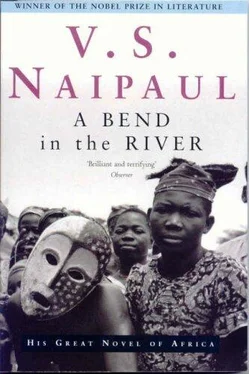

V. Naipaul - A bend in the river

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «V. Naipaul - A bend in the river» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1989, ISBN: 1989, Издательство: Vintage, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A bend in the river

- Автор:

- Издательство:Vintage

- Жанр:

- Год:1989

- ISBN:978-0679722021

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A bend in the river: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A bend in the river»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

) V.S. Naipaul takes us deeply into the life of one man—an Indian who, uprooted by the bloody tides of Third World history, has come to live in an isolated town at the bend of a great river in a newly independent African nation. Naipaul gives us the most convincing and disturbing vision yet of what happens in a place caught between the dangerously alluring modern world and its own tenacious past and traditions.

A bend in the river — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A bend in the river», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

What Ferdinand had said about Father Huismans's collection, other people began to say. While he lived, Father Huismans, collecting the things of Africa, had been thought a friend of Africa. But now that changed. It was felt that the collection was an affront to African religion, and no one at the lyc�took it over. Perhaps there was no one there with the knowledge and the eye that were required. Visitors were sometimes shown the collection. The wooden carvings remained as they were; but in the un-ventilated gun room the masks began to deteriorate and the smell became more unpleasant. The masks themselves, crumbling on the slatted shelves, seemed to lose the religious power Father Huismans had taught me to see in them; without him, they simply became extravagant objects. In the long peace that now settled on the town, we began to receive visitors from a dozen countries, teachers, students, helpers in this and that, people who behaved like discoverers of Africa, were happy with everything they found, and looked down quite a bit on foreigners like ourselves who had been living there. The collection began to be pillaged. Who more African than the young American who appeared among us, who more ready to put on African clothes and dance African dances? He left suddenly by the steamer one day; and it was discovered afterwards that the bulk of the collection in the gun room had been crated and shipped back with his belongings to the United States, no doubt to be the nucleus of the gallery of primitive art he often spoke of starting. The richest products of the forest.

TWO. THE NEW DOMAIN

CHAPTER 6

If you look at a column of ants on the march you will see that there are some who are stragglers or have lost their way. The column has no time for them; it goes on. Sometimes the stragglers die. But even this has no effect on the column. There is a little disturbance around the corpse, which is eventually carried off--and then it appears so light. And all the time the great busyness continues, and that apparent sociability, that rite of meeting and greeting which ants travelling in opposite directions, to and from their nest, perform without fail. So it was after the death of Father Huismans. In the old days his death would have caused anger, and people would have wanted to go out to look for his killers. But now we who remained--outsiders, but neither settlers nor visitors, just people with nowhere better to go--put our heads down and got on with our business. The only message of his death was that we had to be careful ourselves and remember where we were. And oddly enough, by acting as we did, by putting our heads down and getting on with our work, we helped to bring about what he had prophesied for our town. He had said that our town would suffer setbacks but that they would be temporary. After each setback, the civilization of Europe would become a little more secure at the bend in the river; the town would always start up again, and would grow a little more each time. In the peace that we now had, the town wasn't only reestablished; it grew. And the rebellion and Father Huismans's death receded fast. We didn't have Father Huismans's big views. Some of us had our own clear ideas about Africans and their future. But it occurred to me that we did really share his faith in the future. Unless we believed that change was coming to our part of Africa, we couldn't have done our business. There would have been no point. And--in spite of appearances--we also had the attitude to ourselves that he had to himself. He saw himself as part of a great historical process; he would have seen his own death as unimportant, hardly a disturbance. We felt like that too, but from a different angle. We were simple men with civilizations but without other homes. Whenever we were allowed to, we did the complicated things we had to do, like the ants. We had the occasional comfort of reward, but in good times or bad we lived with the knowledge that we were expendable, that our labour might at any moment go to waste, that we ourselves might be smashed up; and that others would replace us. To us that was the painful part, that others would come at the better time. But we were like the ants; we kept on. People in our position move rapidly from depression to optimism and back down again. Now we were in a period of boom. We felt the new ruling intelligence--and energy--from the capital; there was a lot of copper money around; and these two things--order and money--were enough to give us confidence. A little of that went a long way with us. It released our energy; and energy, rather than quickness or great capital, was what we possessed. All kinds of projects were started. Various government departments came to life again; and the town at last became a place that could be made to work. We already had the steamer service; now the airfield was recommissioned and extended, to take the jets from the capital (and to fly in soldiers). The _cit�_ filled up, and new ones were built, though nothing that was done could cope with the movement of people from the villages; we never lost the squatters and campers in our central streets and squares. But there were buses now, and many more taxis. We even began to get a new telephone system. It was far too elaborate for our needs, but it was what the Big Man in the capital wanted for us. The growth of the population could be gauged by the growth of the rubbish heaps in the _cit�_. They didn't burn their rubbish in oil drums, as we did; they just threw it out on the broken streets--that sifted, ashy African rubbish. Those mounds of rubbish, though constantly flattened by rain, grew month by month into increasingly solid little hills, and the hills literally became as high as the box-like concrete houses of the _cit�_. Nobody wanted to move that rubbish. But the taxis stank of disinfectant; the officials of our health department were fierce about taxis. And for this reason. In the colonial days public vehicles had by law to be disinfected once a year by the health department. The disin-fectors were entitled to a personal fee. That custom had been remembered. Any number of people wanted to be disinfectors; and now taxis and trucks weren't disinfected just once a year; they were disinfected whenever they were caught. The fee had to be paid each time; and disinfectors in their official jeeps played hide and seek with taxis and trucks among the hills of rubbish. The red dirt roads of our town, neglected for years, had quickly become corrugated with the new traffic we had; and these disinfectant chases were in a curious kind of slow motion, with the vehicles of hunters and hunted pitching up and down the corrugations like launches in a heavy sea. All the people--like the health officials--who performed services for ready money were energetic, or could be made so: the customs people, the police, and even the army. The administration, however hollow, was fuller; there were people you could appeal to. You could get things done, if you knew how to go about it. And the town at the bend in the river became again what Father Huismans had said it had always been, long before the peoples of the Indian Ocean or Europe came to it. It became the trading centre for the region, which was vast. _Marchands__ came in now from very far away, making journeys much more difficult than Zabeth's; some of those journeys took a week. The steamer didn't go beyond our town; above the rapids there were only dugouts (some with outboard motors) and a few launches. Our town became a goods depot, and I acquired a number of agencies (reassuming some that Ferdinand had had) for things that until then I had more or less been selling retail. There was money in agencies. The simpler the product, the simpler and better the business. It was a different kind of business from the retail trade. Electric batteries, for instance--I bought and sold quantities long before they arrived; I didn't have to handle them physically or even see them. It was like dealing in words alone, ideas on paper; it was like a form of play--until one day you were notified that the batteries had arrived, and you went to the customs warehouse and saw that they existed, that workmen somewhere had actually made the things. Such useful things, such necessary things--they would have been acceptable in a plain brown-paper casing; but the people who had made them had gone to the extra trouble of giving them pretty labels, with tempting slogans. Trade, goods! What a mystery! We couldn't make the things we dealt in; we hardly understood their principles. Money alone had brought these magical things to us deep in the bush, and we dealt in them so casually! Salesmen from the capital, Europeans most of them, preferring to fly up now rather than spend seven days on the steamer coming up and five going down, began to stay at the van der Weyden, and they gave a little variety to our social life. In the Hellenic Club, in the bars, they brought at last that touch of Europe and the big city--the atmosphere in which, from his stories, I had imagined Nazruddin living here.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A bend in the river»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A bend in the river» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A bend in the river» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.