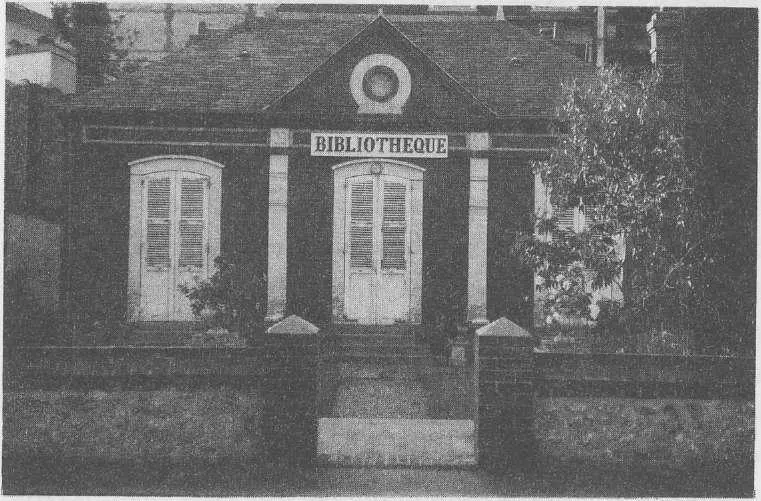

In mid September 1991, when I travelled from England to Deauville during a dreadful drought, the season was long over, and even the Festival du Cinéma Américain, with which they tried to extend the more lucrative summer months a little, had come to its end. I cannot say whether I was expecting Deauville to have something special to offer — some remnant of the past, green avenues, beach promenades, or even a stylish or scandalous clientèle; whatever my notions may have been, it was immediately apparent that the once legendary resort, like everywhere else that one visits now, regardless of the country or continent, was hopelessly run down and ruined by traffic, shops and boutiques, and the insatiable urge for destruction. The villas built in the latter half of the nineteenth century, neo-Gothic castles with turrets and battlements, Swiss chalets, and even mock-oriental residences, were almost without exception a picture of neglect and desolation. If one pauses for a while before one of these seemingly unoccupied houses, as I did a number of times on my first morning walk through the streets of Deauville, one of the closed window shutters on the parterre or bel étage or the top floor, strange to relate, will open slightly, and a hand will appear and shake out a duster, fearfully slowly, so that soon one inevitably concludes that the whole of Deauville consists of gloomy interiors where womenfolk, condemned to perpetual invisibility and eternal dusting, move soundlessly about, waiting for the moment when they can signal with their dusters to some passer-by who has happened to stop outside their prison and stand gazing up. Almost everything, in fact, was shut, both in Deauville and across the river in Trouville — the Musée Montebello, the town archives in the town hall, the library (which I had planned to look around in), and even the children's day nursery de l'enfant Jesus, established through the generosity of

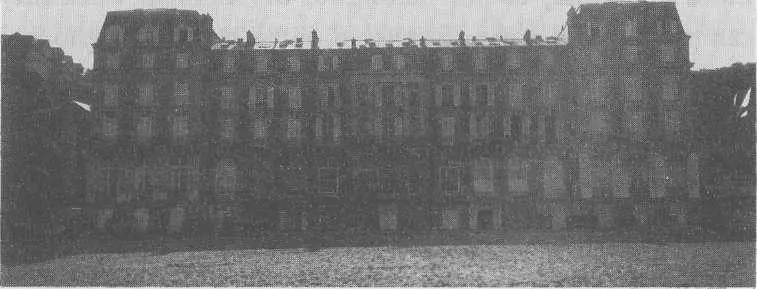

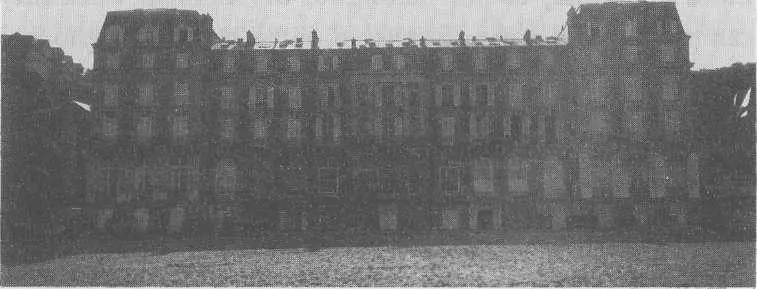

the long-deceased Madame la Baronne d'Erlanger, as I was informed by a commemorative plaque placed on the fa$ade of the building by the grateful citizens of Deauville. Nor was the Grand Hotel des Roches Noires open any more, a gigantic brick palace where American multimillionaires, English aristocrats, French high financiers and German industrialists basked in each other's company at the turn of the century. The Roches Noires, as far as I was able to

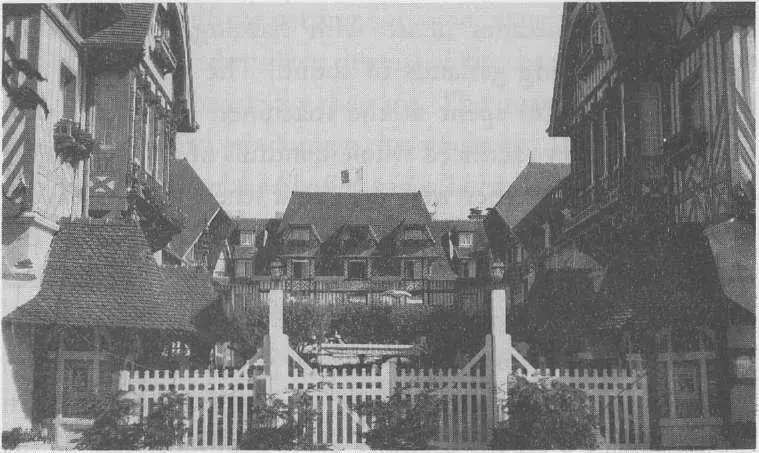

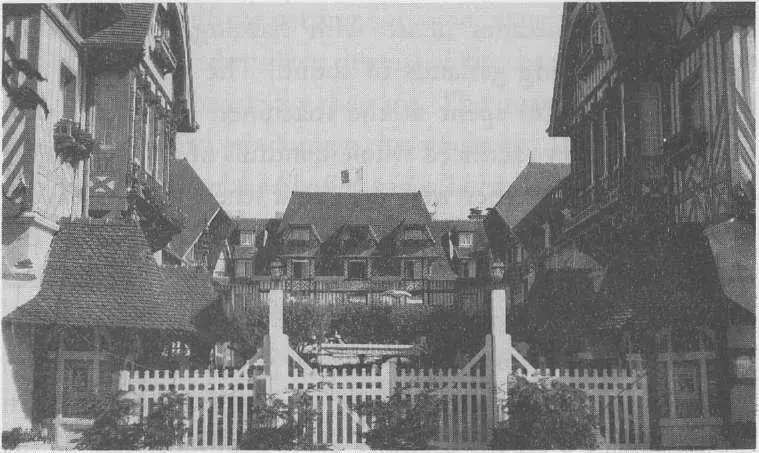

discover, had closed its doors in the Fifties or Sixties and was converted into apartments, though only those that had a sea view sold well. Now what was once the most luxurious hotel on the coast of Normandy is a monumental monstrosity half sunk in the sand. Most of the flats have long been empty, their owners having departed this life. But there are still some indestructible ladies who come every summer and haunt the immense edifice. They pull the white dustsheets off the furniture for a few weeks and at night, silent on their biers, they lie in the empty midst of it. They wander along the broad passageways, cross the huge reception rooms, climb and descend the echoing stairs, carefully placing one foot before the other, and in the early mornings they walk their ulcerous poodles and pekes on the promenade. In contrast to the Roches Noires, which is gradually falling down, the Hotel Normandy at the other end of Trouville-Deauville, completed in 1912, is still an establishment of the finest class. Built around a number of courtyards in half-timber that looks at

once outsize and miniature, it is frequented nowadays almost exclusively by the Japanese, who are steered through the minutely prescribed daily programme by the hotel staff with an exquisite but also, as I observed, ice-cold courtesy verging on the indignant. And indeed, at the Normandy one felt one was not so much in a celebrated hotel of international standing as in a gastronomic pavilion built by the French for a world fair somewhere near Osaka, and I for one should not have been surprised in the slightest if I had walked out of the Normandy to find next to it another incongruous fantasy in the Balinese or Tyrolean style. Every three days the Japanese at the Normandy were exchanged for a new contingent of their countrymen, who, as one hotel guest explained to me, were brought direct, in air-conditioned coaches, from Charles de Gaulle airport to Deauville, the third call (after Las Vegas and Atlantic City) in a global gambling tour that took them on, back to Tokyo, via Vienna, Budapest and Macao. In Deauville, every morning at ten, they would troop over to the new casino, which was built at the same time as the Normandy, where they would play the machines till lunchtime, in arcades dense with flashing, kaleidoscopic lights and tootling garlands of sound. The afternoons and evenings were also spent at the machines, to which, with stoical faces, they sacrificed whole handfuls of coins; and like children on a spree they were delighted when at last a payout tinkled forth from the box. I never saw any of them at the roulette table. As midnight approached, only a few dubious clients from the provinces would be playing there, shady lawyers, estate agents or car dealers with their mistresses, trying to out-manoeuvre Fortune, who stood before them in the person of a stocky croupier clad inappropriately in the livery of a circus attendant in the big top. The roulette table, screened off with jade-green glass paravents, was in a recently refurbished inner hall — not, in other words, where players had gambled at Deauville in former times. I knew that in those days the gaming hall was much larger. Then there had been two rows of roulette and baccarat tables as well as tables where one could bet on little horses that kept running round and round in circles. Chandeliers of Venetian glass hung from the stuccoed ceiling, and through a dozen eight-metre-high half-rounded windows one looked out onto a terrace where the most exotic of personages would be gathered, in couples or groups; and beyond the balustrade, in the light that fell from the casino, one could see the white sands and, far out, the ocean-going yachts and small steamers, lit up and riding at anchor, beaming their Aldis lamps into the night sky, and little boats moving to and fro like slow glow-worms between them and the coast. When I first set foot in the casino at Deauville, the old gaming hall was filled with the last glimmer of evening light. Tables had been laid for a good hundred people, for a wedding banquet or some anniversary celebration. The rays of the setting sun were caught by the glasses and glinted on the silver drums of the band that was just beginning to rehearse for their gig. The instrumentalists were curly-haired and no longer the youngest. The songs they played dated from the Sixties, songs I heard countless times in the Union bar in Manchester. It is the evening of the day. The vocalist, a blonde girl with a voice still distinctly child-like, breathed passionately into the microphone, which she held up close to her lips with both hands. She was singing in English, though with a pronounced French accent. It is the evening of the day, I sit and watch the children play. At times, when she could not remember the proper words, her singing would become an ethereal hum. I sat down in one of the white lacquer chairs. The music filled the whole room. Pink puffy clouds right up to the golden arabesques of the ceiling stucco. "A whiter shade of pale."

Читать дальше