A friend who was with me at the time and who knew nothing of the role she had played in my life, asked in surprise: “Who is this Cro-Magnon female?” “My second mother,” I replied.

Two years later the Russians were in the Bukovina, this time for good, and I never learned what had become of her.

As I recall her now, there is one scene that stands foremost in my mind: a day in winter; it must have been immediately after the end of the First World War and upon our return to the Bukovina after four years of nomadic refugee existence. Cassandra and I are on our way to fetch fresh milk from a neighborhood farmstead. It is surprising that my mother has allowed me to accompany Cassandra, for it is bitterly cold. But fresh milk is a prized rarity and Cassandra has probably taken me along so as to exact compassion — as she had done earlier, during our first flight from the Russians in 1914. The open country into which the large gardens at the edge of town imperceptibly merge lies under heavy snow below which one senses earth in the icy grip of winter. The frost bites so sharply that we are more running than walking. To distract my attention from the cruel cold, Cassandra cuts all kinds of capers, turning us both around, so that we walk a few steps backward, our new tracks now seeming to run parallel to our old ones. Or she makes me hop alongside her, holding me by the hand, first on one foot for a stretch and then on the other, and pointing back she says: “Look, someone with three legs has been walking here!” And then, when I tire, she does something that intuitively I feel is not a spontaneous inspiration but rather the handing down of an age-old lore, a game with which numberless mothers before her in Romania have transformed for their children the agony of the wintry cold into a momentary joy. She places the bottom of the milk can in the snow so that its base rim forms a perfect circle in the smooth white surface; then she sets four similar circles crosswise on both sides and at the top and bottom of the first circle, intersecting it with four thin crescents — lo and behold! a flower miraculously blossoms forth in the snow, an image reduced to its essentials, the glyph of a blossom, such as are seen embroidered on peasant blouses, where these fertility symbols are repeated in endless reiteration to form broad ornamental bands. I too insist on an ornamental reiteration and, struck by this magical appearance, I quite forget the strangling cold. I do not tire of urging Cassandra to embellish our entire path with a border of flowering marks, an adornment of our tracks which I wish all the more to be continuous and without gaps, since I know full well that these tracks will soon be blown away by the wind and covered by the next snow, ultimately to be dissolved entirely in spring with the melting of the snow and thus fated to disappear forever.

Apiece of brocade woven in silver and burgundy lozenges. It may have been part of a harlequin costume that once fitted a female body so tightly as to make it look androgynous, even while accentuating its femininity. I visualize only the body: it has no face. It lies in a treasure chest, the body of a mermaid ensnared in ropes of pearls as if in a net, together with fishes, shells, crabs, starfishes and corals. The mermaid is blind; her world has turned to rubbish. The chest contains the tinsel of a forgotten carnival of long ago. And the mermaid herself is rotting .

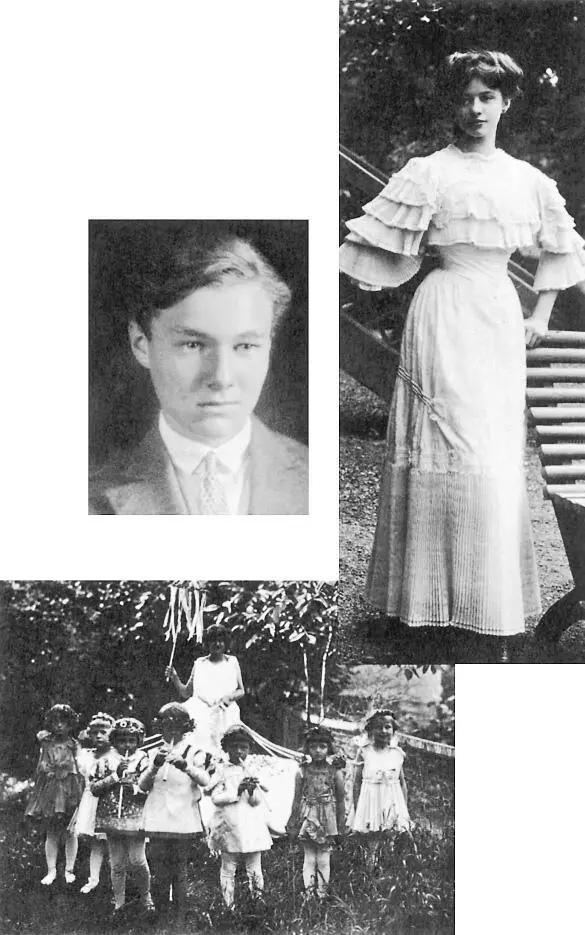

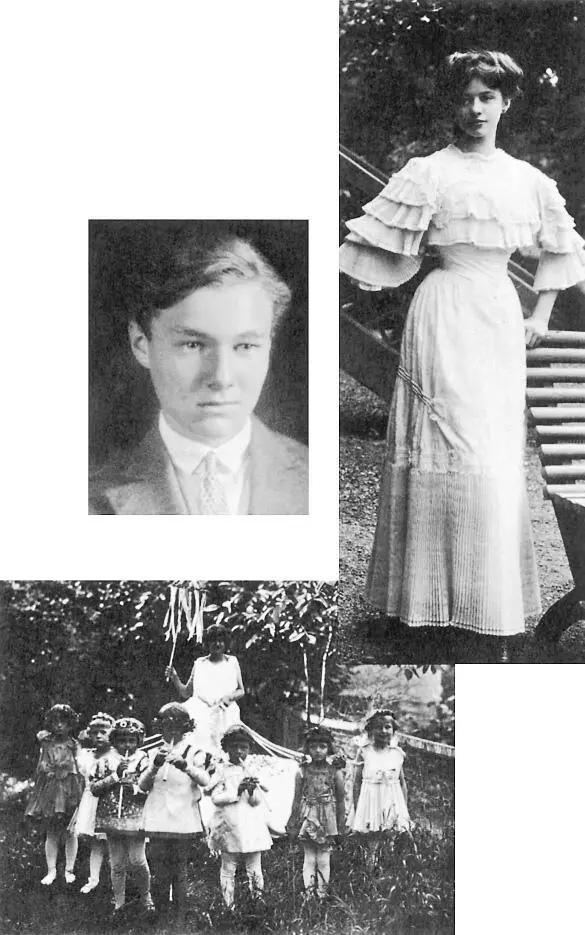

A man who admired her when she was a young bride and then as mother — incidentally, a most artistic, scintillatingly witty man who later was to become my friend and teacher, though unfortunately only for too short a time — this man told me once that it was hard to imagine what subtle fascination had emanated from her when she was relaxed and serene or, even more, when she thought herself unobserved and was lost in thought, enraptured in a transfixed expectancy, an inner-directed listening, awaiting some ineffable occurrence. Only in her last days, when she hoped soon to be rid of the burden of her eighty-six years and longed to be released by death, she recovered some of that shy grace, wafted on her tremulous smile, a dream-bemused question, an expression of bewildered but no longer expectant hearkening. What lay in between was a life of continuous disappointments: an increasingly warped and ever more dreary existence in which anxieties both foolish and legitimate, neuroses both real and imaginary, afflictions, terrors and true obsessions were accompanied by uncontrolled outbreaks of impotent rage that twitched her eyebrows skyward and dimmed her glance as if in frozen panic, senses blunted and mind benumbed, head cowering between hunched-up shoulders, motions jittery and her whole being — now brittle and clumsy and always distraught — shackled in fated abasement. Only the fine facial bone structure and the still full hair which never turned entirely white gave some hint that once she had been beautiful.

Her flowering as a woman was short. The early images of her that I hold in my mind are of great comeliness. It is 1919, the First World War is over and we are back in the Bukovina, where there had been hard-fought battles. Here and there rubble is still rotting in ruined buildings; naked walls and yawning gables rise up to the skies, outlined against indifferently speeding clouds. But some things have remained untarnished. After four years of refugee existence in other people’s houses, my mother is finally mistress of her own home once again. I see her in the light of a summer afternoon ceremoniously putting the last touches to the table set for afternoon tea, arranging cups and flowers. Her face is happy; she dreams of an idealized present, not as it is but as it should and could be. Shortly thereafter she is joined by my father and immediately the atmosphere becomes strained and frosty. The tea is drunk in hostile silence, which torments me because I sense that she is suffering. My sister is unaffected and soon scampers away, luring my father after her into the garden. I too should like to escape to the safety of Cassandra’s hair, but my mother embraces me vehemently, and I love her passionately, love her in a way different from my love of Cassandra. She belongs to that promised land beyond my child’s world; I see in her the embodiment of what one day will be entrusted to me when I too will be a grown man and part of her world: the very essence of frail, vulnerable femininity in need of protection. No doubt my later realization of what toughness and occasional callousness hid behind her apparent delicacy did not favorably influence my subsequent attitude toward women.

Her love for me was stormy. I do not care to call it passionate, for that would presuppose impulses and initiatives, and one failed to find anything in her being that emanated directly from her. She lived not according to any immanent motive but by preconceptions. She loved me as “the mother” should, according to a fixed concept of what mother and child were supposed to be, a fickle love that depended on the submission with which I conformed to my role as child. No other torments of childhood were so painful as the intensity of that love, which constantly required me to give something I was unable to grant. She required more than my goodwill to be a well-mannered child, to grow and to thrive under her care. I felt I was expected not merely to fulfill the stereotype of the perfectly educated, well-bred son, unconditionally loving his mother, but in addition to provide something lacking in herself. In her hands, I was both tool and weapon with which to overcome her emptiness — and perhaps also some anticipatory foreboding of her own destiny, whose fated finality she refused to accept.

Читать дальше