“So you think they ignore us out of resentment?”

“If you like.”

“I can understand it quite easily,” said the other cousin. “It’s an ancient misunderstanding between our family and the Albanians. They can’t get used to our imperial dimension, or rather they don’t think it’s of any consequence. They care little for what the Quprilis have done and continue to do for the Empire as a whole. All that matters to them is what we’ve done for the small part of the Empire that is Albania. They’ve always expected us to do something specially for them.”

He threw out his arms as if to say, “So there you have it!”

“Some people think Albania is doomed; others think it was born under a lucky star. I think the question’s more complicated than that. Albania is rather like our family—it has experienced both favor and severity at the Sultan’s hands.”

“And which of the two has counted most with them?” asked Kurt.

“Hard to say,” answered the cousin. “I remember what a Jew said to me one day: ‘When the Turks rushed at you brandishing spears and sabers, you Albanians thought they’d come to conquer you, but in fact they were bringing you a whole Empire as a present!’”

Kurt laughed.

The cousin’s dim eyes seemed to emit a last spark.

“But like all madmen’s gifts,” said the other cousin, “it brought with it violence and bloodshed.”

Kurt laughed again, more loudly this time.

“Why do you laugh?” asked his brother, the governor. “The Jew was right. The Turks have shared power with us—you know that as well as I do.”

“Of course,” said Kurt. “Those five prime ministers prove it,”

“That was only the beginning,” said the governor. “After them there were hundreds of senior officials.”

“That wasn’t what I was laughing at,” said Kurt.

“You’re a spoiled brat,” muttered the other.

A glint came into Kurt’s eye.

“The Turks,” went on the cousin, trying to attract attention again, “gave us Albanians what we lacked: the wide open spaces.”

“And wide open complications too,” said Kurt. “It’s bad enough when an individual life gets caught up in the mechanisms of power—when a whole nation is drawn in it’s a million times worse!”

“What do you mean?”

“Weren’t you just saying the Turks shared power with us? Sharing power doesn’t just mean dividing up the carpets and the gold braid. That comes afterward. Above all, sharing power means sharing crimes!”

“Kurt, it’s not right to talk like that!”

“Anyhow, it’s the Turks who helped us to reach our true stature,” said the cousin. “And we just cursed them for it.”

“Not us—them!” said the governor.

“Sorry—yes… Them. The Albanians back home in Albania.”

A tense silence followed. Loke brought in trays of cakes.

“One day they’ll win real independence, but then they’ll lose all those other possibilities,” continued the cousin. “They’ll lose the vast space in which they could fly like the wind, and be shut up in their own small territory. Their wings will be clipped, and they’ll flap clumsily from one mountain to another until they’re exhausted. Then they’ll ask themselves, ‘What did we gain by it?’ And they’ll start looking for what they’ve lost. But will they ever find it?”

The governor’s wife heaved a deep sigh. No one had touched the cakes.

“Anyhow,” said Kurt, “for the moment they don’t say anything about us.”

“One day they’ll understand us,” said the governor.

“We ought to listen to them too.”

“But you just said they don’t say anything.”

“Then we should listen to their silence,” said Kurt.

The governor guffawed.

“Still the same old eccentric!” he laughed. “As I said, life in the capital has spoiled you. It would do you good to spend a year working for the government in some distant province.

“God forbid!” breathed Mark-Alem’s mother.

The governor’s laughter had relieved the tension, and forks were stretched out to spear the cakes.

“I invited the Albanian rhapsodists to come because I wanted to hear the Albanian epic,” said Kurt. “The Austrian ambassador has read parts of it, and he thinks Albanian epics are much finer than the Bosnian ones.”

“Does he indeed?”

“Yes,” said Kurt. He blinked as if blinded by sunlight on snow. “They talk about hunts through the mountains; single combats; the abduction of women and girls; wedding processions to marriages full of danger; khroushks * rooted to the spot with fear lest they’ve made some mistake; horses drunk on wine; knights who’ve been treacherously blinded riding on blinded steeds through mountains holding their breath; owls foretelling woe; knockings at the gates of strange manor houses at night; a macabre challenge to a duel, issued to a dead man by a live one lurking around his grave with a pack of two hundred hounds; the moans of the dead man unable to rise from his grave to fight his enemy; men and gods quarreling, fighting, intermarrying; shrieks, battles, horrible curses; and over all, a cold sun that sheds light but never warms.”

Mark-Alem listened as if bewitched. He was filled with a strange homesickness for the distant winter snow on which he had never trod.

“That’s what it’s like, the Albanian epic from which we are absent,” said Kurt.

“If it’s anything like what you describe, no wonder we’re not in it!” observed one of the cousins. “It sounds more like a melodramatic frenzy!”

“But we are in the Slav epic,” said Kurt.

“Isn’t that enough?” asked the cousin with dull eyes. “You said yourself we’re the only family in Europe and perhaps in the world that’s celebrated in a national epic. Don’t you think that’s sufficient? Do you want us to be celebrated by two nations?”

“You ask if that isn’t enough for me,” said Kurt. “My answer is no!”

The two cousins shook their heads indulgently. His elder brother smiled too.

“You haven’t changed,” he said. “Still the same eccentric.”

“When the rhapsodists come,” said Kurt, “I invite you all to come and hear them. Among other things they’ll sing the old ‘Ballad of the Bridge with Three Arches,’ about the bridge from which our family name derives….”

Mark-Alem was listening openmouthed.

“But they’ll be singing it in the Albanian version,” Kurt went on. “I haven’t said anything about it yet to the Vizier, but I don’t think he’ll object to our putting them up. They’ll have had a long journey—not to mention the trouble of hiding their instruments. But it’s worth it….”

Kurt went on for some time, speaking with passion. He spoke again of the link between their family here and the Balkan epic there, and of the relations between government and art, the evanescent and the eternal, the flesh and the spirit….

His elder brother’s face had clouded over.

“Be that as it may,” he said, “talk about it as much as you like between these four walls, but be careful not to do so anywhere else.”

Silence fell around the table. The last clink of forks against plates only made it more tense.

To lighten the atmosphere the governor turned to Mark-Alem and said in a sprightly tone:

“We haven’t heard anything from you lately, nephew! You seem to be up to your neck in the world of dreams!”

Mark-Alem felt himself blushing again. Everyone’s attention was once more concentrated on him.

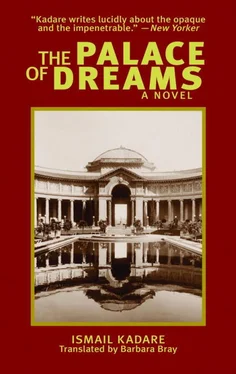

“You work in Selection, don’t you?” his uncle went on. “The Vizier was asking me about you yesterday. A person’s real career in the Palace of Dreams, he said, begins in Interpretation—that’s where the genuinely creative work is done and where people’s individual talents have a chance to shine. Do you agree?”

Читать дальше