It was (so supposedly once he said) as if one was sinking into sand. This was probably the reason, she said, that sand possessed such significance in all of Flaubert's works. Sand conquered all. Time and again, said Janine, vast dust clouds drifted through Flaubert's dreams by day and by night, raised over the arid plains of the African continent and moving north across the Mediterranean and the Iberian peninsula till sooner or later they settled like ash from a fire on the Tuileries gardens, a suburb of Rouen or a country town in Normandy, penetrating into the tiniest crevices. In a grain of sand in the hem of Emma Bovary's winter gown, said Janine, Flaubert saw the whole of the Sahara. For him, every speck of dust weighed as heavy as the Atlas mountains. Many a time, at the end of a working day. Janine would talk to me about Flaubert's view of the world, in her office where there were such quantities of lecture notes, letters and other documents lying around that it was like standing amidst a flood of paper. On the desk, which was both the origin and the focal point of this amazing profusion of paper, a virtual paper landscape had come into being in the course of time, with mountains and valleys. Like a glacier when it reaches the sea, it had broken off at the edges and established new deposits all around on the floor, which in turn were advancing imperceptibly towards the centre of the room. Years ago, Janine had been obliged by the ever-increasing masses of paper on her desk to bring further tables into use, and these tables, where similar processes of accretion had subsequently taken place, represented later epochs, so to speak, in the evolution of Janine's paper universe. The carpet, too, had long since vanished beneath several inches of paper; indeed, the paper had begun climbing from the floor, on which, year after year, it had settled, and was now up the walls as high as the top of the door frame, page upon page of memoranda and notes pinned up in multiple layers, all of them by just one corner. Wherever it was possible there were piles of papers on the books on her shelves as well. It once occurred to me that at dusk, when all this paper seemed to gather into itself the pallor of the fading light, it was like the snow in the fields, long ago, beneath the ink-black sky. In the end Janine was reduced to working from an easy chair drawn more or less into the middle of her room where, if one passed her door, which was always ajar, she could be seen bent almost double scribbling on a pad on her knees or sometimes just lost in thought. Once when I remarked that sitting there amidst her papers she resembled the angel in Dürer's

Melancholia , steadfast among the instruments of destruction, her response was that the apparent chaos surrounding her represented in reality a perfect kind of order, or an order which at least tended towards perfection. And the fact was that whatever she might be looking for amongst her papers or her books, or in her head, she was generally able to find right away. It was Janine who referred me to the surgeon Anthony Batty Shaw, whom she knew from the Oxford Society, when after my discharge from hospital I began my enquiries about Thomas Browne, who had practised as a doctor in Norwich in the seventeenth century and had left a number of writings that defy all comparison. An entry in the 1911 edition of the

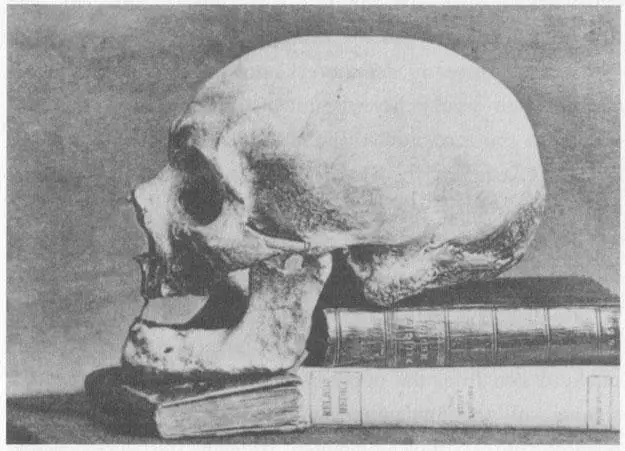

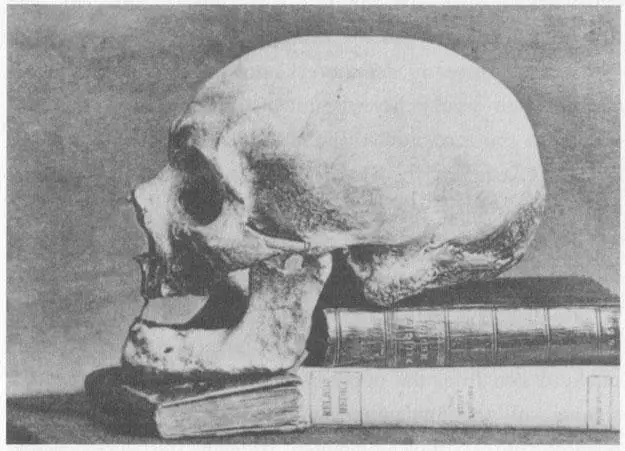

Encyclopaedia Britannica had told me that Browne's skull was kept in the museum of the Norfolk & Norwich Hospital. Unequivocal though this claim appeared, my attempts to locate the skull in the very place where until recently I had been a patient met with no success, for none of the ladies and gentlemen of the present administrative staff at the hospital was aware that any such museum existed. Not only did they stare at me in utter incomprehension when I voiced my strange request, but I even had the impression that some of those I asked thought of me as an eccentric crank. Yet it is well known that in the period when public health and hygiene were being reformed and hospitals established, many of these institutions kept museums, or rather chambers of horrors, in which prematurely born, deformed or hydrocephalic foetuses, were preserved in jars of formaldehyde, for medical purposes, and occasionally exhibited to the public. The question was where the things had got to. The local history section of the main library, which has since been destroyed by fire, was unable to give me any information concerning the Norfolk & Norwich Hospital and the whereabouts of Browne's skull. It was not until I made contact with Anthony Batty Shaw, through Janine, that I obtained the information I was after. Thomas Browne, so Batty Shaw wrote in an article he sent me which he had just published in the

Journal of Medical Biography , died in 1682 on his seventy-seventh birthday and was buried in the parish church of St Peter Mancroft in Norwich. There his mortal remains lay undisturbed until 1840, when the coffin was damaged during preparations for another burial in the chancel, and its contents partially exposed. As a result, Browne's skull and a lock of his hair passed into the possession of one Dr Lubbock, a parish councillor, who in turn left the relics in his will to the hospital museum, where they were put on display amidst various anatomical curiosities until 1921 under a bell jar. It was not until then that St Peter Mancroft's repeated request for the return of Browne's skull was acceded to, and, almost a quarter of a millenium after the first burial, a second interment was performed with all due ceremony. Curiously enough, Browne himself, in his famous part-archaeological and part-metaphysical treatise,

Urn Burial , offers the most fitting commentary on the subsequent odyssey of his own skull when he writes that to be gnaw'd out of our graves is a tragical abomination. But, he adds, who is to know the fate of his bones, or how often he is to be buried?

Thomas Browne was born in London on the 19th of October 1605, the son of a silk merchant. Little is known of his childhood, and the accounts of his life following completion of his master's degree at Oxford tell us scarcely anything about the nature of his later medical studies. All we know for certain is that from his twenty-fifth to his twenty-eighth year he attended the universities of Montpellier, Padua and Vienna, then outstanding in the Hippocratic sciences, and that just before returning to England, received a doctorate in medicine from Leiden. In January 1632, while Browne was in Holland, and thus at a time when he was engaging more profoundly with the mysteries of the human body than ever before, the dissection of a corpse was undertaken in public at the Waaggebouw in Amsterdam — the body being that of Adriaan Adriaanszoon alias Aris Kindt, a petty thief of that city who had been hanged for his misdemeanours an hour or so earlier. Although we have no definite evidence for this, it is probable that Browne would have heard of the dissection and was present at the extraordinary event, which Rembrandt depicted in his painting of the Guild of Surgeons, for the anatomy lessons given every year in the depth of winter by Dr Nicolaas Tulp were not only of the greatest interest to a student of medicine but constituted in addition a significant date in the agenda of a society that saw itself as emerging from the darkness into the light. The spectacle, presented before a paying public drawn from the upper classes, was no doubt a demonstration of the undaunted investigative zeal in the new sciences; but it also represented (though this surely would have been refuted) the archaic ritual of dismembering a corpse, of harrowing the flesh of the delinquent even beyond death, a procedure then still part of the ordained punishment. That the anatomy lesson in Amsterdam was about more than a thorough knowledge of the inner organs of the human body is suggested by Rembrandt's representation of the ceremonial nature of the dissection — the surgeons are in their finest attire, and Dr Tulp is wearing a hat on his head — as well as by the fact that afterwards there was a formal, and in a sense symbolic banquet. If we stand today before the large canvas of Rembrandt's The Anatomy Lesson in the Mauritshuis we are standing precisely where those who were present at the dissection in the Waaggebouw stood, and we believe that we see what they saw then: in the foreground, the greenish, prone body of Aris Kindt, his neck broken and his chest risen terribly in rigor mortis. And yet it is debatable whether anyone ever really saw that body, since the art of anatomy, then in its infancy, was not least a way of making the reprobate body invisible. It is somehow odd that Dr Tulp's colleagues are not looking at Kindt's body, that their gaze is directed just past it to focus on the open anatomical atlas in which the appalling physical facts are reduced to a diagram, a schematic plan of the human being, such as envisaged by the enthusiastic amateur anatomist René Descartes, who was also, so it is said, present that January morning in the Waaggebouw. In his philosophical investigations, which form one of the principal chapters of the history of subjection, Descartes teaches that one should disregard the flesh, which is beyond our comprehension, and attend to the machine within, to what can fully be understood, be made wholly useful for work, and, in the event of any fault, either repaired or discarded.

Читать дальше