V. Naipaul - Magic Seeds

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «V. Naipaul - Magic Seeds» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2005, ISBN: 2005, Издательство: Vintage, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

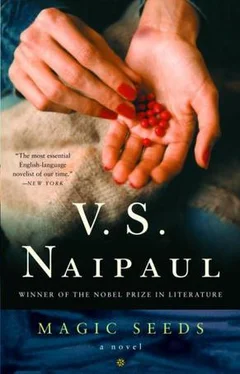

- Название:Magic Seeds

- Автор:

- Издательство:Vintage

- Жанр:

- Год:2005

- ISBN:978-0375707278

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Magic Seeds: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Magic Seeds»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Having left a wife and a livelihood in Africa, Willie is persuaded to return to his native India to join an underground movement on behalf of its oppressed lower castes. Instead he finds himself in the company of dilettantes and psychopaths, relentlessly hunted by police and spurned by the people he means to liberate. But this is only one stop in a quest for authenticity that takes in all the fanaticism and folly of the postmodern era. Moving with dreamlike swiftness from guerrilla encampment to prison cell, from the squalor of rural India to the glut and moral desolation of 1980s London, Magic Seeds is a novel of oracular power, dazzling in its economy and unblinking in its observations.

Magic Seeds — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Magic Seeds», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

For a long way outside the village the lord’s lands could still be seen: overgrown fields, unirrigated and dried up, untended orchards of lemons and sweet limes with long, straggly branches, acacia and neem growing everywhere.

Ramachandra said, “These villagers can make you want to cry. Most of them don’t have land, and for three years at least we’ve been trying to get them to take over these six hundred acres. We’ve held any number of meetings with them. We’ve told them about the wickedness of the rule of the old days. They agree with all of that, but when we tell them that it is up to them now to take over and plough these acres, they say, ‘It’s not our land.’ We will talk for two hours and they will appear to agree with you, but then at the end they will say again, ‘It’s not our land.’ You can get them to clean out water tanks. You can get them to build roads. But you can’t get them to take over land. I begin to see why revolutions have to turn bloody. These people will begin to understand the revolution only when we start killing people. They will have no trouble understanding that. We have started at least three revolutionary committees in this village and in many of the others. They have all faded away. The young men who join us want blood. They have been to high school. Some even have degrees. They want blood, action. They want the world to change. All we give them is talk. That is Kandapalli’s legacy. They see nothing happening and they drop out. If we were ruling the liberated areas with an iron hand, as we should, we would have all those six hundred acres cleared and ploughed in a month. And people would have had some idea of what the revolution means. We have to do something this time. We’ve heard that the family of the old tax-collector is trying to sell this land. They ran away at the time of the first rebellion and they have been living in some city or other ever since. Living in the old parasitic way, doing nothing. Now they are poor. They want to sell this land in some shady deal to a rich local farmer, a kind of Shivdas figure. He lives about twenty miles away. We are determined to prevent this deal. We want the land to be occupied by the villagers, and it looks as though this time we will have to kill some people. I think we will have to leave some people behind here to enforce our will. This is where Kandapalli has been undermining us. Crying for the poor, hardly able to finish a sentence, impressing everybody, and doing nothing.”

They came to the lord’s house. It was two storeys high and the outer wall was blank. The vestibule went through the lower floor of the house. On either side of the vestibule was a high platform two or three feet wide set into an alcove in the thick wall. Here, in the old days, the doormen would have watched or slept or smoked water pipes and simpler visitors would have waited. This style of house — courtyards alternating with suites of rooms with a central passageway, so that it was possible from the front to see down a tunnel of light and shade right through to the back — this style of house would have been an ancient way of building here. Many farmers had simpler versions of the big house. It spoke of a culture that, in this respect at least, was still itself; and Willie, in the foul smell of the half-rotten big house, found himself moved by this unexpected little vision that had been granted him of his country. The past was terrible; it had to be done away with. But the past also had a kind of wholeness that people like Ramachandra couldn’t begin to care about and couldn’t replace.

It was as Ramachandra had prophesied at the village meeting the next evening. They came respectfully in their short turbans and in their loincloths long or short and in their long shirts, and they listened and looked wise. The uniformed men of the movement let their guns be seen, as Ramachandra had ordered. Ramachandra himself looked impatient and hard and tapped his bony fingers on his AK-47.

“There are five hundred or six hundred acres here. A hundred of you could take over five acres each and start ploughing, start bringing it back to fertility.”

They made a kind of collective sigh, as though that was something they longed for. And yet, when Ramachandra questioned people individually, the reply was only, “The land is not ours.”

He said to Willie afterwards, “You see how fine old manners and fine old ways equip people for slavery. It’s the ancient culture our politicians talk about. But there is something else. I understand these people because I am one of them. I just have to pull a little switch in my head and I know exactly what they are feeling. They accept that some people are rich. They don’t mind that at all. Because these rich people are not like them. The people like them are poor, and they are determined that the poor shall remain poor. When I tell them to take ten acres each, do you know what they are thinking? They are thinking, ‘I don’t want Srinivas to get ten acres of land. It will make him intolerable. Better if I don’t get ten acres if it prevents Srinivas and Raghava from getting ten more acres.’ Only the gun can bring revolution. I am thinking that this time we will have to leave half a squad here to bring them to their senses.”

That evening he said to Willie, “I feel we are always taking one step forward and then two steps back, and the government is always there waiting for us to fail. There are some people in the movement who have been in all the rebellions and have spent thirty years doing what we do. They are people who really don’t want anything to happen now. For them revolution and hiding and knocking on villagers’ doors and asking for food and shelter for the night has become a way of life. We have always had our hermits wandering about the forest. It’s in our blood. People applaud us for it, but it’s got us nowhere.”

He was becoming wild, passion overcoming the regard he had for Willie, and Willie was glad when they separated for the night.

Willie thought, “They all want the old ways to go. But the old ways are part of people’s being. If the old ways go people will not know who they are, and these villages, which have their own beauty, will become a jungle.”

They left behind three men of the squad, to talk about the need to plough the lord’s land.

Ramachandra, more philosophical this morning, like a cat that has abruptly forgotten its rage, said, “They won’t do anything.”

A mile out of the village young men began to come out of the forest. They walked in step with the squad. There was no mockery in them.

“Our recruits,” Ramachandra said. “You see. High school boys. As I told you. For them we are a vision of the life they once had. But they didn’t have the money to stay on in the small town they went to for their education. We are for them what the London-returned and America-returned boys were for you. We will let them down, and I feel it is better to let them go at this stage.”

At noon they rested.

Ramachandra said, “I haven’t told you why I joined the movement. The reason is actually very simple. You know about the college boys who befriended me in the town and bought a suit for me. There was a teacher at that college who for some reason was very nice to me. When I got my diploma I thought I should do something in return for him. You know what I thought? Please don’t laugh. I thought I should ask him to dinner. It was something that was always happening in the Mills and Boon books. I asked him whether he would like to have dinner with me. He said yes, and we fixed a date. I didn’t know what to do about that dinner. It tormented me. I had never given anyone dinner. A crazy idea came to me. There was a rich family in the town. They were small industrialists, making pumps and things like that. Dazzling to me. I didn’t know these people, but I took my courage in both hands and went to their big house. I put on my suit, the one that had given me so much joy and pain. You can imagine the cars in the drive, the lights, the big verandah. People were coming and going, and no one noticed me at the beginning. Halfway down the drawing room there was the kind of bar that people in these modern houses have. No one was paying me too much attention, with all the crush, and I felt that I could even sit at the bar and ask the bow-tied servant for a drink. He was the only one I felt I could talk to. I didn’t ask him for a drink. I asked him who the owner of the house was. He pointed him out to me, sitting on an open side verandah with other people. Sitting out in the cool night air. A sturdy rather than plump middle-aged man with thin hair smoothed back. With my heart in my boots, as the saying is, I went to the verandah and said to the great man, in the presence of all the people there, ‘Good evening, sir. I am a student at the college. Professor Coomaraswamy is my teacher, and he has sent me to you with a request. He very much would like to have dinner with you on — I gave the date — if you are free.’ The great man stood up and said, ‘Professor Coomaraswamy is greatly admired in this town, and it would be an honour to have dinner with him.’ I said, ‘Professor Coomaraswamy particularly wants you to host the dinner, sir.’ The Mills and Boon books had given me this language. Without Mills and Boon I couldn’t have done any of it. The great industrialist looked surprised but then said, ‘That would be an even greater honour.’ I said, ‘Thank you, sir,’ and almost ran out of the big house. On the day I put on my suit of pain and joy and took a taxi to my professor’s house. He said, ‘Ramachandra, this really gives me great pleasure. But why have you come in a taxi? Are we going far?’ I didn’t say anything, and we drove to the industrialist’s. My professor said, ‘This is a very grand house, Ramachandra.’ I said, ‘For you, sir, I want nothing but the best.’ I led him to the open verandah, where the industrialist and his wife and some other people were sitting, and then again I almost ran out of the house. The next day in the college my professor said, ‘Why did you kidnap me last night and take me to those people, Ramachandra? I didn’t know who they were, and they didn’t know anything about me.’ I said, ‘I am a poor man, sir. I can’t give someone like you dinner, and I wanted only the best for you.’ He said, ‘But, Ramachandra, my background is like yours. My family were just as poor as you.’ I said, ‘I made a mistake, sir.’ But I was full of shame. That was where that suit and Mills and Boon had taken me. I hated myself. I wanted to wipe out everyone who had witnessed my shame. I imagined the laughter of all those people in the verandah. I felt I couldn’t live in the world unless those people were dead. Unless my professor was dead. I have almost forgotten what they looked like, but that shame and anger is still with me.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Magic Seeds»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Magic Seeds» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Magic Seeds» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.