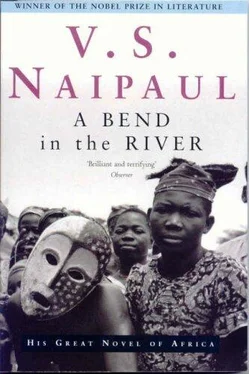

V. Naipaul - A bend in the river

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «V. Naipaul - A bend in the river» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1989, ISBN: 1989, Издательство: Vintage, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A bend in the river

- Автор:

- Издательство:Vintage

- Жанр:

- Год:1989

- ISBN:978-0679722021

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A bend in the river: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A bend in the river»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

) V.S. Naipaul takes us deeply into the life of one man—an Indian who, uprooted by the bloody tides of Third World history, has come to live in an isolated town at the bend of a great river in a newly independent African nation. Naipaul gives us the most convincing and disturbing vision yet of what happens in a place caught between the dangerously alluring modern world and its own tenacious past and traditions.

A bend in the river — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A bend in the river», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

A radio was on in the flat. It was unusually loud, and as I went up the external staircase I had the impression that Metty was listening to a football match commentary from the capital. An echoing voice was varying its pace and pitch, and there was the roar of a crowd. Metty's door was open and he was sitting in pants and undershirt on the edge of his cot. The light from the central hanging bulb in his room was yellow and dim; the radio was deafening. Looking up at me, then looking down again, concentrating, Metty said, "The President." That was clear, now that I had begun to follow the words. It explained why Metty felt he didn't have to turn the radio down. The speech had been announced; I had forgotten. The President was talking in the African language that most people who lived along the river understood. At one time the President's speeches were in French. But in this speech the only French words were _citoyens__ and _citoyennes__, and they were used again and again, for musical effect, now run together into a rippling phrase, now called out separately, every syllable spaced, to create the effect of a solemn drumbeat. The African language the President had chosen for his speeches was a mixed and simple language, and he simplified it further, making it the language of the drinking booth and the street brawl, converting himself, while he spoke, this man who kept everybody dangling and imitated the etiquette of royalty and the graces of de Gaulle, into the lowest of the low. And that was the attraction of the African language in the President's mouth. That regal and musical use of the lowest language and the coarsest expressions was what was holding Metty. Metty was absorbed. His eyes, below the yellow highlights on his forehead, were steady, small, intent. His lips were compressed and in his concentration he kept working them. When the coarse expressions or the obscenities occurred, and the crowd roared, Metty laughed without opening his mouth. The speech, so far, was like many others the President had made. The themes were not new: sacrifice and the bright future; the dignity of the woman of Africa; the need to strengthen the revolution, unpopular though it was with those black men in the towns who dreamed of waking up one day as white men; the need for Africans to be African, to go back without shame to their democratic and socialist ways, to rediscover the virtues of the diet and medicines of their grandfathers and not to go running like children after things in imported tins and bottles; the need for vigilance, work and, above all, discipline. This was how, while appearing just to restate old principles, the President also acknowledged and ridiculed new criticism, whether it was of the madonna cult or of the shortage of food and medicines. He always acknowledged criticism, and he often anticipated it. He made everything fit; he could suggest he knew everything. He could make it appear that everything that was happening in the country, good or bad or ordinary, was part of a bigger plan. People liked to listen to the President's speeches because so much was familiar; like Metty now, they waited for the old jokes. But every speech was also a new performance, with its own dramatic devices; and every speech had a purpose. This speech was of particular concern to our town and region. That was what the President said, and it became one of the dramatic devices of the later part of the speech: he broke off again and again to say that he had something to say to the people of our town and region, but we had to wait for it. The crowd in the capital, recognizing the device as a device, a new piece of style, began to roar when they saw it coming. We in the region liked our beer, the President said. He liked it better; he could outdrink anyone of us any day. But we mustn't get pissed too soon; he had something to say to us. And it was known that the statement the President was going to make was about our Youth Guard. For a fortnight or more we had been waiting for this statement; for a fortnight he had kept the whole town dangling. The Youth Guard had never recovered their prestige after the failure of the book march. Their children's marches on Saturday afternoons had grown raggeder and thinner, and the officers had found that they had no means of compelling children to take part. They had kept on with the Morals Patrol. But the nighttime crowds were now more hostile; and one evening an officer of the Guard had been killed. It had begun as a squabble with some pavement sleepers who had barred off a stretch of pavement in a semipermanent way with concrete blocks looted from a building site. And it could easily have ended as a shouting match, no more. But the officer had stumbled and fallen. By that fall, that momentary appearance of helplessness, he had invited the first blow with one of the concrete blocks; and the sight of blood then had encouraged a sudden, frenzied act of murder by dozens of small hands. No one had been arrested. The police were nervous; the Youth Guard were nervous; the people of the streets were nervous. There was talk a few days later that the army was going to be sent in to beat up some of the shanty towns. That had caused a little scuttle back to the villages; the dugouts had been busy. But nothing had happened. Everyone had been waiting to see what the President would do. But for more than a fortnight the President had said and done nothing. And what the President said now was staggering. The Youth Guard in our region was to be disbanded. They had forgotten their duty to the people; they had broken faith with him, the President; they had talked too much. The officers would lose their stipend; there would be no government jobs for any of them; they would be banished from the town and sent back to the bush, to do constructive work there. In the bush they would learn the wisdom of the monkey. "_Citoyens-citoyennes__, monkey smart. Monkey smart like shit. Monkey can talk. You didn't know that? Well, I tell you now. Monkey can talk, but he keep it quiet. Monkey know that if he talk in front of man, man going to catch him and beat him and make him work. Make him carry load in hot sun. Make him paddle boat. _Citoyens! Citoyennes__! We will teach these people to be like monkey. We will send them to the bush and let them work their arse off."

CHAPTER 14

It was the Big Man's way. He chose his time, and what looked like a challenge to his authority served in the end to underline his authority. He showed himself again as the friend of the people, the _petit peuple__, as he liked to call them, and he punished their oppressors. But the Big Man hadn't visited our town. Perhaps, as Raymond said, the reports he had been receiving were inaccurate or incomplete. And this time something went wrong. We had all thought of the Youth Guard as a menace, and everybody was happy to see them go. But it was after the disbanding of the Youth Guard that things began to get bad in our town. The police and other officials became difficult. They took to tormenting Metty whenever he took the car out, even on the short run to the customs. He was stopped again and again, sometimes by people he knew, sometimes by people who had stopped him before, and the car's documents were checked, and his own papers. Sometimes he had to leave the car where it was and walk back to the shop to get some certificate or paper he didn't have. And it didn't help if he had all the papers. Once, for no reason at all, he was taken to police headquarters, fingerprinted and--in the company of other dispirited people who had been picked up--made to spend a whole afternoon with blackened hands in a room with backless wooden benches, a broken concrete floor and blue distempered walls grimy and shining from the heads and shoulders that had rubbed against them. The room, from which I rescued him late in the afternoon, having spent a lot of time tracking him down, was in a rough concrete and corrugated-iron shed at the back of the main colonial building. The floor was just a few inches above the ground; the door was open, and chickens were scratching about in the bare yard. But rough and homely and full of afternoon light as it was, the room hinted at the jail. The one table and chair belonged to the officer in charge, and these scrappy pieces of furniture emphasized the deprivation of everybody else. The officer was sweating under the arms in his over-starched uniform, and he was writing very slowly in a ledger, shaping one letter at a time, apparently entering details from the blotched fingerprint sheets. He had a revolver. There was a photograph of the President showing his chief's stick; and above it on the blue wall, high up, where the uneven surface was dusty rather than grimy, was painted _Discipline Avant Tout__--"Discipline Above All." I didn't like that room, and I thought it would be better after that for Metty not to use the car and for me to be my own customs clerk and broker. But then the officials turned their attention to me. They dug up old customs declaration forms, things that had been sealed and settled in the standard way long ago, and brought them to the shop and waved them in my face like unredeemed IOUs. They said they were under pressure from their superiors and wanted to go through certain details with me again. At first they were shy, like wicked schoolboys; then they were conspiratorial, like friends wanting to do me a secret good turn; then they were aggressive, like wicked officials. Others wanted to check my stock against my customs declarations and my sales receipts; others said they wanted to investigate my prices. It was harassment, and the purpose was money, and money fast, before everything changed. These men had sniffed some change coming; in the disbanding of the Youth Guard they had seen signs of the President's weakness rather than strength. And in this situation there was no one I could appeal to. Every official was willing, for a consideration, to give assurances about his own conduct. But no official was high enough or secure enough to guarantee the conduct of any other official. Everything in the town was as it had been--the army was in its barracks, the photographs of the President were everywhere, the steamer came up regularly from the capital. But men had lost or rejected the idea of an overseeing authority, and everything was again as fluid as it had been at the beginning. Only this time, after all the years of peace and goods in all the shops, everyone was greedier. What was happening to me was happening to every other foreign businessman. Even Noimon, if he had still been around, would have suffered. Mahesh was gloomier than ever. He said, "I always say: You can hire them, but you can't buy them." It was one of his sayings; it meant that stable relationships were not possible here, that there could only be day-to-day contracts between men, that in a crisis peace was something you had to buy afresh every day. His advice was to stick it out. And there was nothing else we could do. My own feeling--my secret comfort during this time--was that the officials had misread the situation and that their frenzy was self-induced. Like Raymond, I had grown to believe in the power wisdom of the President, and was confident he would do something to reassert his authority. So I prevaricated and didn't pay, seeing no end to paying if I should start. But the patience of the officials was greater than mine. It is no exaggeration to say that not a day passed now without some official calling. I began to wait for their calls. It was bad for my nerves. In the middle of the afternoon, if no one had yet called, I could find myself sweating. I grew to hate, and fear, those smiling _malin__ faces pushed up close to mine in mock familiarity and helpfulness. And then the pressure eased. Not because the President acted, as I had been hoping. But because violence had come to our town. Not the evening drama of street brawls and murders, but a steady, nightly assault in different areas on policemen and police stations and officials and official buildings. It was this, no doubt, that the officials had seen coming, and I hadn't. This was what had made them greedy to grab as much as they could while they could. One night the statue of the African madonna and child in the Domain was knocked off its pedestal and smashed, as the colonial statues had once been smashed, and the monument outside the dock gates. After this the officials began to make themselves scarce. They stayed away from the shop; they had too many other things to do. And though I couldn't say things were better, yet the violence came as a relief and for a while, to me as well as to the people I saw in the streets and squares, was even exhilarating, the way a big fire or a storm can be exhilarating. In our overgrown, overpopulated, unregulated town we had had any number of violent outbursts. There had been riots about water, and on many occasions in the shanty towns there had been riots when someone had been killed by a car. In what was happening now there was still that element of popular frenzy; but it was also clear that it was more organized, or that at least it had some deeper principle. Some prophecy, perhaps, had been making the rounds of the _cites__ and shanty towns and had found confirmation in the dreams of various people. It was the kind of thing the officials would have got wind of. One morning, when he brought me coffee, Metty, looking serious, gave me a piece of newsprint, folded small and carefully, and dirty along the outer creases. It was a printed leaflet and had obviously been folded and unfolded many times. It was headlined "The Ancestors Shriek," and was issued by something called the Liberation Army.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A bend in the river»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A bend in the river» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A bend in the river» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.