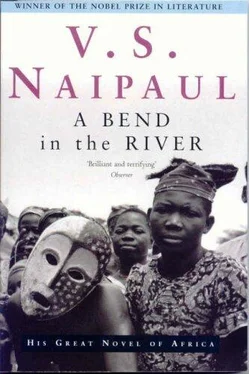

V. Naipaul - A bend in the river

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «V. Naipaul - A bend in the river» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1989, ISBN: 1989, Издательство: Vintage, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A bend in the river

- Автор:

- Издательство:Vintage

- Жанр:

- Год:1989

- ISBN:978-0679722021

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A bend in the river: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A bend in the river»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

) V.S. Naipaul takes us deeply into the life of one man—an Indian who, uprooted by the bloody tides of Third World history, has come to live in an isolated town at the bend of a great river in a newly independent African nation. Naipaul gives us the most convincing and disturbing vision yet of what happens in a place caught between the dangerously alluring modern world and its own tenacious past and traditions.

A bend in the river — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A bend in the river», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

CHAPTER 8

Indar said, "We are going to a party after dinner. It's being given by Yvette. Do you know her? Her husband, Raymond, keeps a low profile, but he runs the whole show here. The President, or the Big Man, as you call him, sent him down here to keep an eye on things. He's the Big Man's white man. In all these places there's someone like that. Raymond's a historian. They say the President reads everything he writes. That's the story anyway. Raymond knows more about the country than anyone on earth." I had never heard of Raymond. The President I had seen only in photographs--first in army uniform, then in the stylish short-sleeved jacket and cravat, and then with his leopard-skin chief's cap and his carved stick, emblem of his chieftaincy--and it had never occurred to me that he might be a reader. What Indar told me brought the President closer. At the same time it showed me how far away I, and people like me, were from the seat of power. Considering myself from that distance, I saw how small and vulnerable we were; and it didn't seem quite real that, dressed as I was, I should be strolling across the Domain after dinner to meet people in direct touch with the great. It was strange, but I no longer felt oppressed by the country, the forest and the waters and the remote peoples: I felt myself above it all, considering it from this new angle of the powerful. From what Indar had said I had expected that Raymond and Yvette would be middle-aged. But the lady--in black slacks in some shiny material--who came to meet us after the white-jacketed boy had let us in was young, in her late twenties, near my own age. That was the first surprise. The second was that she was barefooted, feet white and beautiful and finely made. I looked at her feet before I considered her face and her blouse, black silk, embroidered round the low-cut collar--expensive stuff, not the sort of goods you could get in our town. Indar said, "This lovely lady is our hostess. Her name is Yvette." He bent over her and appeared to hold her in an embrace. It was a piece of pantomime. She playfully arched her back to receive his embrace, but his cheek barely brushed hers, he never touched her breast, and only the tips of his fingers rested on her back, on the silk blouse. It was a house of the Domain, like Indar's. But all the upholstered furniture had been cleared out of the sitting room and had been replaced by cushions and bolsters and African mats. Two or three reading lamps had been put on the floor, so that parts of the room were in darkness. Yvette said, referring to the furniture, "The President has an exaggerated idea of the needs of Europeans. I've dumped all that velvety stuff in one of the bedrooms." Remembering what Indar had told me, I ignored the irony in her voice, and felt that she was speaking with privilege, the privilege of someone close to the President. A number of people were already there. Indar followed Yvette deeper into the room, and I followed Indar. Indar said, "How's Raymond?" Yvette said, "He's working. He'll look in later." We sat down all three next to a bookcase. Indar lounged against a bolster, a man at ease. I concentrated on the music. As so often when I was with Indar on the Domain, I was prepared only to watch and listen. And this was all new to me. I hadn't been to a Domain party like this. And the atmosphere itself in that room was something I had never experienced before. Two or three couples were dancing; I had visions of women's legs. I had a vision especially of a girl in a green dress who sat on a straight-backed dining chair (one of the house set of twelve). I studied her knees, her legs, her ankles, her shoes. They were not particularly well made legs, but they had an effect on me. All my adult life I had looked for release in the bars of the town. I knew only women who had to be paid for. The other side of the life of passion, of embraces freely given and received, I knew nothing of, and had begun to consider alien, something not for me. And so my satisfactions had only been brothel satisfactions, which hadn't been satisfactions at all. I felt they had taken me further and further away from the true life of the senses and I feared they had made me incapable of that life. I had never been in a room where men and women danced for mutual pleasure, and out of pleasure in one another's company. Trembling expectation was in that girl's heavy legs, the girl in the green dress. It was a new dress, loosely hemmed, not ironed into a crease, still suggesting the material as it had been measured out and bought. Later I saw her dancing, watched the movements of her legs, her shoes; and such a sweetness was released in me that I felt I had recovered a part of myself I had lost. I never looked at the girl's face, and it was easy in the semi-gloom to let that remain unknown. I wanted to sink into the sweetness; I didn't want anything to spoil the mood. And the mood became sweeter. The music that was being played came to an end, and in the wonderfully lit room, blurred circles of light thrown onto the ceiling from the lamps on the floor, people stopped dancing. What next came on went straight to my heart--sad guitars, words, a song, an American girl singing "Barbara Allen." That voice! It needed no music; it hardly needed words. By itself it created the line of the melody; by itself it created a whole world of feeling. It is what people of our background look for in music and singing: feeling. It is what makes us shout "_Wa-wa__! Bravo!" and throw bank notes and gold at the feet of a singer. Listening to that voice, I felt the deepest part of myself awakening, the part that knew loss, homesickness, grief, and longed for love. And in that voice was the promise of a flowering for everyone who listened. I said to Indar, "Who is the singer?" He said, "Joan Baez. She's very famous in the States." "And a millionaire," Yvette said. I was beginning to recognize her irony. It made her appear to be saying something when she had said very little--and she was, after all, playing the record in her house. She was smiling at me, perhaps smiling at what she had said, or perhaps smiling at me as Indar's friend, or smiling because she believed it became her. Her left leg was drawn up; her right leg, bent at the knee, lay flat on the cushion on which she sat, so that her right heel lay almost against her left ankle. Beautiful feet, and their whiteness was wonderful against the black of her slacks. Her provocative posture, her smile--they became part of the mood of the song, too much to contemplate. Indar said, "Salim comes from one of our old coast families. Their history is interesting." Yvette's hand lay white on her right thigh. Indar said, "Let me show you something." He leaned across my legs and reached up to the bookcase. He took out a book, opened it and showed me where I was to read. I held the book down to the floor, to catch the light from the reading lamp, and saw, among a list of names, the names of Yvette and Raymond, acknowledged by the writer of the book as "most generous of hosts" at some recent time in the capital. Yvette continued to smile. No embarrassment or playing it down, though; no irony now. Her name in the book mattered to her. I gave the book back to Indar, looked away from Yvette and him, and returned to the voice. Not all the songs were like "Barbara Allen." Some were modern, about war and injustice and oppression and nuclear destruction. But always in between there were the older, sweeter melodies. These were the ones I waited for, but in the end the voice linked the two kinds of song, linked the maidens and lovers and sad deaths of bygone times with the people of today who were oppressed and about to die. It was make-believe--I never doubted that. You couldn't listen to sweet songs about injustice unless you expected justice and received it much of the time. You couldn't sing songs about the end of the world unless--like the other people in that room, so beautiful with such simple things: African mats on the floor and African hangings on the wall and spears and masks--you felt that the world was going on and you were safe in it. How easy it was, in that room, to make those assumptions! It was different outside, and Mahesh would have scoffed. He had said, "It isn't that there's no right and wrong here. There's no right." But Mahesh felt far away. The aridity of that life, which had also been mine! It was better to pretend, as I could pretend now. It was better to share the companionship of that pretence, to feel that in that room we all lived beautifully and bravely with injustice and imminent death and consoled ourselves with love. Even before the songs ended I felt I had found the kind of life I wanted; I never wanted to be ordinary again. I felt that by some piece of luck I had stumbled on the equivalent of what years before Nazruddin had found right here. It was late when Raymond came in. I had, at Indar's insistence, even danced with Yvette and felt her skin below the silk of her blouse; and when I saw Raymond my thoughts--leaping at this stage of the evening from possibility to possibility--were at first only about the difference in their ages. There must have been thirty years between Yvette and her husband; Raymond was a man in his late fifties. But I felt possibilities fade, felt them as dreams, when I saw the immediate look of concern on Yvette's face--or rather in her eyes, for her smile was still on, a trick of her face; when I saw the security of Raymond's manner, remembered his job and position, and took in the distinction of his appearance. It was the distinction of intelligence and intellectual labours. He looked as though he had just taken off his glasses, and his gentle eyes were attractively tired. He was wearing a long-sleeved safari jacket; and it came to me that the style--long sleeves rather than short--had been suggested to him by Yvette. After that look of concern at her husband, Yvette relaxed again, with her fixed smile. Indar got up and began fetching a dining chair from against the opposite wall. Raymond motioned to us to stay where we were; he rejected the chance of sitting next to Yvette, and when Indar returned with the dining chair, sat on that. Yvette said, without moving, "Would you like a drink, Raymond?" He said, "It will spoil it for me, Evie. I'll be going back to my room in a minute." Raymond's presence in the room had been noted. A young man and a girl had begun to hover around our group. One or two other people came up. There were greetings. Indar said, "I hope we haven't disturbed you." Raymond said, "It made a pleasant background. If I look a little troubled, it is because just now, in that room, I became very dejected. I began to wonder, as I've often wondered, whether the truth ever gets known. The idea isn't new, but there are times when it becomes especially painful. I feel that everything one does is just going to waste." Indar said, "You are talking nonsense, Raymond. Of course it takes time for someone like yourself to be recognized, but it happens in the end. You are not working in a popular field." Yvette said, "You tell him that for me, please." One of the men standing around said, "New discoveries are constanty making us revise our ideas about the past. The truth is always there. It can be got at. The work has to be done, that's all." Raymond said, "Time, the discoverer of truth. I know. It's the classical idea, the religious idea. But there are times when you begin to wonder. Do we really know the history of the Roman Empire? Do we really know what went on during the conquest of Gaul? I was sitting in my room and thinking with sadness about all the things that have gone unrecorded. Do you think we will ever get to know the truth about what has happened in Africa in the last hundred or even fifty years? All the wars, all the rebellions, all the leaders, all the defeats?" There was a silence. We looked at Raymond, who had introduced this element of discussion into our evening. Yet the mood was only like an extension of the mood of the Joan Baez songs. And for a little while, but without the help of music, we contemplated the sadness of the continent. Indar said, "Have you read Muller's article?" Raymond said, "About the Bapende rebellion? He sent me a proof. It's had a great success, I hear." The young man with the girl said, "I hear they're inviting him to Texas to teach for a term." Indar said, "I thought it was a lot of rubbish. Every kind of cliche parading as new wisdom. The Azande, that's a tribal uprising. The Bapende, that's just economic oppression, rubber business. They're to be lumped with the Budja and the Babwa. And you do that by playing down the religious side. Which is what makes the Bapende dust-up so wonderful. It's just the kind of thing that happens when people turn to Africa to make the fast academic buck." Raymond said, "He came to see me. I answered all his questions and showed him all my papers." The young man said, "Muller's a bit of whiz kid, I think." Raymond said, "I liked him." Yvette said, "He came to lunch. As soon as Raymond left the table, he forgot all about the Bapende and said to me, 'Do you want to come out with me?' Just like that. The minute Raymond's back was turned." Raymond smiled. Indar said, "I was telling Salim, Raymond, that you are the only man the President reads." Raymond said, "I don't think he has much time for reading these days." The young man, his girl now close to him, said, "How did you meet him?" "It is a story at once simple and extraordinary," Raymond said. "But I don't think we have time for that now." He looked at Yvette. She said, "I don't think anybody is rushing off anywhere right at this minute." "It was long ago," Raymond said. "In colonial times. I was teaching at a college in the capital. I was doing my historical work. But of course in those days there was no question of publishing. There was the censorship that people pretended didn't exist, in spite of the celebrated decree of 1922. And of course in those days Africa wasn't a subject. But I never made any secret of what I felt or where I stood, and I suppose the word must have got around. One day at the college I was told that an old African woman had come to see me. It was one of the African servants who brought me the message, and he wasn't too impressed by my visitor. "I asked him to bring her to me. She was middle-aged rather than old. She worked as a maid in the big hotel in the capital, and she had come to see me about her son. She belonged to one of the smaller tribes, people with no say in anything, and I suppose she had no one of her own kind to turn to. The boy had left school. He had joined some political club and had done various odd jobs. But he had given up all that. He was doing nothing at all. He was just staying in the house. He didn't go out to see anybody. He suffered from headaches, but he wasn't ill. I thought she was going to ask me to get the boy a job. But no. All she wanted me to do was to see the boy and talk to him. "She impressed me a great deal. Yes, the dignity of that hotel maid was quite remarkable. Another woman would have thought that her son was bewitched, and taken appropriate measures. She, in her simple way, saw that her son's disease had been brought on by his education. That was why she had come to me, the teacher at the college. "I asked her to send the boy to me. He didn't like the idea of his mother talking to me about him, but he came. He was as nervous as a kitten. What made him unusual--I would even say extraordinary--was the quality of his despair. It wasn't just a matter of poverty and the lack of opportunity. It went much deeper. And, indeed, to try to look at the world from his point of view was to begin to get a headache yourself. He couldn't face the world in which his mother, a poor woman of Africa, had endured such humiliation. Nothing could undo that. Nothing could give him a better world. "I said to him, 'I've listened to you, and I know that one day the mood of despair will go and you will want to act. What you mustn't do then is to become involved in politics as they exist. Those clubs and associations are talking shops, debating societies, where Africans posture for Europeans and hope to pass as evolved. They will eat up your passion and destroy your gifts. What I am going to tell you now will sound strange, coming from me. You must join the Defence Force. You won't rise high, but you will learn a real skill. You will learn about weapons and transport, and you will also learn about men. Once you understand what holds the Defence Force together, you will understand what holds the country together. You might say to me, "But isn't it better for me to be a lawyer and be called _ma�e__?" I will say, "No. It is better for you to be a private and call the sergeant sir." This isn't advice I will want to give to anybody else. But I give it to you.' " Raymond had held us all. When he stopped speaking we allowed the silence to last, while we continued to look at him as he sat on the dining chair in his safari jacket, distinguished, his hair combed back, his eyes tired, a bit of a dandy in his way. In a more conversational voice, as though he was commenting on his own story, Raymond said at last, breaking the silence, "He's a truly remarkable man. I don't think we give him enough credit for what he's done. We take it for granted. He's disciplined the army and brought peace to this land of many peoples. It is possible once again to traverse the country from one end to the other--something the colonial power thought it alone had brought about. And what is most remarkable is that it's been done without coercion, and entirely with the consent of the people. You don't see policemen in the streets. You don't see guns. You don't see the army." Indar, sitting next to Yvette, who was still smiling, seemed about to change the position of his legs prior to saying something. But Raymond raised his hand, and Indar didn't move. "And there's the freedom," Raymond said. "There's the remarkable welcome given to every kind of idea from every kind of system. I don't think," he said, addressing Indar directly, as though making up to him for keeping him quiet, "that anyone has even hinted to you that there are certain things you have to say and certain things you mustn't say." Indar said, "We've had an easy ride here." "I don't think it would have occurred to him to try to censor you. He feels that all ideas can be made to serve the cause. You might say that with him there's an absolute hunger for ideas. He uses them all in his own way." Yvette said, "I wish he would change the boys' uniforms. The good old colonial style of short trousers and a long white apron. Or long trousers and a jacket. But not that carnival costume of short trousers and jacket." We all laughed, even Raymond, as though we were glad to stop being solemn. And Yvette's boldness was also like proof of the freedom Raymond had been talking about. Raymond said, "Yvette goes on about the boys' uniforms. But that's the army background, and the mother's hotel background. The mother wore a colonial maid's uniform all her working life. The boys in the Domain have to wear theirs. And it isn't a colonial uniform--that's the point. In fact, everybody nowadays who wears a uniform has to understand that. Everyone in uniform has to feel that he has a personal contract with the President. And try to get the boys out of that uniform. You won't succeed. Yvette has tried. They want to wear that uniform, however absurd it is to our eyes. That's the amazing thing about this man of Africa--this flair, this knowledge of what the people need, and when. "We have all these photographs of him in African costume nowadays. I must confess I was disturbed when they began to appear in such number. I raised the issue with him one day in the capital. I was shattered by the penetration of his answer. He said, 'Five years ago, Raymond, I would have agreed with you. Five years ago our African people, with that cruel humour which is theirs, would have laughed, and that ridicule would have destroyed our country, with its still frail bonds. But times have changed. The people now have peace. They want something else. So they no longer see a photograph of a soldier. They see a photograph of an African. And that isn't a picture of me, Raymond. It is a picture of all Africans.' " This was so like what I felt, that I said, "Yes! None of us in the town liked putting up the old photograph. But it is different seeing the new photographs, especially in the Domain." Raymond permitted this interruption. His right hand was being raised, though, to allow him to go on. And he went on. "I thought I would check this. Just last week, as a matter of fact. I ran into one of our students outside the main building. And just to be provocative, I dropped some remark about the number of the President's photographs. The young man pulled me up quite sharply. So I asked him what he felt when he saw the President's photograph. You will be surprised by what he said to me, that young man, holding himself as erect as any military cadet. 'It is a photograph of the President. But here on the Domain, as a student at the polytechnic, I also consider it a photograph of myself.' The very words! But that's a quality of great leaders--they intuit the needs of their people long before those needs are formulated. It takes an African to rule Africa--the colonial powers never truly understood that. However much the rest of us study Africa, however deep our sympathy, we will remain outsiders." The young man, sitting now on a mat with his girl, asked, "Do you know the symbolism of the serpent on the President's stick? Is it true that there's a fetish in the belly of the human figure on the stick?" Raymond said, "I don't know about that. It is a stick. It is a chief's stick. It is like a mace or a mitre. I don't think we have to fall into the error of looking for African mysteries everywhere." The critical note jarred a little. But Raymond seemed not to notice. "I have recently had occasion to look through all the President's speeches. Now, what an interesting publication that would make! Not the speeches in their entirety, which inevitably deal with many passing issues. But selections. The essential thoughts." Indar said, "Are you working on that? Has he asked you?" Raymond lifted a palm and hunched a shoulder, to say that it was possible, but that he couldn't talk about a matter that was still confidential. "What is interesting about those speeches when read in sequence is their development. There you can see very clearly what I have described as the hunger for ideas. In the beginning the ideas are simple. Unity, the colonial past, the need for peace. Then they become extraordinarily complex and wonderful about Africa, government, the modern world. Such a work, if adequately prepared, might well become the handbook for a true revolution throughout the continent. Always you can catch that quality of the young man's despair which made such an impression on me so long ago. Always you have that feeling that the damage can never perhaps be undone. Always there is that note, for those with the ears to hear it, of the young man grieving for the humiliations of his mother, the hotel maid. He's always remained true to that. I don't think many people know that earlier this year he and his entire government made a pilgrimage to the village of that woman of Africa. Has that been done before? Has any ruler attempted to give sanctity to the bush of Africa? This act of piety is something that brings tears to the eyes. Can you imagine the humiliations of an African hotel maid in colonial times? No amount of piety can make up for that. But piety is all we have to offer." "Or we can forget," Indar said. "We can trample on the past." Raymond said, "That is what most of the leaders of Africa do. They want to build skyscrapers in the bush. This man wants to build a shrine." Music without words had been coming out of the speakers. Now "Barbara Allen" began again, and the words were distracting. Raymond stood up. The man who had been sitting on the mat went to lower the volume. Raymond indicated that he wasn't to bother, but the song went faint. Raymond said, "I would like to be with you. But unfortunately I have to get back to my work. Otherwise I might lose something. I find that the most difficult thing in prose narrative is linking one thing with the other. The link might just be a sentence, or even a word. It sums up what has gone before and prepares one for what is to come. As I was sitting with you I had an idea of a possible solution to a problem that was beginning to appear quite intractable. I must go and make a note. Otherwise I might forget." He began to move away from us. But then he stopped and said, "I don't think it is sufficiently understood how hard it is to write about what has never been written about before. The occasional academic paper on a particular subject, the Bapende rebellion or whatever--that has its own form. The larger narrative is another matter. And that's why I have begun to consider Theodor Mommsen the giant of modern historical writing. Everything that we now discuss about the Roman Republic is only a continuation of Mommsen. The problems, the issues, the very narrative, especially of those extraordinarily troubled years of the later Republic--you might say the German genius discovered it all. Of course, Theodor Mommsen had the comfort of knowing that his subject was a great one. Those of us who work in our particular field have no such assurance. We have no idea of the value posterity will place on the events we attempt to chronicle. We have no idea where the continent is going. We can only carry on." He ended abruptly, turned, and went out of the room, leaving us in silence, looking after where he had disappeared, and only slowly directing our attention to Yvette, now his representative in that room, smiling, acknowledging our regard. After a little Indar said to me, "Do you know Raymond's work?" Of course he knew the answer to that one. But, to give him his opening, I said, "No, I don't know his work." Indar said, "That's the tragedy of the place. The great men of Africa are not known." It was like a formal speech of thanks. And Indar had chosen his words well. He had made us all men and women of Africa; and since we were not Africans the claim gave us a special feeling for ourselves which, so far as I was concerned, was soon heightened by the voice of Joan Baez, turned up again, reminding us sweetly, after the tensions Raymond had thrown among us, of our common bravery and sorrows. Indar was embraced by Yvette when we left. And I was embraced, as the friend. It was delicious to me, as the climax to that evening, to press that body close, soft at this late hour, and to feel the silk of the blouse and the flesh below the silk. There was a moon now--there had been none earlier. It was small and high. The sky was full of heavy clouds, and the moonlight came and went. It was very quiet. We could hear the rapids; they were about a mile away. The rapids in moonlight! I said to Indar, "Let's go to the river." And he was willing. In the wide levelled land of the Domain the new buildings seemed small, and the earth felt immense. The Domain seemed the merest clearing in the forest, the merest clearing in an immensity of bush and river--the world might have been nothing else. Moonlight distorted distances; and the darkness, when it came, seemed to drop down to our heads. I said to Indar, "What do you think of what Raymond said?" "Raymond tells a story well. But a lot of what he says is true. What he says about the President and ideas is certainly true. The President uses them all and somehow makes them work together. He is the great African chief, and he is also the man of the people. He is the modernizer and he is also the African who has rediscovered his African soul. He's conservative, revolutionary, everything. He's going back to the old ways, and he's also the man who's going ahead, the man who's going to make the country a world power by the year 2000. I don't know whether he's done it accidentally or because someone's been telling him what to do. But the mish-mash works because he keeps on changing, unlike the other guys. He is the soldier who decided to become an old-fashioned chief, and he's the chief whose mother was a hotel maid. That makes him everything, and he plays up everything. There isn't anyone in the country who hasn't heard of that hotel maid mother." I said, "They caught me with that pilgrimage to the mother's village. When I read in the paper that it was an unpublicized pilgrimage, I thought of it as just that." "He makes these shrines in the bush, honouring the mother. And at the same time he builds modern Africa. Raymond says he doesn't build skyscrapers. Well, he doesn't do that. He builds these very expensive Domains." "Nazruddin used to own some land here in the old days." "And he sold it for nothing. Are you going to tell me that? That's an African story." "No, Nazruddin sold well. He sold at the height of the boom before independence. He came out one Sunday morning and said, 'But this is only bush.' And he sold." "It could go that way again." The sound of the rapids had grown louder. We had left the new buildings of the Domain behind and were approaching the fishermen's huts, dead in the moonlight. The thin village dogs, pale in the moonlight, their shadows black below them, walked lazily away from us. The fishermen's poles and nets were dark against the broken glitter of the river. And then we were on the old viewing point, repaired now, newly walled; and around us, drowning everything else, was the sound of water over rocks. Clumps of water hyacinths bucked past. The hyacinths were white in the moonlight, the vines dark tangles outlined in black shadow. When the moonlight went, there was nothing to be seen; the world was then only that old sound of tumbling water. I said, "I've never told you why I came here. It wasn't just to get away from the coast or to run that shop. Nazruddin used to tell us wonderful stories of the times he used to have here. That was why I came. I thought I would be able to live my own life, and I thought that in time I would find what Nazruddin found. Then I got stuck. I don't know what I would have done if you hadn't come. If you hadn't come I would never have known about what was going on here, just under my nose." "It's different from what we used to know. To people like us it's very seductive. Europe in Africa, post-colonial Africa. But it isn't Europe or Africa. And it looks different from the inside, I can tell you." "You mean people don't believe in it? They don't believe in what they say and do?" "No one is as crude as that. We believe and don't believe. We believe because that way everything becomes simpler and makes more sense. We don't believe--well, because of this." And Indar waved at the fishermen's village, the bush, the moonlit river. He said after a time, "Raymond's in a bit of a mess. He has to keep on pretending that he is the guide and adviser, to keep himself from knowing that the time is almost here when he will just be receiving orders. In fact, so as not to get orders, he is beginning to anticipate orders. He will go crazy if he has to acknowledge that that's his situation. Oh, he's got a big job now. But he's on the slippery slope. He's been sent away from the capital. The Big Man is going his own way, and he no longer needs Raymond. Everybody knows that, but Raymond thinks they don't. It's a dreadful thing for a man of his age to have to live with." But what Indar was saying didn't make me think of Raymond. I thought of Yvette, all at once brought nearer by this tale of her husband's distress. I went over the pictures I had of her that evening, ran the film over again, so to speak, reconstructing and reinterpreting what I had seen, re-creating that woman, fixing her in the posture that had bewitched me, her white feet together, one leg drawn up, one leg flat and bent, remaking her face, her smile, touching the whole picture with the mood of the Joan Baez songs and all that they had released in me, and adding to it this extra mood of moonlight, the rapids, and the white hyacinths of this great river of Africa.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A bend in the river»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A bend in the river» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A bend in the river» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.