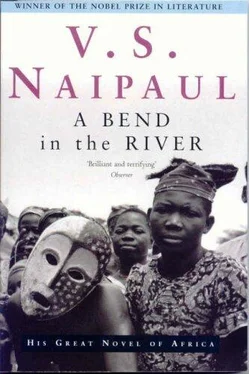

V. Naipaul - A bend in the river

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «V. Naipaul - A bend in the river» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1989, ISBN: 1989, Издательство: Vintage, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A bend in the river

- Автор:

- Издательство:Vintage

- Жанр:

- Год:1989

- ISBN:978-0679722021

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A bend in the river: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A bend in the river»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

) V.S. Naipaul takes us deeply into the life of one man—an Indian who, uprooted by the bloody tides of Third World history, has come to live in an isolated town at the bend of a great river in a newly independent African nation. Naipaul gives us the most convincing and disturbing vision yet of what happens in a place caught between the dangerously alluring modern world and its own tenacious past and traditions.

A bend in the river — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A bend in the river», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

You heard that kind of property talk everywhere now. Everyone was totting up how much he had gained with the boom, how much he was worth. People learned to speak huge figures calmly. There had been a boom before, just at the end of the colonial period, and the ruined suburb near the rapids was what it had left behind. Nazruddin had told a story about that. He had gone out there one Sunday morning, had thought that the place was bush rather than real estate, and had decided to sell. Lucky for him then; but now that dead suburb was being rehabilitated. That development or redevelopment had become the most important feature of our boom. And it had caused the big recent rise in property values in the town. The bush near the rapids was being cleared. The ruins which had seemed permanent were being levelled by bulldozers; new avenues were being laid out. It was the Big Man's doing. The government had taken over all that area and decreed it the Domain of the State, and the Big Man was building what looked like a little town there. It was happening very fast. The copper money was pouring in, pushing up prices in our town. The deep, earth-shaking burr of bulldozers competed with the sound of the rapids. Every steamer brought up European builders and artisans, every airplane. The van der Weyden seldom had rooms to spare. Everything the President did had a reason. As a ruler in what was potentially hostile territory, he was creating an area where he and his flag were supreme. As an African, he was building a new town on the site of what had been a rich European suburb--but what he was building was meant to be grander. In the town the only "designed" modern building was the van der Weyden; and to us the larger buildings of the Domain were startling--concrete louvres, pierced concrete blocks of great size, tinted glass. The smaller buildings--houses and bungalows--were more like what we were used to. But even they were on the large side and, with air conditioners sticking out in many places like building blocks that had slipped, looked extravagant. No one was sure, even after some of the houses were furnished, what the Domain was to be used for. There were stories of a great new model farm and agricultural college; a conference hall to serve the continent; holiday houses for loyal citizens. From the President himself there came no statement. We watched and wondered while the buildings were run up. And then we began to understand that what the President was attempting was so stupendous in his own eyes that even he would not have wanted to proclaim it. He was creating modern Africa. He was creating a miracle that would astound the rest of the world. He was by-passing real Africa, the difficult Africa of bush and villages, and creating something that would match anything that existed in other countries. Photographs of this State Domain--and of others like it in other parts of the country--began to appear in those magazines about Africa that were published in Europe but subsidized by governments like ours. In these photographs the message of the Domain was simple. Under the rule of our new President the miracle had occurred: Africans had become modern men who built in concrete and glass and sat in cushioned chairs covered in imitation velvet. It was like a curious fulfilment of Father Huismans's prophecy about the retreat of African Africa, and the success of the European graft. Visitors were encouraged, from the _cites__ and shanty towns, from the surrounding villages. On Sundays there were buses and army trucks to take people there, and soldiers acted as guides, taking people along one-way paths marked with directional arrows, showing the people who had recently wished to destroy the town what their President had done for Africa. Such shoddy buildings, after you got used to the shapes; such flashy furniture--Noimon was making a fortune with his furniture shop. All around, the life of dugout and creek and village continued; in the bars in the town the foreign builders and artisans drank and made easy jokes about the country. It was painful and it was sad. The President had wished to show us a new Africa. And I saw Africa in a way I had never seen it before, saw the defeats and humiliations which until then I had regarded as just a fact of life. And I felt like that--full of tenderness for the Big Man, for the ragged villagers walking around the Domain, and the soldiers showing them the shabby sights--until some soldier played the fool with me or some official at the customs was difficult, and then I fell into the old way of feeling, the easier attitudes of the foreigners in the bars. Old Africa, which seemed to absorb everything, was simple; this place kept you tense. What a strain it was, picking your way through stupidity and aggressiveness and pride and hurt! But what was the Domain to be used for? The buildings gave pride, or were meant to; they satisfied some personal need of the President's. Was that all they were for? But they had consumed millions. The farm didn't materialize. The Chinese or the Taiwanese didn't turn up to till the land of the new model African farm; the six tractors that some foreign government had given remained in a neat line in the open and rusted, and the grass grew high about them. The big swimming pool near the building that was said to be a conference hall developed leaks and remained empty, with a wide-meshed rope net at the top. The Domain had been built fast, and in the sun and the rain decay also came fast. After the first rainy season many of the young trees that had been planted beside the wide main avenue died, their roots waterlogged and rotted. But for the President in the capital the Domain remained a living thing. Statues were added, and lamp standards. The Sunday visits went on; the photographs continued to appear in the subsidized magazines that specialized in Africa. And then at last a use was found for the buildings. The Domain became a university city and a research centre. The conference-hall building was turned into a polytechnic for people of the region, and other buildings were turned into dormitories and staff quarters. Lecturers and professors began to come from the capital, and soon from other countries; a parallel life developed there, of which we in the town knew little. And it was to the polytechnic there--on the site of the dead European suburb that to me, when I first came, had suggested the ruins of a civilization that had come and gone--that Ferdinand was sent on a government scholarship, when he had finished at the lyc�

The Domain was some miles away from the town. There was a bus service, but it was irregular. I hadn't been seeing much of Ferdinand, and now I saw even less of him. Metty lost a friend. That move of Ferdinand's finally made the difference between the two men clear, and I thought that Metty suffered. My own feelings were more complicated. I saw a disordered future for the country. No one was going to be secure here; no man of the country was to be envied. Yet I couldn't help thinking how lucky Ferdinand was, how easy it had been made for him. You took a boy out of the bush and you taught him to read and write; you levelled the bush and built a polytechnic and you sent him there. It seemed as easy as that, if you came late to the world and found ready-made those things that other countries and peoples had taken so long to arrive at--writing, printing, universities, books, knowledge. The rest of us had to take things in stages. I thought of my own family, Nazruddin, myself--we were so clogged by what the centuries had deposited in our minds and hearts. Ferdinand, starting from nothing, had with one step made himself free, and was ready to race ahead of us. The Domain, with its shoddy grandeur, was a hoax. Neither the President who had called it into being nor the foreigners who had made a fortune building it had faith in what they were creating. But had there been greater faith before? _Miscerique probat populos et foedera jungi__: Father Huismans had explained the arrogance of that motto. He had believed in its truth. But how many of the builders of the earlier city would have agreed with him? Yet that earlier hoax had helped to make men of the country in a certain way; and men would also be made by this new hoax. Ferdinand took the polytechnic seriously; it was going to lead him to an administrative cadetship and eventually to a position of authority. To him the Domain was fine, as it should be. He was as glamorous to himself at the polytechnic as he had been at the lyc� It was absurd to be jealous of Ferdinand, who still after all went home to the bush. But I wasn't jealous of him only because I felt that he was about to race ahead of me in knowledge and enter realms I would never enter. I was jealous more of that idea he had always had of his own importance, his own glamour. We lived on the same patch of earth; we looked at the same views. Yet to him the world was new and getting newer. For me that same world was drab, without possibilities. I grew to detest the physical feel of the place. My flat remained as it had always been. I had changed nothing there, because I lived with the idea that at a moment's notice I had to consider it all as lost--the bedroom with the white-painted window panes and the big bed with the foam mattress, the roughly made cupboards with my smelly clothes and shoes, the kitchen with its smell of kerosene and frying oil and rust and dirt and cockroaches, the empty white studio-sitting room. Always there, never really mine, reminding me now only of the passing of time. I detested the imported ornamental trees, the trees of my childhood, so unnatural here, with the red dust of the streets that turned to mud in rain, the overcast sky that meant only more heat, the clear sky that meant a sun that hurt, the rain that seldom cooled and made for a general clamminess, the brown river with the lilac-coloured flowers on rubbery green vines that floated on and on, night and day. Ferdinand had moved only a few miles away. And I, so recently his senior, felt jealous and deserted.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A bend in the river»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A bend in the river» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A bend in the river» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.