Soon she had to give up her position in Galatz and return to Czernowitz. A small swelling of a gland behind her left ear enlarged. My mother brought her to Vienna. We saw her leave, my father and I, in the train station where so many of our arrivals and departures to and from our schools had taken place. My sister, laughing, looked down at us from the window of her compartment, and my father joked boisterously, unconcerned by the reaction of strangers and bystanders, as was his wont when he was in a jolly mood. The train started up slowly, we exchanged some final farewells, we waved good-bye, my father took off his hat and then, turning abruptly, said, “I’ve seen her for the last time.’’

In Vienna, she was treated by a Professor Sternberg. The lymphogranulomatosis, as her affliction was diagnosed, in those days was called “Sternberg’s disease.” But even the efforts of this preeminent authority were of no avail. She wasted away, and soon the tumescence expanded over her neck and down to her shoulder. Once she said to me, “If Father were to see me in this condition, he would help me.” I knew what she meant.

To my mother, she showed great tenderness. She saw how much the poor thing suffered for her. At times, when my mother was sharp with me because of her, our eyes would meet and we couldn’t suppress a smile. Once I caught her unawares as she was observing her mother’s glance sliding off, as happened so often, from the here and now into an indeterminate remoteness. Once again our eyes met, and I understood something unfathomably deep: her expression was hard; she had always feared and hated the threat of slipping away into this indefinite vagueness. Had she realized that this was why she had renounced the poetry of her childhood myth at the Odaya? She gave me a brief nod: it was an admonition.

We became true siblings once more. I left Leoben and stayed in Vienna, where she lay bedridden in our grandmother’s house. I became friends with her kind and gentle Fritz; our close friendship was to last for many years past her death and until his own. Fairly soon it was clear that there was no hope for her. Because she loved the mountains, she was brought to a sanatorium near Hall in the Tyrol, in beautiful surroundings. It bore the somewhat creepy name of Gnadenwald, “Mercywoods’’—an occasion for more of our macabre jokes. She herself had no illusions about her condition. Although her suffering reached almost biblical proportions, she lost none of her courage or her readiness to laugh at absurdity. When I visited her for the last time, she drew me close and whispered, “I must tell you something that will make you laugh. I myself can’t anymore. It hurts too much.” The tumescence had fused her head and shoulders; her hair had fallen out; while receiving radiation, her larynx had inadvertently been burned and now she coughed incessantly; her whole body was covered by an itching rash. What she told me was something that in times past would have united us in laughter.

My mother would not tolerate that any of the sanatorium’s friendly, well-trained personnel took over the care of her daughter. For weeks my sister could not sleep and my mother would keep vigil with her, barely resting between periods of wakefulness. Finally her exhausted child fell asleep, and my mother, almost blinded by fatigue, was about to retire and find some rest herself. But as she stood up, she noticed with horror that a spider was lowering itself on its thread from the ceiling precisely over my sleeping sister’s head. Spiders always had been an abomination for her; there was nothing she found more loathsome. And now here, floating above the face of her deathly sick child, this creature appeared to her as the embodiment of all the evil that had befallen her. Mindless, on blind impulse, she took off her slipper and squashed the spider to the wall with it — with the obvious result that my sister woke up in shock and could not sleep again for weeks.

My sister feasted on my laughing to tears. She whispered that she’d like nothing better than to follow suit — for wasn’t it one of the funniest, most characteristic episodes, typical of her mother’s always misguided good intentions?

A few weeks later we buried her in the cemetery of Hall in the Tyrol.

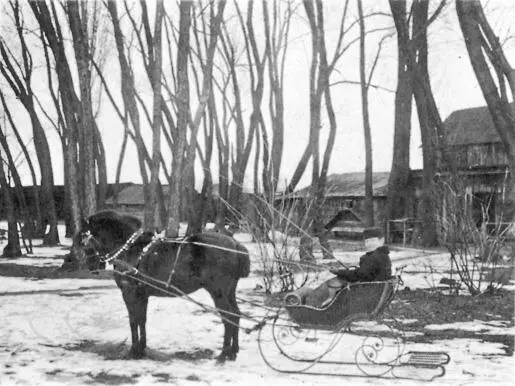

In a cameo set as a brooch, a melancholy faun, sitting under an olive tree, blows on his panpipe; above him are seen the three richly flowing feather panaches of the crest of the Prince of Wales, together with the device Ich dien. The brooch lies in a velvet jewelry box in the lid of which, tipped open, the warrant of arrest for Landru, mass murderer of women, has been pasted. There are ice-flowers on the windows, and some newspapers in cane frames are lying on the marble tabletop of a Viennese coffeehouse. The lady in the back, behind the cash box, wears her short-cropped hair brushed down over her brow and is clad in a wasp-waisted dress; as with “The Lady Without a Lower Half” in a circus sideshow, only her upper trunk can be seen. She holds a magnifying glass in her hand which she discreetly hides whenever someone looks at her .

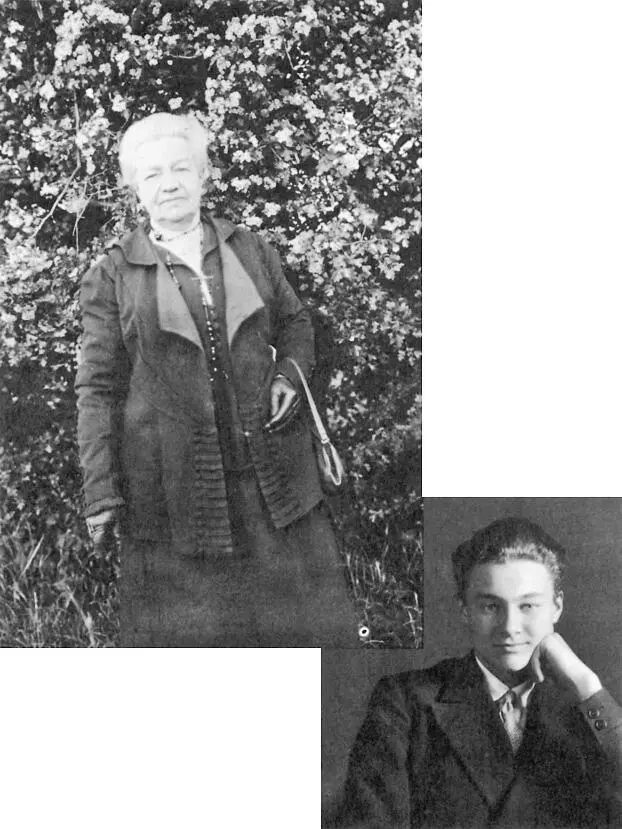

Bunchy came from Stettin, in Pomerania, and stressed this in her typically cheerful, self-assured way, yet at the same time with the ironic pride with which one might speak of one’s chance origin in an exotic place, such as perhaps an island in the West Indies. She had spent her life in many places but not in Stettin; possibly on some West Indian island and a number of years in America. But that she had been born in Pomerania she seemed to consider a special mark that guaranteed a native rural robustness and soundness in body and mind, qualities that Bismarckian Germanness liked to claim as its own. All her life she dressed in the fashion of that period: an imposing figure in the dark, severely waisted, ankle-length dress of the so-called lady companion, with a narrow lace collar closed by an unostentatious pin or brooch. Outdoors she was never seen without gloves of smooth black leather, but she wore no hat during the summer months, so that her hair, snow-white when I knew her, swept upward at the temples, stood up on both sides of the curved brow and dipped in the middle, “like the flame of a gas burner,” as my sister said. Her large face with the short nose and the gruff though often laughing mouth also had something Bismarckian about it, a determination and firmness of character that lent the slanted eyebrows both intelligence and superiority.

She had come to the house of my grandparents in Bohemia, and later to Czernowitz, to serve as the governess of my mother and her siblings, and then, after a decade devoted elsewhere to other pupils, to my sister and me — for all too short a time. She died, almost ninety, in the 1950s in Vienna, closely tied until the end of her days to all three generations of the family — closer, indeed, to each of us than we were to each other.

The only one who kept a reserved distance from her was my father. He also was the only one who addressed her not as Bunchy but as Miss Strauss ( Strauss meaning in German “bunch of flowers’’) and spoke of her as Miss Lina Strauss, suggesting thereby that he could not deny her his respect. She had a solid education and was widely read, had worldly manners, and knew how to keep her place with dignified decency and firmness. He may also have felt that she appreciated his own signal qualities better than others who were misled by his manias and spleens. Whenever he exchanged words with her, it was in observance of a respectful ceremonial, a careful distancing, as in the salute exchanged between two swordsmen. He did not feel the need to show her any additional courtesy. He would ascertain that my sister’s fund of knowledge had gained astoundingly thanks to Bunchy’s instruction, acknowledged that even I was giving signs of domestication under the influence of the “new” governess, before leaving “on assignment.’’

Читать дальше