With the year 1938, political events began to overturn each other in frantic succession. In Vienna I experienced the annexation of Austria by what now had become the Greater German Third Reich, and was surprised when my father commented on it in rather restrained terms in a letter. Wasn’t this the final realization of his youthful political dreams? A German hunting companion who spent those March days in Hermannstadt told me of a rather strange occurrence: everyone of consequence had assembled around the radio in the house of Colonel von Spiess to listen to the news from Vienna. After the triumphal announcement of the consummation of the Ostmark’s “homecoming” to the Reich, the German national anthem was intoned — as is well known, the megalomaniac text by Hofmann von Fallersleben, “Germany, Germany Above All,” that was phonily adapted to Haydn’s melody for the Austrian anthem “God Save Our Emperor.” At the first of these notes, now no longer played in solemnly imperial cadences but blared in marching rhythms, my father made a rejecting gesture and shortly thereafter stood up to take his leave, nervously impatient. He went home. There was no need for an explanation in the house of a former Austrian imperial colonel.

Soon there was hardly any need to explain away my father’s growing skepticism of the Third Reich by his all too well-known affinity for paradox. The invasion of Czechoslovakia occasioned a letter in which he expounded for my benefit on the catastrophic consequences that always ensued whenever the storms of history engulfed Bohemia. It may well be that his unconscious association with Sadowa had incensed his Old Austrian feelings against the obvious Prussianization of the Greater Germany idea, about which he commented in his letters in increasingly testy tones.

Father always considered Prussians as not Germans at all but, rather, Wends and thus Slavs, an unpleasantly assertive minority in the German-speaking world. “Prussia,” he used to say, “is a typical upstart nation: one of the colonies of the Reich that seceded from the mother country and managed to rise to prominence. Similar developments caused the downfall of the Roman Empire. Frederick II of Prussia dealt the death blow to the Holy Roman Empire of Germanic Nations, whose imperial crown legitimately had been worn for six hundred years by Habsburgs. Later Hohenzollerns, foremost William II, extended the damage to catastrophic proportions. A former colony preserves the spirit in which it was founded and administered. The Prussian concept of the state, according to which each citizen is primarily a soldier, should never have impinged on the old dominions of the Reich. But it isn’t merely the calamitous Wilhelminian militarism that is Prussia’s legacy…” and so on.

Whether he considered later developments with an equally consistent perpiscacity and saw in the Third Reich of Hitler (whom he termed a “vagrant housepainter’’) the ultimate debasement of a Prussian pseudo-spirit and thereby the true betrayal of his much beloved concept of a Greater Germany is a moot point. He could not express this in letters; even then, any mail reaching the ever larger realm of Greater Germany from abroad was filtered through a censorship that never would have permitted such heresies to go unpunished. Still, I had many reasons to assume that he was greatly pained by what he saw as a profanation of once pure and stimulating ideas, which were then further perverted by misuse. His quixotic disposition prompted him to translate these convictions into action. When the Transylvanian Saxonians became infected by Third Reich delusions, their leader, a Mr. Roth, managed to extort from the Romanian government, under pressure from the German authorities, the privilege of issuing special passports to German-speaking ethnics in Romania. My father declined such a passport with an expression of thanks. He declared that he was a citizen of the Kingdom of Romania and intended to remain loyal to this allegiance. Unfortunately, the Romanians too no longer had much comprehension for such an attitude. As a result, he remained without a passport. But he had no intention of leaving the country.

The year was 1939 and war had broken out. Russia’s initially peaceful occupation of Bessarabia and the northern Bukovina took place in 1940. The state treaty that made this possible neither surprised nor deceived my father. “Remain where you are,” he wrote to me in Vienna. “One has to go into cover.” He too remained where he was. He still hunted occasionally and cultivated a special friendship with a Princess Sayn-Wittgenstein, born a Nabokova — member of a family with whom I was linked by many independently formed friendships. And then his health began to fail. The irony of fate ordained that the illness that felled him was the one of which my mother imagined herself to be the victim: a kidney ailment. In his case, its origin was clear. While visiting friends, he had contracted scarlet fever from their children. That he survived at all at his age bordered on the miraculous. Without waiting for his complete recovery, he then had jumped into an icy river in the dead of winter to recover a piece of game — he wanted to spare his dog. In September 1943 he took to bed with uremia. It was his wish that I not be informed. Dying is the most private of matters. When he realized he was going blind, he resorted to one of the “strong remedies” from his medicine box in the linen closet.

His friend Bishop Glondys had visited him on the preceding day. To his question whether, after all, there was a message for me, my father replied: “Yes. Please tell him I’m sorry to be dying in a year in which the wine in Transylvania promises to be so outstanding.’’

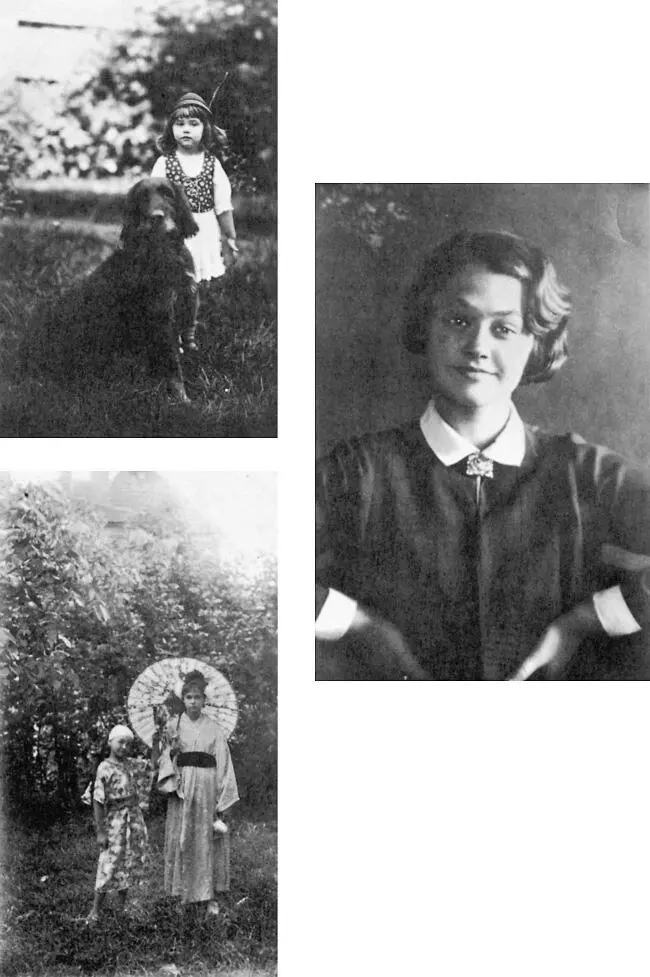

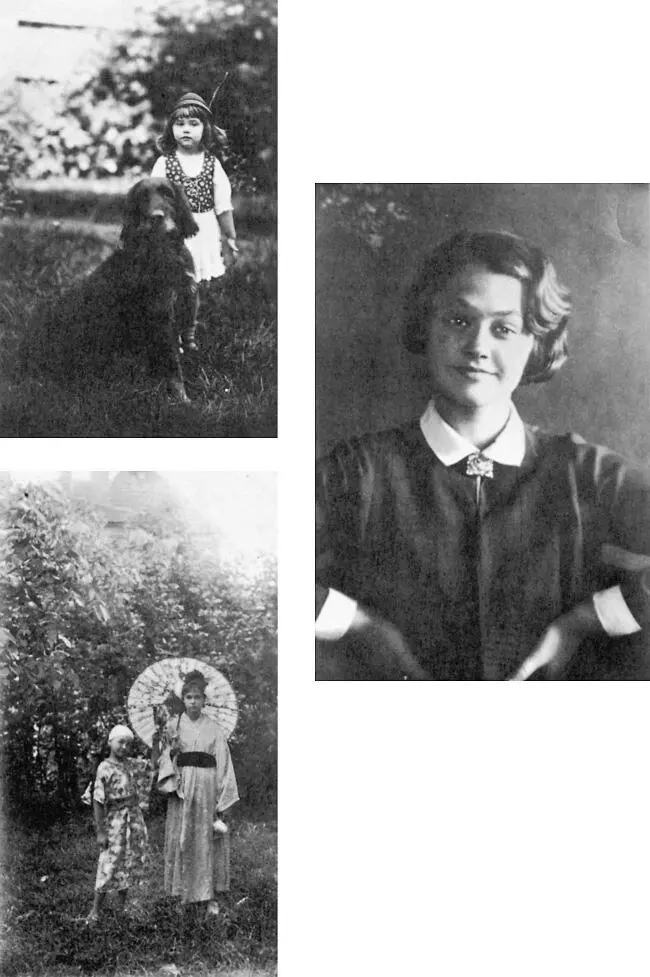

Achild’s paintings on some sheets of paper: large, wondrously dark-shaded flowers, stemless and floating in space as in the world of the blind. Next to it an owl with reading glasses on its round eyes — a sort of student joke, and also a finely chiseled, very pointed stiletto. All this framed by a branchwork of mistletoe twigs in the Art Nouveau style and inscribed with a name, forming an ex libris. The name sounds neo-Romantic, as from a knight’s tale of the turn of the century: Ilse .

Now that I write this down, she has been dead for fifty-six years and not one of those years has gone by without her being close to me in an almost corporeal way — not in the abstract sense of a lovingly preserving memory, but in a well-nigh physical presence, often anything but welcome. Whatever I do or fail to do, whatever happens to me, she stands constantly in front of me, next to me, behind me, observing; at times I even call her to make sure she’s there. For fifty-six years — a whole life span — there has not been for me a single happy or unhappy moment, neither success nor failure, no significant or even halfway noteworthy occurrence on which she might not have commented. She is mute but she is there. My life is a wordless dialogue with her, to which she remains unmoved: I monologize in front of her. In the sequence of images in which I experience myself in life, she is included in every situation, as the watermark in the paper bearing a picture: she has the face of a twenty-year-old, clear eyes watching me with an amused air, one brow raised skeptically, full lips, inherited from her father, ironically angled at the corners. The watchful expression is constant; it is always there.

I would not know where to look in me for the key traumatic experience that generated this obsession, nor do I know how I could find it. With psychoanalytical methods? I don’t quite believe in them. In the 1930s in Vienna, when I still could have consulted the great Sigmund Freud himself, I came across a copy of his case history of the “Wolfman.” I could not imagine how the distraction of this unfortunate man, scion of an assiduously suicidal family, widower after the suicide of his wife as well, a former millionaire whom the Russian Revolution had driven into exile without a cent, saddled with a hysterical and ailing mother who refused to die, himself afflicted with an exemplary checklist of neuroses — I could not imagine how the derangement of this poor devil could be traced to nothing more than that, as an infant, he had accidentally witnessed his parents engaged in coitus a tergo . Even today I find myself unable to deny my skepticism about such allegedly scientific assumptions, especially when I’m supposed also to believe that the discovery itself would induce the healing process (which, incidentally, was not the case with the Wolfman).

Читать дальше