can see, is there any sign of life, not an animal scurrying by, or even the smallest bird in flight. On dirait que cest la terre maudite. . On the other side, what must be more than three thousand feet below, the Jordan and part of the Dead Sea. The air is so bright, so thin and so clear that without thinking one might reach out a hand to touch the tamarisks down there on the river bank. Never before had we been washed in such a flood of light! A little further on, we found a place to rest in a mountain hollow where a stunted box tree and a few wormwood shrubs grow. We leant against the rock wall for a long time, feeling how everything gradually faded… In the evening, studied the guidebook I bought in Paris. In the past, it says, Jerusalem looked quite different. Nine tenths of the splendours of the world were to be found in this magnificent city. Desert caravans brought spices, precious stones, silk and gold. From the sea ports of Jaffa and Askalon, merchandise came up in abundance. The arts and commerce were in full flower. Before the walls, carefully tended gardens lay outspread, the valley of Jehoshaphat was canopied with cedars, there were streams, springs, fish pools, deep channels, and everywhere cool shade. And then came the age of destruction. Every settlement up to a four-hour journey away in every direction was destroyed, the irrigation systems were wrecked, and the trees and bushes were cut down, burnt and blasted, down to the very last stump. For years the Caesars deliberately made it impossible to live there, and in later times too Jerusalem was repeatedly attacked, liberated and pacified, until at last the desolation was complete and nothing remained of the matchless wealth of the Promised Land but dry stone and a remote idea in the heads of its people, now dispersed throughout the world.

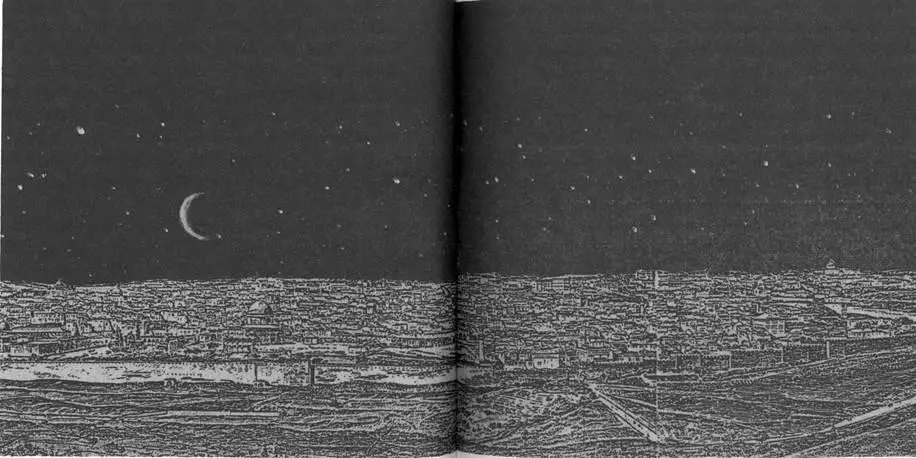

4th December: Last night dreamt that Cosmo and I crossed the glaring emptiness of the Jordan valley. A blind guide walks ahead of us. He points his staff to a dark spot on the horizon and cries out, several times, er-Riha, er-Riha. As we approach, er-Riha proves to be a dirty village with sand and dust swirling about it. The entire population has gathered on the edge of the village in the shade of a tumbledown sugar mill. One has the impression that they are nothing but beggars and footpads. A noticeable number are gouty, hunchbacked or disfigured. Others are lepers or have immense goitres. Now I see that all these people are from Gopprechts. Our Arab escorts fire their long rifles into the air. We ride past, and the people cast malevolent looks after us. At the foot of a low hill we pitch the black tents. The Arabs light a small fire and cook a dark green broth of Jew's mallow and mint leaves, and bring some of it over to us in tin bowls, with slices of lemon and crushed grain. Night falls rapidly. Cosmo lights the lamp and spreads out his map on the colourful carpet. He points to one of the many white spaces and says: We are now in Jericho. The oasis is a four-hour walk in length and a one-hour walk in breadth, and of a rare beauty per matched only by the paradisal orchard of Damascus merveilleux verger de Damas. The people here have all want. Whatever they sow grows immediately in this fertile soil. The glorious gardens flower forever. The gree corn sways in the bright palm groves. The fiery hea summer is made bearable by the many watercourses pastures, the crowns of the trees and the vine leaves ovej pathways. The winters are so mild that the people of blessèd land wear no more than a linen shirt, even wher mountains of Judaea, not far off, are white with sno 1Several blank pages follow the account of the drean er-Riha. During this time, Ambros must have been ch occupied with recruiting a small troop of Arabs and acqui the equipment and provisions needed for an expedition tc Dead Sea, for on the 16th of December he writes: Left c crowded Jerusalem with its hordes of pilgrims three days and rode down the Kidron Valley into the lowest regioi earth. Then, at the foot of the Yeshimon Mountains, a the Sea as far as Ain Jidy. One wrongly imagines these sb as destroyed by fire and brimstone, a thing of salt and a for thousands of years. I myself have heard the Dead which is about the size of Lac Leman, described as beir motionless as molten lead, though the surface is ruffle times into a phosphorescent foam. Birds cannot fly aero: they say, without suffocating in the air, and others report on moonlit nights an aura of the grave, the colour of absinthe, rises from its depths. None of all this have we found fc true. In fact, the Sea's waters are wonderfully clear, and b on the shore with scarcely a sound. On the high ground tc tight there are green clefts from which streams come forth. There is also to be seen a mysterious white line that is visible early in the morning. It runs the length of the Sea, and vanishes an hour or so later. No one, thus Ibrahim Hishmeh, our Arab guide, can explain it or give a reason. Ain Jidy itself is a blessèd spot with pure spring water and rich vegetation. We made our camp by some bushes on the shore where snipe stalk and the bulbul bird, brown and blue of plumage and red of beak, sings. Yesterday I thought I saw a large dark hare, and a butterfly with gold-speckled wings. In the evening, when we were sitting on the shore, Cosmo said that once the whole of the land of Zoar on the south bank was like this. Where now mere traces remained of the five overthrown cities of Gomorrha, Ruma, Sodom, Seadeh and Seboah, the oleanders once grew thirty feet high beside rivers that never ran dry, and there were acacia forests and oshac trees as in Florida. There were irrigated orchards and melon fields far and wide, and he had read a passage where Lynch, the explorer, claimed that down from the gorge of Wadi Kerek a forest torrent fell with a fearful roar that could only be compared with the Niagara Falls. - In the third night of our stay at Ain Jidy a stiff wind rose out on the Sea and stirred the heavy waters. On land it was calmer. The Arabs had long been asleep beside the horses. I was still sitting up in our bed, which was open to the heavens, in the light of the swaying lantern. Cosmo, curled up slightly, was sleeping at my side. Suddenly a quail, perhaps frightened by the storm on the Sea, took refuge in his lap and remained there, calm now, as if it were its rightful place. But at daybreak, when Cosmo stirred, it ran away quickly across the level ground, as quail do, lifted off into the air, beat its wings tremendously fast for a moment, then extended them rigid and motionless and glided by a little thicket in an utterly beautiful curve, and was gone. It was shortly before sunrise. Across the water, about twelve miles away, the blue-black ridge-line of the Moab Mountains of Araby ran level along the horizon, merely rising or dipping slightly at points, so that one might have thought the watercolourist's hand had trembled a little.

Читать дальше